Is India’s $100 Billion Agricultural Export Dream Achievable?

Agriculture remains the backbone of India’s economy, employing nearly half of its population and sustaining rural livelihoods across the country. While the sector has ensured food security for over a billion citizens, its role extends far beyond that.

In 2024-25, India’s agricultural exports reached $51.9 billion. Despite being the world’s second-largest agricultural producer, India’s share of global agricultural exports remains modest at 2.2% (WTO Trade Statistics 2024). This stark contrast between potential and export performance underscores the untapped possibility in Indian agriculture.

The government’s vision of achieving $100 billion in agri-exports is an ambitious target. It represents the challenge of not only producing reliable surpluses, but also meeting high global standards of quality, as per Codex norms. This can also provide an opportunity to unlock economic growth for millions of farmers, integrate Indian agriculture with global value chains and position India as a long-term and dependable supplier of food products in international markets.

Realising India’s $100 billion agri-export dream

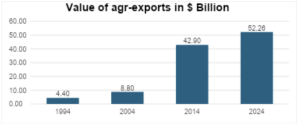

India’s agricultural exports have climbed from $ 4.40 billion in 1994 to $ 52.26 billion in 2024 (Chart 1). It doubled from 1994 to 2004 and increased almost 5 times from 2004 to 2014. Having crossed the $50 billion threshold in recent years, the sector now faces the challenge of replicating that growth trajectory. Strategic interventions and a diversified export portfolio will be essential to double export earnings from current levels.

Chart 1: Agriculture Exports (USD Billion) from 1991 to 2014

Source: World Stats, WTO

Historically, Indian agri-exports have remained skewed towards a few commodities with limited value addition, a trend shaped since the Green Revolution-era when procurement policies focused on cereals while horticulture and livestock production remained underdeveloped. It was only in 2005 that the National Horticulture Mission provided fillip to the horticulture sector.

Indian exports remain dominated by rice (both basmati and non-basmati), marine products, spices, sugar and buffalo meat, which accounted for 82% of the country’s agricultural export basket in 2024-25.

To reach the $100 billion target, it is essential for India to diversify its export basket and develop additional product categories.

Over the next 10-20 years, the production of rice in the north-western region of India could reduce due to depletion of the underground water table and increasing awareness about agro-ecology.

So, policy makers should be looking beyond rice exports and identify items of high-value, processed and value-added exports. These products command premium prices in developed markets (e.g. US, EU, Canada, Japan) which account for only about 30% of our agricultural basket, compared with 70% in developing regions who import low-value primary products.

For moving up the value chain, India has to not only diversify its export basket but also unlock exponentially growing demand for processed food in western markets. This could transform India from being an exporter of low-value primary products to a supplier of processed high-value products.

Table 1 shows the top ten processed food exports in 2024-25. India’s Agriculture Export Policy 2018, which set an export target of $ 60 billion by 2022 and aimed to double exports in the subsequent years, identified high-value and value-added agri-products as priority areas for strategic expansion.

Accelerating this shift requires large investment in food-processing clusters, upgraded value chains, robust quality-control infrastructure, and strategic branding, particularly around GI-tagged items. Cooperative models, such as Mahagrapes in Maharashtra, demonstrate how cluster development can boost farmers’ incomes, harness economies of scale, and meet global standards of quality and traceability.

Table 1: Top 10 processed food exports in 2024-25

| S. No. | Item | Exports FY 2024 ($ Million) |

| 1 | Miscellaneous Preparations | 1326.24 |

| 2 | Groundnuts | 860.73 |

| 3 | Cereal Preparations | 841.79 |

| 4 | Processed Vegetables | 787.28 |

| 5 | Pulses | 686.93 |

| 6 | Processed Fruits, Juices & Nuts | 682.58 |

| 7 | Guargum | 541.65 |

| 8 | Prepared Animal Feeder | 447.4 |

| 9 | Jaggery & Confectionary | 430.88 |

| 10 | Alcoholic Beverages | 375.09 |

Source: Ministry of Commerce

Diversifying India’s agricultural export destinations is crucial for reducing dependence on a limited set of markets. Currently, major importers of Indian agricultural products have been the United States, Vietnam, Bangladesh, the United Arab Emirates and Iran. The United States alone imports about about $5.5 billion worth of agricultural and allied products, making it a top destination. The recent hikes in tariffs imposed by the US have caused enormous uncertainty and disrupted shipments.

So, expanding market access to newer destinations in Europe and Africa (latter accounting for only 14% of India’s export basket) can help mitigate risks from trade barriers imposed by importing countries.

Infrastructure constraints and unstable policy

Infrastructural constraints hamper India’s competitiveness in global markets. Strengthening cold chains infrastructure, building modern warehouses, and integrating farmers with processors through robust value chains are critical to maintaining quality from farm gate to international markets. The Union government has been investing about Rs 11 trillion in infrastructure but most of the investment has gone to railways, roads, ports, airports, telecom, green energy etc. Sadly, there is no Agricultural Produce Market Committee in India which can match the infrastructure of the wholesale market in the EU or the US.

Unstable policy further undermines India’s agri-export ambitions. Frequent bans, export restrictions, and sudden imposition of Minimum Export Price on staples such as onions and non-basmati rice have damaged India’s credibility as a reliable supplier. For example, the ban on export of wheat products was quite surprising. Establishing stable, predictable and long-term policy frameworks is crucial to instil confidence among importers.

Compliance with the quality standards of importing nations remains another major challenge. For example, several non-basmati rice consignments have faced rejection in the EU due to high pesticide residues. While India imports large quantities of apples, almonds, cashews and other fruits, our own produce faces barriers due to gaps in meeting global standards. A lot more needs to be done to educate farmers to meet the recommended package of practices while applying pesticides.

India’s remarkable achievements in agricultural production can translate into export-led growth if we see an increase in productivity and if quality standards are enforced domestically. Achieving $100 billion of agricultural exports is not easy. We must plan for lower exports of non-basmati rice and work on other items of export.

Siraj Hussain is former Union agriculture secretary. Priyanka Bains is a Research Associate with Infravision Foundation.

This article went live on July thirty-first, two thousand twenty five, at thirty-nine minutes past three in the afternoon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.