India’s Food Problem Is Stewardship, Not Scarcity

On September 29, the world observes the International Day of Awareness of Food Loss and Waste – a reminder that food security is not just about how much we grow, but how much we save. For India, this message is particularly urgent. We are a food-surplus nation, producing record quantities of grains, fruits and vegetables each year. Yet millions of Indians still cannot access a nutritious diet, and the country consistently ranks poorly on the Global Hunger Index.

The paradox of overflowing granaries alongside empty stomachs is not a story of inadequate production. It is a story of losses and leakages in the food system, where crops are squandered in fields, along roadsides, and in warehouses before they reach a plate. We now grow enough to feed our population, but much of this food never reaches the people who need it most. Globally, discussions around food often focus on consumer-level waste: oversized portions, half-eaten plates in restaurants and homes, or discarded supermarket produce. In India, the more urgent challenge lies in food loss—the silent leakage that occurs during harvesting, storage, transportation, and distribution. Estimates suggest that India wastes nearly 68 million tonnes of food annually, with 35–40% of fruits and vegetables lost post-harvest. For farmers, this translates into collapsing incomes even in years of good harvest; for consumers, it drives higher prices, volatile supplies, and compromised nutrition. This difference between “loss” and “waste” is crucial: policy interventions that focus solely on urban consumer behaviour will miss the heart of the problem.

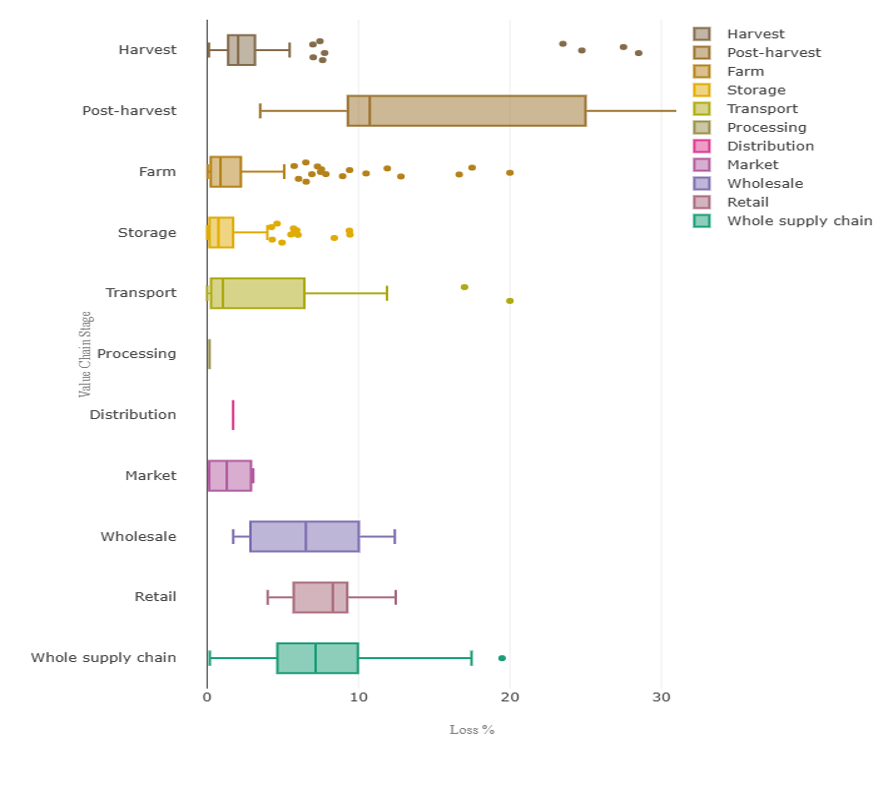

Percentage of food loss in India across different stages of the supply chain. Source: Food and Agriculture Organisation

Food loss is not only an economic tragedy, it is also an environmental one. Agriculture already consumes 80–90% of India’s freshwater, and when food is lost, the water, fertiliser, energy, and land that went into producing it are also wasted. Rotting food further contributes to greenhouse gas emissions. Decomposing organic matter in landfills releases methane, a gas 28 times more potent than carbon dioxide. Globally, food waste is estimated to account for 6–8% of total emissions. For India, where climate stress already affects harvests, this is a double burden: wasted food both deepens hunger and worsens climate change.

The challenge is further aggravated by climate variability. Erratic rains, unseasonal heatwaves, and sudden floods accelerate spoilage. Crops that could once be stored for weeks now decay in days under higher temperatures. Perishables such as apples, tomatoes, and milk face acute losses in the absence of reliable cold chains, turning climate stress into economic disaster. Farmers often confront a cruel choice: distress-sell at throwaway prices or let produce rot, both outcomes feeding the vicious cycle of rural poverty. Indian storage and transport systems, designed for a stable climate and grain-heavy diets, have failed to adapt to changing weather patterns and dietary diversification. Unlike developed countries where cold chains are climate-controlled and insulated, Indian infrastructure remains vulnerable to power outages, poor insulation, and heavy rains. Climate stress, therefore, does not just add to food loss but it exposes the fragility of an agricultural system stuck in the past.

India’s infrastructure deficit lies at the heart of its food loss crisis. Cold storage facilities are concentrated in a handful of states and disproportionately geared toward potatoes, which account for nearly 70% of total capacity. This skew is historical and structural. Potatoes dominate cold storage because they are easy to store, in steady demand, and require simpler technology, leaving perishable fruits and vegetables at risk. Policy incentives have been generic, leaving entrepreneurs to gravitate toward low-risk commodities, exposing high-value perishables to massive losses. Processing capacity is similarly low: only about 10% of perishable produce is processed, compared to 60–70% in countries like the US and Brazil. Weak rural logistics – poor roads, unreliable electricity, fragmented mandi systems – slow down the journey from farm to market. Even public procurement and storage systems lag behind. The Food Corporation of India still relies on archaic godown methods, resulting in substantial grain losses. These inefficiencies not only waste food but also erode farmer incomes, discourage diversification into high-value crops, and reduce consumer access to affordable, nutritious diets.

The consequences of food loss are felt unevenly by different sections of the Indian society. Farmers lose livelihoods when perishable crops rot, while consumers, particularly the poor, pay higher prices for nutritious food. At the same time, urban affluence presents a contrasting picture: extravagant weddings, hotels, and restaurants where food is wasted in abundance. This dual reality reflects India’s social inequality: the farmer who cannot sell tomatoes for ₹2 a kilo is often the same farmer who cannot afford vegetables in the city market, while wealthier consumers normalize excess as a display of prosperity.

Government over the years has launched several initiatives such as Mega Food Parks, cold chain development schemes, and the electronic National Agriculture Market (eNAM) to strengthen infrastructure and markets. There has been some success in reducing grain leakages from the PDS through digitization. But progress has been uneven, highlighting a gap between policy and praxis. Mega Food Parks, while ambitious, have underperformed due to their capital-intensive design, lengthy land acquisition processes, and siting far from farm clusters. Even operational parks run at a fraction of their designed capacity because feeder infrastructure comprising cold chains and transport remains underdeveloped. Municipal food waste segregation continues to be sluggish, so urban waste largely ends up in mixed landfills.

There is a ray of hope in civil society and private initiatives. NGOs such as the Robin Hood Army redistribute surplus cooked food to the needy. Start-ups are experimenting with AI and blockchain-based supply chain solutions to optimise cold storage and reduce spoilage. Farmer Producer Organisations (FPOs) are aggregating produce to improve bargaining power and storage access.

India cannot afford to treat food loss as collateral damage in its agricultural system. Tackling it requires a multi-pronged strategy: expanding decentralised, cold storage and packhouses at the village and FPO level; strengthening market integration through platforms like eNAM to reduce delays and improve price discovery. A processing revolution is also long overdue which needs to start by incentivising small- and medium-scale processing units that extend shelf life and create rural employment; adapting storage and processing solutions to rising temperatures and erratic rainfall; and building robust redistribution networks involving governments, NGOs, and private players to channel surplus food to those who need it most.

Reducing food loss is not just about saving crops – it is about saving water, land, energy and livelihoods. Every kilo of food lost represents wasted resources and unnecessary greenhouse gas emissions. The United Nations has identified halving food loss and waste as a key Sustainable Development Goal (SDG 12.3). On Food Loss and Waste Awareness Day, India must confront its paradox head-on. Our food problem is not scarcity but stewardship. We are a nation of plenty, but unless we plug the leaks in our supply chain, plenty will continue to coexist with poverty. Fixing food loss is not only a moral imperative in a country with widespread hunger, it is also the most practical pathway to achieving food security, farmer and consumer welfare, and sustainability.

Dr Taniya Sah is an assistant professor of Economics at Vidyashilp University, Bengaluru. All views expressed are personal.

This article went live on September twenty-ninth, two thousand twenty five, at fifty-seven minutes past eleven in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.