Special | The Deadly Toll of Sugar on Marathwada's Soil

Maharashtra is the second largest producer of sugar in India. The water-thirsty crop is on the rise even in dry regions such as Marathwada at the cost of its soil and people's health.

A six-month investigation by The Wire explored the wide-ranging consequences of defying nature to grow water-intensive sugarcane in the region and why expansion continues.

In part one, we examine the ecological impact of sustaining the sugar boom in a dry region. Read part two here and part three, here.

§

Maharashtra’s sugarcane fixation has been brutal to its soil. Data analysed by The Wire shows that sugarcane occupies less than a tenth of the state’s agricultural land but sucks up four times more water than wheat. Two out of ten irrigated hectares grow sugarcane in the state. Experts say it leaves the soil dead in its wake. The crop’s insatiable thirst is supplemented with pesticides, fertilisers and water that is running out. Yet, farmers are at its mercy.

A deep dive into the 10-year area, production, and groundwater data in the state after scraping and analysing it as well as our own independent testing of a soil sample shows just how intensive farming of this thirsty crop is draining wells and slowly killing the soil. Despite this damage, its production has nearly doubled since 2012 in drought-prone Marathwada’s districts such as Beed, Jalna, Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar, and Parbhani when compared to the state average, according to our data analysis.

The investigation reveals that excessive sugarcane farming in Marathwada is depleting carbon from the soil, which plants need to stay healthy. Soil in most districts in Marathwada are also deficient in iron.

The Wire travelled to Beed, Dharashiv and Jalna, some of the districts with degrading soil in Maharashtra, to investigate why farmers grow sugarcane despite the consequences.

Drought-prone Marathwada ramps up sugarcane

Marathwada is a dry region of a rainy state: an unlikely candidate to go big on water-thirsty cash crops. The region receives approximately 800 mm of rain, lower than other regions in the state. Despite this, sugarcane thrives in Marathwada.

Some parts of Marathwada receive even less than the region’s already below average rainfall. Farmers in Sonimoha village of Dharur tehsil in Beed district, for instance, often complain of lack of water. That has not deterred Ramraj Tonde, a farmer, from growing sugarcane on half of his four-acre land.

Tonde remembers how he kept the crop “alive” in 2023 with borewell water. “We did a little bit of drip and sprinkler. That's why it's alive. It rained in June (2024). Some died and some survived,” says Tonde. Farmers like Tonde are used to the fluctuating weather pattern, but continue to depend on sugarcane.

Farmer Ramraj Tonde relied on borewell water to irrigate his crop last year. Photo: Amitha Balachandra.

Defying nature by drilling deeper is becoming the norm to keep up sugar production. As sugarcane farming grows, the use of groundwater in the region is also on the rise. Our analysis shows Maharashtra pumps nearly three times more water for irrigation than India’s average. The state’s production of water-thirsty crops such as sugarcane, rice, cotton and wheat, has increased by one and a half times over ten years compared to India’s average. A significant portion of the water is used to grow sugarcane. Farmers in the region, where droughts are frequent, end up using groundwater when the rain is inconsistent.

This water-guzzler needs anywhere between 1500 and 3000 mm of rainfall to grow well, exceeding the average rainfall of Marathwada. Beed and Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar districts used up more groundwater than other districts in the region between 2012 and 2023 to grow water-thirsty crops, according to Central Groundwater Board data.

The data shows that as of 2023, seven out of nine blocks assessed by the central groundwater board in the district of Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar were semi-critical when it came to groundwater extraction. Two out of eight blocks assessed in Dharashiv were semi-critical. One in 10 of the blocks assessed in Latur were semi-critical. This means the amount of groundwater being extracted is coming close to being exhausted. The other districts, including Beed, in the region were in the safe zone, meaning their groundwater extraction had not exceeded 70%.

Experts worry rampant sugar production would be a deterrent even for safe zones, particularly in drought years.”The Maharashtra Groundwater Act-2009 is in force, and it has many provisions that no one can drill deep-wells below 60 metres (approx. 200 feet). But there are no serious efforts at any levels implementing that Act on ground or regulating it, supervising its implementation,” says Eshwer Kale, senior researcher at Watershed Organisation Trust.

Government effort to slow sugar production fails

In 2016, when the region was reeling from a severe drought, with barely any water in the dams, the government called for a temporary ban on sanctioning new sugar mills in the region for five years. The verbal statement did not suppress sugar production. Our analysis of the government’s data shows a nearly sixfold increase on an average from 2016 to 2022. There has been a dip in production the last two years.

The Marathwada region is not the highest sugarcane producing region in the state, but the water stress here is an issue during drought years. Districts such as Ahilyanagar (formerly Ahmednagar) and Solapur in Maharashtra produce more sugarcane in the state overall. They also have high water stress, but also get better rainfall than Marathwada. Agriculture experts concede that the rate at which sugar is growing in Marathwada, which struggles for water in most years, is a concern.

“Earlier, wells were not more than 50 feet deep. Now, bore wells, tube wells, are more than 1000 feet deep. And that means all the soil water is depleted and the soil aquifers have become bankrupt,” says H. M. Desarda, economist and former member of Maharashtra State Planning Commission.

'Growing Jowar, Bajra not sustainable'

Sugarcane growth in the region means farmers are abandoning traditional, more labour-intensive crops such as jowar, bajra and ragi. The production of jowar went up in Beed, Jalna, Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar and Latur districts in 2016 due to successive droughts that made sugar difficult to grow, but has begun to dip again in the last five years.

Farmer Ramraj Tonde largely grows jowar, bajra and other pulses for personal consumption. It requires a lot of labour and the returns are low. Sugarcane, on the other hand, takes 12-18 months to mature and can be harvested multiple times with minimal labour.

Tonde is not the only farmer who has stuck to sugarcane. Mahesh Magar, a farmer in Dharashiv’s Shingoli village, switched to this water-thirsty crop in his five-acre land three years ago. He has drilled up to 500 feet to ensure there is enough water for the crop and is quick to dismiss jowar and bajra as unsustainable.

“The government gives ration to a number of people... Who is going to eat jowar? What's in the ration? Wheat, rice. They get it for 1 rupee a kilo. Who eats Jowar for 20 rupees a kilo?,” asserts Magar.

Left, Mahesh Magar at his farm in November 2024; right, Magar interacting with a labourer as the family prepares to sow sugarcane in his brother’s farm. Photos: Amitha Balachandra.

The Union government declared 2023 as the International Year of Millets. Maharashtra followed suit and launched ‘Millet Mission’ to encourage farmers to change their cropping patterns. When asked what the Maharashtra government has done in the last one year, R. S. Naikwadi, the director of agriculture, extension and training, said the government was “making an effort” and that they are “seeing a difference on ground” but there is “no data on demand”. Naikwadi admits the challenge is that these crops are labour intensive.

Farmers turn to less thirsty but still risky soybean

While millets have seen a slump, changing weather in the region has increased the production of short-duration cash crop, soybean, which brings profits and its own environmental risks. This rainfed crop does not require as much water as sugarcane. According to agricultural data from the Directorate of Economics and Statistics on area, production and yield, soybean has the highest area of cultivation in this region after cotton.

Farmers stick to cash crops such as soybean and sugarcane because of the returns. This, despite sugarcane’s yield in Marathwada being slightly lower than other sugarcane producing districts such as Ahliyanagar (formerly Ahmednagar) and Solapur. While soybean may be better for the water table, it has not improved the region’s soil quality.

“Farmers have gone after soybean or short duration cotton crops because that takes care of the changing weather and crop patterns. But that doesn't remain all the while because weather is not stable and this cropping pattern which has destroyed the soil fertility is not sustaining the yield,” says economist Desarda. “So, it is just like antibiotics, you take more pills and still it doesn't cure because of the resistance. Same way, the soils have become in a way dead.”

Flooding sugarcane fields adds to the water stress

Farmers flood their fields for sugarcane. This is particularly a problem in a dry region growing a water-thirsty crop as it leeches vital nutrients from the soil. Drip and sprinkler can help save at least half the water required for flood irrigation. Despite being one of the top five states leading in drip and sprinkler irrigation methods, the adoption is still low. Every four out of 10 hectares in the state is irrigated using drip, according to our analysis of the government’s micro-irrigation data.

The Union government and the state bear almost half the cost of both drip and sprinkler sets as subsidies to farmers owning five hectares of land under the ‘Per Drop More Crop’ scheme. Small and marginal farmers are given 55% subsidy whereas other farmers are given 45% subsidy. Maharashtra went a step further and said it would bear an additional 25% for small and marginal farmers and 30% for other farmers to push them to utilise the scheme.

Farmers, however, say there is a lot of delay in the government reimbursing their money. “When the budget comes, we have to give from our pocket. And after two to three years, the money is deposited in the account,” says farmer Mahesh Magar.

Apart from saving water, fertigation through drip – a method of applying fertiliser through an irrigation system – is also effective. Mahesh Waghmare, assistant professor of soil science and agricultural chemistry at College of Agriculture in Dharashiv says farmers flood their fields because it is an easy way out. “10 to 20 percent farmers are applying the fertiliser through fertigation. But they have the labour problem. And fertigation technology adoption is more cost(ly).” says Waghmare.

The bitter cost of sugarcane farming

Intensive sugarcane farming and flooding fields drain the region’s soil but farmers see no alternative. Ramraj Tonde, a farmer in Beed, admits his crop’s growth has decreased over time. He has to regularly add fertiliser to sustain his yield.

Left, farmer Ramraj Tonde examining his farm’s soil; right, Tonde’s store room featuring fertiliser and farm tools. Photos: Amitha Balachandra.

The region’s soil health data by the government mirrors the findings on ground. Most districts that are growing water-thirsty crops, particularly sugarcane, have poor soil health wherein these soils have lost many vital nutrients. The Wire looked at soil organic carbon data, which determines the quality of the soil.

Organic carbon regulates the crop’s ability to hold water. It also helps microbes thrive and is a vital indicator for soil health. Our analysis of soil data shows that most districts in this region have suboptimal organic carbon. Dharashiv and Parbhani in Marathwada have very poor organic carbon, according to the soil health card.

If the organic carbon is not optimal, which is the case in most districts, it leads to the imbalance of other vital macronutrients (nitrogen, potassium and phosphorus) and micro-nutrients such as iron, zinc, and sulphur.

The Wire analysed these vital nutrients in Maharashtra from the government’s soil health card and found that the soil in most districts of Marathwada are deficient in iron. Jalna, Beed and Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar districts have the worst levels of iron deficiency in the region. Low iron in soil causes yellowing of leaves and affects the growth and productivity of the crop.

Several other farmers in the region agree that the quality of the soil has suffered because of sugarcane, but feel they have no choice. Farmer Chhagan Andhale, who is also a party worker for BJP and a contractor for a sugarcane factory near Beed’s Pimpla village, primarily grows sugarcane in his 15-acre farmland and relies heavily on fertilisers as a quick fix to increase yield. “This year we have added 5 quintals [of fertiliser] for sugarcane. Next year we will have to add 1 [more] quintal for sugarcane. The fertility of the soil is decreasing. That is why every year we are adding more fertiliser,” says Andhale. All the farmers we spoke to grew climate-resilient crops only for consumption.

Heavy and indiscriminate use of fertiliser is a huge impediment to regenerating healthy soil. The Deputy Director of Agricultural Engineering department at the Maharashtra Institute of Technology, Deepak Bornare, regularly tests farmers’ soil samples in his government recognised private laboratory and often finds soil organic carbon very low because of farmers growing the same crop year after year and their reliance on fertiliser.

“If 1% (organic carbon) is there, then proper flora and fauna will be maintained, microbial count will be good, and further processing, where there is good conversion of fertiliser in different elements. To do that, living things are needed. If they are in proper quantity, then soil health will be maintained,” says Bornare.

Independent investigation: Findings from the soil sample

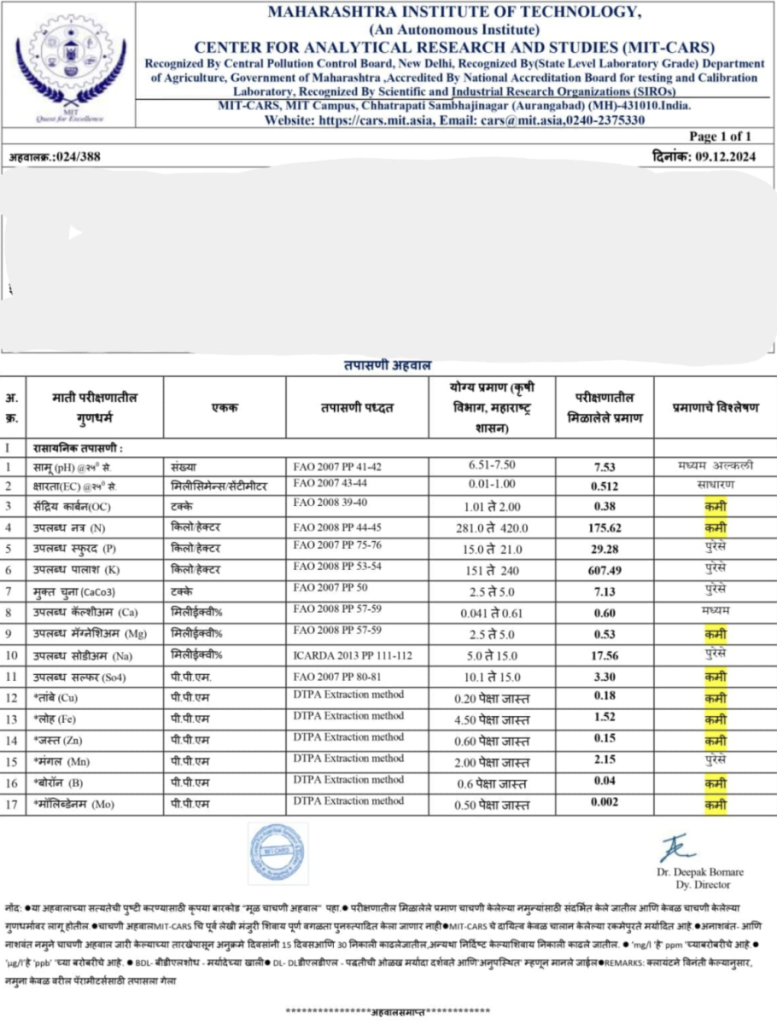

The Wire set out to do its own soil testing and came up with the same poor results that validate the official government soil health card. We collected a soil sample from Shivraj Nivare’s farm in Georai tehsil of Beed district with the help of the Krishi Vighyan Kendra (Agricultural Science Centre) officials, and gave it for testing at Maharashtra Institute of Technology’s private lab in Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar.

A worker helps this reporter collect soil from Shivraj Nivare’s farm. Photo: Amitha Balachandra.

Nivare last tested his soil 10 years ago. Like Nivare, several farmers in the region either don’t test their soil regularly because they don’t want to incur the expense or are not aware of the benefits of soil testing. Each district in the state has a Krishi Vighyan Kendra (Agricultural Science Centre) which serves as a knowledge and resource centre to help farmers with the schemes of the government along with other technology. These centres also help farmers test their soil for macro and micronutrients to determine how healthy their soil is.

Experts say that it is imperative for these officials to spread awareness on the benefits of soil testing. “It is important to go from land to lab but also from lab to land. Why is it not compulsory like the census? Just like humans and livestock, do a soil census also. Do a follow up every three years so that you have a benchmark,” asserts economist Desarda.

Nivare, who owns five acres of land in Georai’s Khamgaon village, had just planted sugarcane at the time of the collection in December 2024 after growing soybean in the kharif season.

The results of the investigation confirmed the soil health data findings and painted an even more grim picture. We found that the soil sample had low levels of almost all vital nutrients – including nitrogen, iron, and organic carbon. This was similar to the region’s data which showed how districts with heavy dependence on water-thirsty crops had low iron and organic carbon. The iron level in the soil was three times lower than the acceptable value.

The findings of soil that was independently tested showed poor quality in the region

But what happens to the food we eat when the iron levels in the soil are low? In part two of the series, we look at the health consequences of bad soil as a result of intensive monocropping and who pays the price.

Reporting for this story was supported by the Environmental Data Journalism Academy – a programme of Internews’ Earth Journalism Network and Thibi.

Data analysis for this series and the full methodology can be accessed here.

Note: An earlier version of this piece had quoted Mahesh Magar as having said that only about 20% of farmers he knows use drip. This has been removed.

This article went live on April fifteenth, two thousand twenty five, at zero minutes past six in the evening.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.