Interview | In Search of Forgotten Rice: The Experience of Bengal

A rice conservator credited with conserving 400 traditional varieties of rice over his three-decades-long career, Anupam Paul states that these indigenous rice species are hardy and more suited to a changing climate.

Since the 1970s, India has lost more than a lakh varieties of traditional rice varieties that were consumed before the Green Revolution. With the government subsidising a few high-yielding varieties that provided abundant grains on applying chemical fertilisers, the promotion of monoculture caused a massive loss of species and crop diversity. India’s traditional rice varieties are those landraces that have adapted to local climatic and ecological conditions and are cultivated and multiplied by farmers for at least the last half a century. Ninety percent of these varieties are estimated to be lost.

Anupam Paul, a passionate seed conservator, who retired as the Additional Director of Agriculture in the Nadia-based Agricultural Training Centre, Bengal government, is credited with conserving more than 400 varieties of traditional rice seeds.

In an interview with Anumeha Yadav, Paul stated that as the impacts of climate change make temperatures and rainfall more erratic, and lead to breeding new pests and diseases, chemically grown varieties will be particularly vulnerable to fungi attacks or reduced efficacy of pesticides, making the remaining traditional varieties of rice a precious genetic and cultural inheritance to protect:

How did you first start focusing on conserving the traditional rice varieties?

I retired from the Directorate of Agriculture, West Bengal as the Additional Director of Agriculture (Personnel) in February 2023, after working in the government for 31 years. While I was still in government service, I worked on folk rice collection, conservation, popularization and organic farming in the Biodiversity Conservation Farm of Agricultural Training Centre, in Fulia, in Nadia district under the Directorate of Agriculture in eastern Bengal for 20 years. Over the years, I collected more than 400 folk rice varieties from across India.

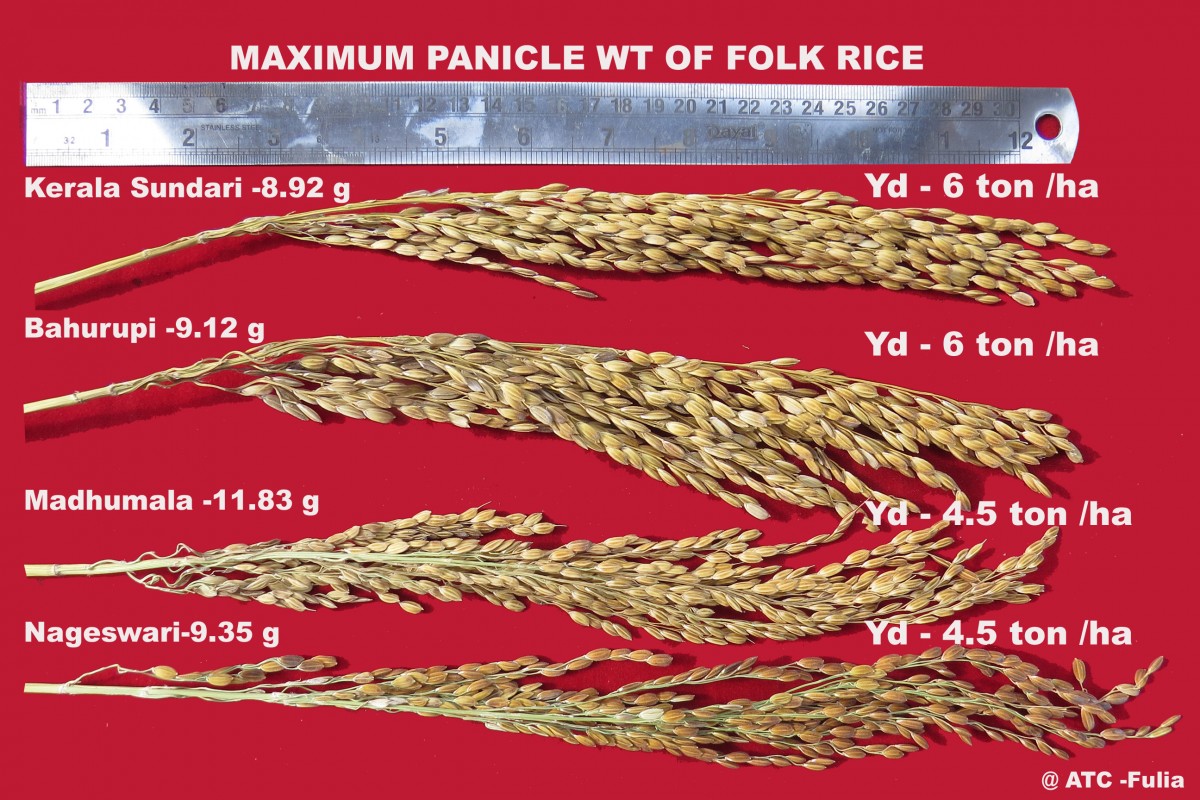

In 2014-15, a scheme named Rastriya Krishi Vikas Yojona(RKVY) on indigenous or folk rice varieties’ collection, conservation, popularization and value addition was implemented for five years in Bengal, first in 11 districts then expanded to 16 districts. This was a unique venture. The agriculture department demonstrated the amazing potential of Desi High Yielding folk rice varieties that can compete with the modern varieties to farmers. We showed that indigenous rice varieties, such as the Kerala Sundari, Bahurupi, can give a good yield of six tonnes per hectare when cultivated under organic mode. It was the first of such attempts.

Traditional rice panicles. Photo: Anupam Paul.

There are now more than 40 farmers’ groups, each with 20 to 30 farmer families and numerous individual farmers in various districts who have re-adopted folk rice replacing modern varieties under chemical mode and its cost of cultivation is less than modern varieties. It is nutritious and tasty. Now, more than 400 folk rice varieties are being cultivated in selected farmers’ fields across Bengal; some farmers are cultivating five to six folk varieties in large areas for commercial purposes, such as Bahurup, Govindbhog, Kalabhat, Baspur rice varieties.

Mainstream agricultural courses in our universities teach chemical farming and during my study I was trained in the same. In 2000, while working as an agriculture officer, I happened to read a book in Bengali called Loot Hoye Jai Swadeshbhumi (‘My Homeland is Plundered’) by plant scientist Debal Deb, who now runs one of the largest seeds bank in Asia conserving more than 1,400 traditional rice varieties varieties in Odisha. This book was about food politics, how yield potentialities of folk rice have been suppressed, a story of our society ignoring the nutrition of folk rice, and the total crop productivity of our rice ecosystem. Deb’s book revealed a different story from what I had known so far.

Could you trace and explain how the Green Revolution affected cultivation in India?

The Green Revolution was launched in the 1960s under the perceived threat of shortages, famine, and to feed the increasing population and it was based on promoting primarily monoculture of rice and wheat. During this so-called Green Revolution, our vast traditional area of rain-fed farming in drought prone areas growing ecologically more suitable cereals such as millet and traditional maize were ignored. Rice and wheat varieties were developed in such a way that they could tolerate large amounts of fertilizers. Owing to application of chemical fertilizers especially nitrogenous fertilizers, the crop become susceptible and prone to pest attack, so pesticide use increases. On the contrary, millet crops are hardy; do not require external inputs such as chemical fertilizer, and pesticides. It does not require a vast tract of irrigated land. But the aim of the chemical intensive agriculture was to externalize the agricultural inputs, they resulted in making us deeply dependent on these inputs.

Massive propaganda promoting chemical farming with monoculture pushed back the task of research in and promotion of our own high yielding Traditional Rice Varieties. Dr. R H Richharia, the famous rice scientist, the former Director of Central Rice Research Institute, Cuttack, was sceptical of japonica varieties being imported in India without plant quarantine as it would bring rice disease and pests of Japan. He had selected some of traditional rice varieties having yield potential of 5-7 tonnes per hectare. But such a situation was created that in 1967, Dr Richharia had to leave Cuttack, where he had been director of CRRI.

Mainstream media campaign aggressively pushed chemical intensive farming on ordinary farmers. Farmers slowly moved away from and forgot the benefits of folk rice like its low cost of cultivation, nutritive qualities, adaptability in marginal lands, economically and ecologically profitable fish-cum-paddy culture that is possible in traditional varieties of rice. Only the concept of low grain yield was pushed and acquired center-stage in all discussion and practices.

On the contrary, the yield of modern varieties declines after some years, until a new modern rice variety comes into the market requiring more and more chemical fertilizers. For example, in 1975, one kilo of nitrogen, phosphate and potassium fertilizer roughly gave 15 kilo grains; now it is the reverse: Farmers are using nearly15 kilo of chemical fertilizers to get 1 kilo of food grain.

The main intention of the Green Revolution was to introduce farming with chemicals and fertilizer responsive modern varieties. But the traditional varieties do not require chemical fertilizers and pesticides the same way, and the seeds can be used for years together.

What has been the impact of all this on crops, and on biodiversity?

India is one of the 17 mega diverse countries rich in flora and fauna including crop diversity. According to the National Bureau of Plant Genetic Resources in New Delhi, India had 82,000 rice, 38000 wheat, 10000 pigeon pea, 16000 gram, 3668 brinjal, 46000 various millets.

Since the introduction of the Green Revolution, there has been a colossal loss of our crop biodiversity that is the key to our future food security. Surprisingly, this fact doesn't find any mention in any of our textbooks. Now, we may not find even 2,000 traditional rice varieties in farmers’ fields of India. Researchers found that more than 98 percent of those varieties have been extinct from the farmers’ fields.

Representational image. Photo: Anupam Paul.

Some of the extinct rice varieties of Bengal, for example, are Pabashi, Kachanani, Hatirdani, Choto Josowa, Guligati, etc. The variety Guligati, deep-water summer rice – which can withstand stagnant water of 1 feet and above, over 25-30 days and is harvested in April -- of South 24 Parganas was last documented in 1998. So, it has been lost for future generations. We don’t have any such modern variety for deep water during Boro, or the summer rice period. Practically, no scientist can bring them back even if we can send the Moon Missions into space.

Why do you believe there is a need to conserve such traditional varieties of rice?

It is quite natural some crop varieties may be extinct with the passage of time due to non-cultivation or any weather aberration. Our forefathers meticulously selected and nurtured some of these varieties for future generations. Yet, modern policy makers are not documenting the traditional varieties’ features of nutrition, yield per litre of water, richness of iron, zinc and antioxidants, grain and straw yield, ability to adapt in marginal lands and lastly the grain yield.

Traditional rice varieties are the basis of future food security. We now need crop diversity more than ever as it also provides food security against natural calamities, as we witnessed during cyclonic storm Aila in 2009 in Sundarbans areas in saline zones.

Nutritious qualities of folk rice are still being fully analysed. But those that have been analysed so far have qualities that ought to make us take notice and pay attention to them. Many of these varieties are rich in anti-oxidants, beta carotene – precursor of Vitamin A, and cancer preventive anthocyanin particularly in red and black rice varieties. Unpolished rice is good for diabetes, for lactating mothers. are full of essential micronutrient minerals, such as iron and zinc.

What role can traditional varieties of rice play as society grapples with climate change? How are they more suitable to climate change and local agro-ecology?

All traditional varieties of rice are suitable for marginal lands like drought, flood, saline-prone areas. Some pre-Kharif rice(called Aus) rice varieties sown in the month of May- June can withstand high temperature and moisture stress in the soil. Some varieties can withstand drought at initial phase and flood at later stage. Daseriya rice of Bihar has this unique feature. Everywhere, we are experiencing climatic aberrations; rainfall is not evenly distributed, erratic and scanty, not suitable for Kharif rice (planted June to November). Traditional varieties of Aus rice can cope with this situation.

At the time of Aila cyclones in 2009 in Sundarbans areas in saline zones, most of cases all the so-called modern salt-tolerant rice varieties failed while the traditional salt tolerant varieties withstood the climatic vagaries. These are low yielding, but tolerate substantial salt whereas modern salt-tolerant varieties can give high yield in comparatively less salt affected areas.

But with the passage of time in the last few decades, suitable traditional rice varieties for marginal lands like deep water paddy, salt tolerant paddy, both drought and flood tolerant paddy, drought tolerant paddy, paddy for broadcasting in upland have declined significantly. West Bengal had more than 5,000 folk rice; apart from conservation plots, but we may find hardly 150 varieties in farmers’ fields now. Sadly, despite research, no modern rice variety can replace them or a match for them. No crops (be it hybrids, or Genetically Modified crops) in the world will be able to withstand extreme climate aberration that we are approaching.

Modern varieties, the High Yielding Varieties(HYVs), are designed so selfishly that its grain is meant only for humans. But in India, paddy straw is the main fodder for cattle and bullocks. But HYV of rice provides meagre fodder, and cattle do not eat it. The straw is not suitable for thatching, packing and mushroom production. The traditional varieties on the other hand provide adequate straw as fodder, mushrooms grow easily on the paddy straw in the monsoon months.

Anumeha Yadav is an independent journalist focusing on labour and rural policy.

This article went live on March second, two thousand twenty four, at fifty-nine minutes past six in the evening.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.