Indian Agriculture's Enduring Question: Just How Many Farmers Does the Country Have?

In a speech last September, Prime Minister Narendra Modi noted that 85% of India’s farmers own small tracts of land.

The timing of the address was crucial. Modi was defending the new controversial farm laws and trying to make a larger point on why collective contract farming – which one of the three laws seek to allow – would be beneficial for India’s farmers.

But, if one was ever able to ask the Prime Minister the absolute number of farmers that the 85% he mentioned would translate to, you would be lucky to get a response. This is because the Indian government doesn’t quite know how many farmers there are in India, or indeed, who really is a farmer.

In fact, last month, the Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers’ Welfare was asked in parliament this very pointed question: 'How many farmers there are in India?' The minister, Narendra Tomar, responded not by providing the number of farmers but by providing data for the number of operational landholdings in the country.

Also read: How Diversifying Public Procurement of Grains Can Resolve the Impasse Over MSP

That is also what Modi was referring to when he spoke about 85% of farmers owning small tracts of land. Both Modi and Tomar were providing data that the government of India often provides when it is asked for the number of farmers in the country – data on the number of operational landholdings, that is the number of farms.

The operational landholdings data comes from the Agriculture Census of India of 2015-16 and it does not provide the number of farmers in the country. It is a proxy – at best – for the number of farmers in India. It provides the total number of landholdings in the country, that is the number of farms and not farmers.

The number of farmers could be higher or lower, although most experts believe the former is more likely.

“It might be more common in most parts to have more farmers than holdings,” says economist Sudha Narayanan, who is writing a paper on this very subject. Narayanan is an associate professor of economics at the Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research (IGIDR) and specialises in agriculture economics.

Representational image. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

The agricultural census is not the only source of an estimate – or proxy – for the number of farmers in India. There are several. Different government departments and statistical organisations provide figures that vary quite a lot.

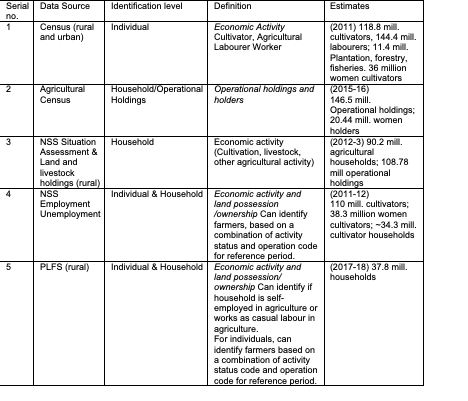

In their upcoming paper, Narayanan and Shree Saha, who is a PhD candidate at Cornell University, provide a table that gives a snapshot of the different estimates of the number of farmers according to different arms of the government of India. There are as many as five different estimates and none of them provide a good answer to the question ‘how many farmers there are in India’.

How various government estimates try to capture the number of farmers in the country. Credit: Narayanan and Saha.

In fact, they don't even agree on who is a 'farmer'. Some seek to define those engaged in farming based on whether it is their main (what ‘main’ means is also different in different estimates) source of income, while some focus on whether agricultural land is owned. Some take both into account.

Some seek to ascertain the number of individual farmers. Others want to know how many farming households there may be in India. One (the population census) is a complete population count exercise while the others are sample surveys.

So, the first problem that needs to be addressed is to define who a farmer is. This is particularly important now as income support schemes gain currency and problems will emerge if a database of beneficiaries does not exist. That problem has already emerged under the hastily announced and implemented PM Kisan scheme, but more on that a little later.

The National Commission on farmers set up in 2004 under M.S. Swaminathan sought to address the question of defining farmers. According to Narayanan and Saha’s paper that definition is “very broad and inclusive” as it did not seek to define a farmer based on ownership of land alone and paved the way for a tiller or cultivator to be classified as a farmer too.

It also allowed for women to be characterised as farmers, something they continue to be deprived of as it is male members overwhelmingly who are landowners.

“For the purpose of this Policy, the term ‘FARMER’ will refer to a person actively engaged in the economic and/or livelihood activity of growing crops and producing other primary agricultural commodities and will include all agricultural operational holders, cultivators, agricultural labourers, sharecroppers, tenants, poultry and livestock rearers, fishers, beekeepers, gardeners, pastoralists, non-corporate planters and planting labourers, as well as persons engaged in various farming related occupations such as sericulture, vermiculture and agro-forestry. The term will also include tribal families / persons engaged in shifting cultivation and in the collection, use and sale of minor and non-timber forest produce.” - Definition of a farmer as per the 2007 Swaminathan Commission on farmers.

Adoption of this definition would enable government policy to focus on the person practising farming rather than the land which is being farmed, as the current definitions overwhelmingly focus on. But, adoption has not happened 14 years after the Swaminathan report was submitted to the central government.

Why is this important?

How a farmer is defined in government papers has very practical implications. It determines who benefits from government schemes, and who does not.

For instance, availing a loan under the Kisan Credit Card (KCC), in practise, requires land ownership title. That financial inclusion under KCC remains sub-par despite this, is another story. Those without a clear land title are excluded from the Pradahan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana (PMFBY) too as it requires farmers to possess a KCC account.

So, tenant farmers who are responsible for the sowing and the harvest, and the associated costs, do not have access to the KCC loans, that are supposed to serve crop loans – or working capital loans – and the PMFBY, which is supposed to be an insurance against crop loss. On the other hand, landowners who may not be doing the actual cultivating get the benefits.

All this while the impact on women farmers is disproportionately worse. As many as 73.2% of women in rural India are engaged in agriculture, but women own only 12.8% of the total agricultural land holdings.

Representational image. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

Another flagship Central government scheme where those who do not own land are left out is the PM Kisan scheme. This is crucial because the policy direction appears to be moving in the direction of more income support schemes.

The scheme was launched just a couple of months prior to the Lok Sabha polls of 2019 with retrospective effect so that one instalment could be transferred before polling. Under it, each ‘farmer family’ that owned less than two hectares of land was to be provided income support of Rs 6,000 per year.

Also read: India's Farm Protests: A Basic Guide to the Issues at Stake

As the Centre did not have a database for the number of ‘farmer families’ in the country, it once again relied on the agriculture census of 2015-16. That census, as you would remember, does not provide data for the number of farmers or farmer families. Instead, it provides data for the number of farms, or operational landholdings in the country.

So the Centre initially estimated that 12.5 crore farmer families would benefit from the scheme and that it would cost the taxpayer Rs 75,000 crore. After reelection in May 2019, Modi’s government decided to expand the ambit of the scheme to include all farmers in the country. That meant that all 14.5 crore farmer families in the country, or more precisely 14.5 crore farms in the country would be eligible to receive the Rs 6,000 a year under PM Kisan.

One would think that given the increase in the number of beneficiaries, the total amount allocated for the scheme would also increase proportionately. But, that did not happen.

In fact, the government quickly realised that it won't even be able to spend the amount that had been initially allocated. For the benefit of the scheme to reach 14.5 crore farmer families, as the government claimed it would, it needed to spend Rs 87,000 crore in a year.

In reality, in 2019-20, which was the first full year of the implementation of the scheme, the Centre only spent Rs 48,714 crore reaching around 8 crore farmers. In the next year, it spent around Rs 65,000 crore and the allocation for PM Kisan has now been reduced to that amount. That means the government has allocated only enough to benefit 10.83 crore farmers and not 14.5 crore.

To put this into context, the extension of the scheme to ‘all farmers’ should have meant that the original Rs 75,000 crore allocation increased to Rs 87,000 crore as per the agriculture census database which the government was using. Instead, the allocation has been reduced by 13%.

Some of the responsibility for this, according to the ministry of agriculture, has to lie with states as they have been slow in providing the database to the Centre. West Bengal has refused to participate in the scheme altogether.

The chief reason for the curtailed spending, however, is the lack of a database for farmers. “We went in blind into PM Kisan with no idea who the beneficiary is,” a senior official at the ministry of agriculture and farmers’ welfare said.

The problems with using operational landholding data to transfer amounts to beneficiaries who are individuals and not pieces of land have emerged under PM Kisan. Narayanan explains that the number of actual beneficiaries could be more in some states and less in some states than the number of landholdings.

“If there are siblings in separate households with both names on the patta that they jointly farm, you would have 2 farmers and 1 holding. If the siblings live in a joint family, both names are on the patta, but they have informally demarcated land into two and each farms it independently of the other - they would be counted as 2 holdings and one farmer. So both are possible,” she says and adds, “In general, it might be more common in most parts to have more farmers than holdings.”

Something similar was said by an agriculture ministry official speaking to Down to Earth magazine. “The database on the total number of farmers is poor. On one hand, landless farmers are excluded from the scheme and on the other hand, the number of such families could be more than what the records for operational landholdings show.”

Most states have, so far, fewer farmers registered under PM Kisan than the number of landholdings in their states. “The process is not finished yet. More farmers are registering,” the agriculture ministry official we spoke to said.

But, some states have registered more farmers than the number of landholdings in their state. For instance, from Punjab more than twice the number of farmers than the number of farms in the state have registered under PM Kisan. Gujarat has registered 6 lakh more farmers than the number of landholdings, while Uttar Pradesh has registered more than 5 lakh more.

Mizoram and Manipur have more than three times the number of farmers than landholdings, as per the PM Kisan database.

Explaining the unique problems with the northeastern parts of the country, the ministry official speaking to Down to Earth said, “Another issue, specifically in the north-eastern states, is that they have common property resources and the farmlands are owned by a community rather than one person. So, individual records are not maintained. Also, states have to take up the initiative of mobilising the farmers for registering with the scheme.”

Yet another problem that has plagued PM Kisan is that of amounts being transferred to ‘ineligible beneficiaries’. This problem is also, at least partly, a consequence of the lack of a database of farmers.

The Centre told Parliament last month that 32.91 lakh people who were not entitled, as per the PM Kisan guidelines, to be beneficiaries under the scheme ended up receiving the benefit. That is more than 3% of the total beneficiaries registered under the scheme.

Some of the ineligible beneficiaries were those who were ‘income tax payees’ and were thus ineligible for PM Kisan. These were discovered when the PM Kisan database was linked with the income tax database. While some others were registered under the PM Kisan scheme when the computers of agriculture department officials were hacked.

“Certainly, if the database of farmers was created first and the scheme was launched only after that, many of these problems would not have happened. But that would have taken time,” the ministry official who spoke to us said.

This article went live on March ninth, two thousand twenty one, at zero minutes past seven in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.