In The Vanishing Stepwells of India, Victoria Lautman articulates how a traditional water conservation system was foolishly destroyed when the British took the reins.

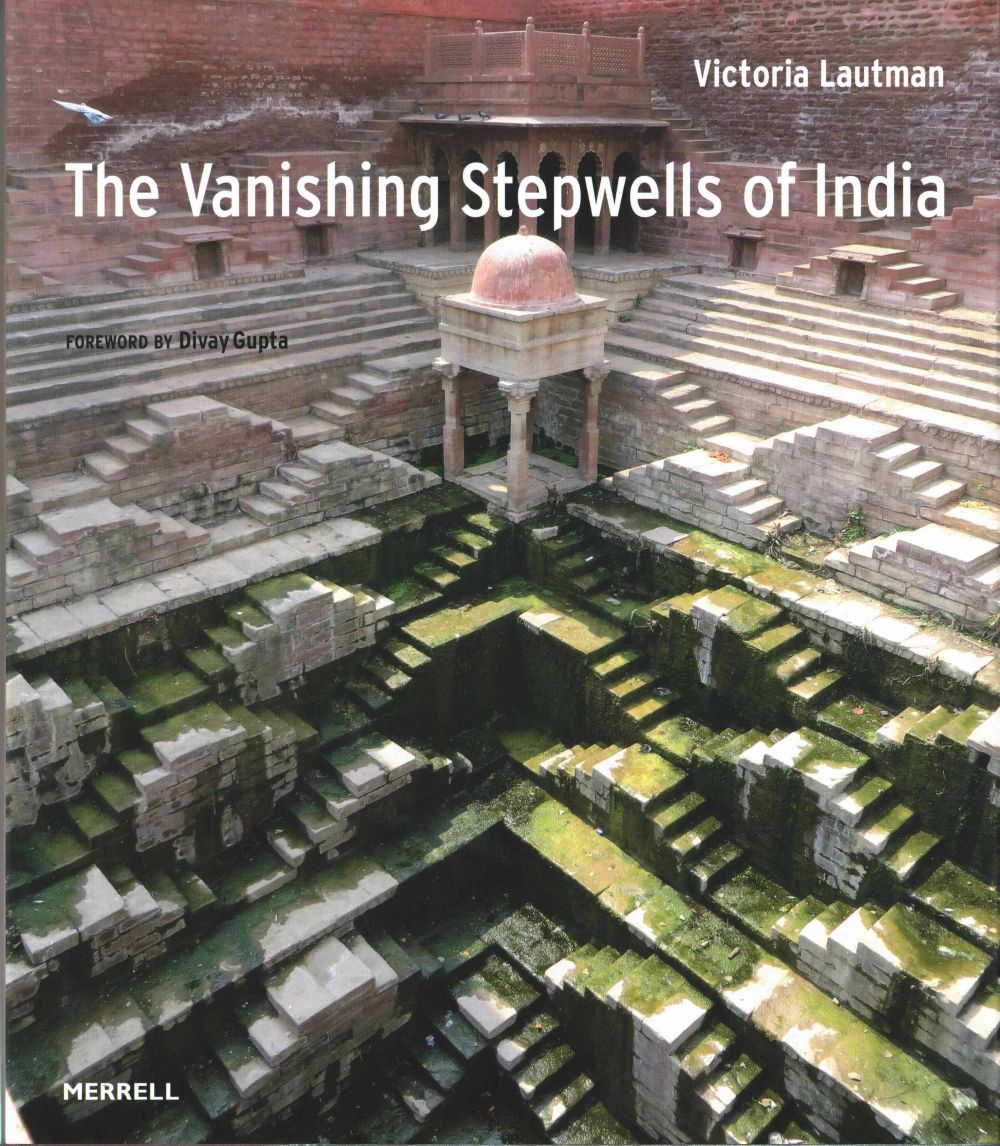

Chand Baori. Credit: The Vanishing Stepwells of India

It is not difficult to comprehend the importance of water conservation. The resource is as precious and far more valuable than gold. Water will always be scarce and in arid, dry regions, the liquid is worshipped. It is an integral element in rituals that manifest faith. All living organisms are dependent on water. The baoli, the bavri, the vav were elaborate ‘fortresses’ that were constructed to protect this precious resource.

Traditionally, myth and legend, faith and worship in the sub-continent respected nature and saw her as a divine force. The vehicles of the multiple representations of gods and goddesses lived in the forest – Durga and the tiger; Kartikeya and the peacock; Bhairav guarding Banaras with his dog. Plants too were linked to the divine – Shiva and the dhatura as one example. Rivers were sacred. Every habitation had a community water tank, often built at the site of a temple, and a village well. The sun, moon and planets were worshipped in the belief that their movements in the universe determined the fate of individuals, families and the community. Conservation was inherent in the cultural stream of India, it was once a way of life. It was in this frame of life and living that stepwells were conceived and built.

Evidence of water reservoirs and tanks are found in the historic sites of the Indus Valley, Dholavira, Mohenjodaro, Dhank and more. The first stepwells cut into underlying rock date back to 200-400 AD. From that period on, through the ages, up until the time of the great Mughal emperors of Hindustan – who did not intervene in the tried and tested stepwell culture, as it were. They constructed new ones and protected the ones they had inherited. Stepwells were seen as the lifeline for travelers from distant places who paused and rested in these community ‘sarais’. From the ground surface, geometric patterned steps led down to the water source, scattered with covered pavilions en route at different levels, dotted with shrines for worship.

These bavri’s, baolis and vavs, as they were christened in different parts of India, became public spaces where the community too could congregate, shaded from the hot summer sun that scalded the western and northern tracts of India for nine months in the year. And, as Victoria Lautman has articulated in her book that is deliciously peppered with wonderful pictures of these monumental treasures, stepwells in India were consciously allowed to slip away from being what they once were, and a fine, traditional water conservation system was foolishly destroyed when the British took the reins and ruled India.

The colonisers from a completely alien cultural tradition – disconnected with a carefully calibrated design for living in India – believed that stepwells were a fertile breeding ground for all manner of water-borne diseases and, therefore, filled as many as they could with Earth and virtually shut them down. Others fell into decay as people were encouraged not to use them. The extraordinary baolis of India ceased to be. These traditional sarais where people met were replaced by 20th century rest houses, sterile, isolated and nuclear by definition, unrelated to the village or town and its inhabitants. The texture of living patterns was changing, all of which was alien for the local communities. An uncomfortable layer of convention was superimposed.

The book introduces the very unusual idea of the stepwell, how they were constructed with steps leading down, under the ground, to a water source and is an elaborate compendium of photographs, location and condition of the stepwells she has visited across Gujarat, Rajasthan and Delhi. It brings into focus the need to restore and conserve these architectural gems that served as serais, where travelers rested, where people beat the heat during the long summer months by descending into the subterranean to keep cool – and they remained critical water sources when in use. She also shows how neglect and disrespect for these ‘reservoirs’ have amputated an essential element of life and living in areas where water was scarce. The Vanishing Stepwells of India is a must-have illustrated directory of some of the finest stepwells in India.

Now, seven decades after independence, there is a serious attempt to restore and reinvent the great stepwells of India – particularly in Rajasthan. New techniques need to be introduced into the restored bavris, baolis and vavs to conserve water and community conversations. Lautman has been a pioneer in the listing of these step-wells as she traversed some parts of Gujarat, Rajasthan and Delhi, and the book is a great reference manual that needs to be extended further drawing in more information. It is a ‘must have’ book. In Rajasthan, for example, listings are underway, to be presented with attached technical briefs about the present condition of these elaborate, often intricately carved, structures, to local collectorates in an effort to begin a revival and rejuvenation of the stepwells of Rajasthan. A return to tried and tested systems in an environment that can be harsh and difficult for many months, could be one of the solutions necessary to bring back into play, the dignity of water.

Malvika Singh is a Delhi-based writer and editor