After 20 Years, Kotak Mahindra Bank Still Can’t Manage Without Uday Kotak

Banks are considered special, but Kotak Mahindra Bank (KMB) and its high profile founder-CEO, Uday Kotak are extraordinarily special. Ever since KMB was granted a banking license in 2003, Uday Kotak has been its CEO. As per the Reserve Bank of India’s directive, he will have to step down at the end of 2023.

But Kotak has always found a way around RBI directives; and so he has found one this time too.

To control the influence of founder-CEOs in private sector banks, the RBI deliberately framed a policy capping the CEO’s tenure at 12 years. With the RBI’s permission it could be increased to a maximum of 15 years. Pertinently, after 15 years, the banking regulator prohibited the CEO from being reappointed as the CEO for a minimum cooling period of three years and in that period the individual could not be associated with the bank or its group companies in any capacity directly or indirectly.

Although the RBI policy did not forbid a departing CEO from continuing as a director on the bank after completion of his or her tenure, the RBI has to date not given its nod to a former CEO continuing as a director in the same bank. This has not deterred the board of directors of KMB from approving (at its board meeting on March 18, 2023) Uday Kotak’s appointment as a non-independent, non-executive director from January 1, 2024. The voting by shareholders on this resolution will end on April 20, 2023.

Extract from Resolutions to be approved by KMB Shareholders on April 23, 2023

Source: Kotak Mahindra Bank

There are important implications of KMB’s decision to appoint Uday Kotak as a non-independent, non-executive director after he steps down as the CEO. It is a concerted move to defeat the spirit of the RBI directive, which aimed to control the influence of a founder-CEO after the individual’s tenure had ended.

Having Uday Kotak continue as a board member will effectively nullify the relevance of the new CEO, and even of the chairman of the board, as, in this analyst’s opinion, it makes the founder the backseat driver. Allowing a founder-CEO, who has been in charge for two decades, to continue now as a non-executive, non-independent director will make him the de facto CEO, albeit with none of the responsibilities.

This is why the RBI did not allow Rana Kapur to stay on as a director at Yes Bank after it had declined to renew his term as a CEO. Such a practice is also not healthy from a corporate governance perspective, as it creates a powerful rival centre of power on the board, undermining the authority of the CEO and the chairman.

The board’s decision to create a backdoor entry for Uday Kotak on the board of KMB is also indicative of its failure in succession planning. One of the key responsibilities of the board is succession planning at all levels in the organisation, and in particular for key posts such as the CEO, ensuring that the organisation is bigger than any individual.

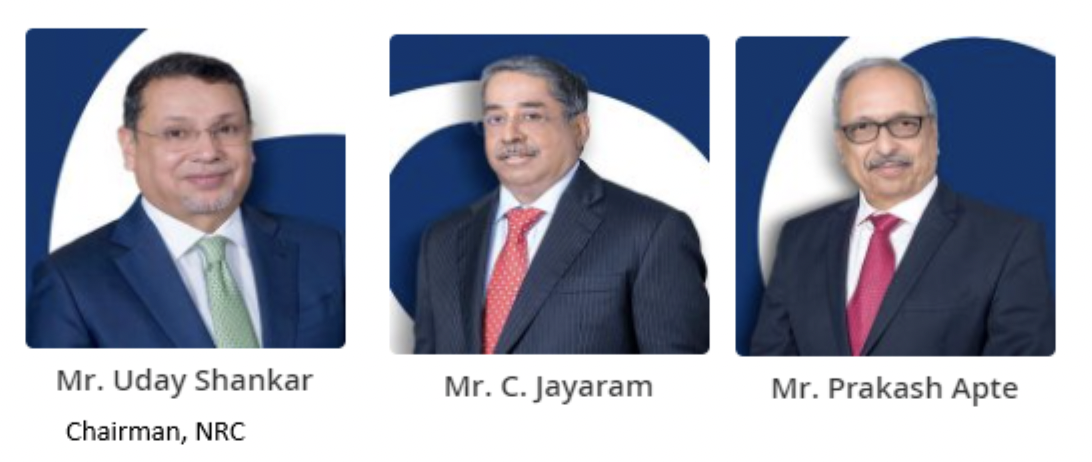

The brazen excuse of needing Uday Kotak’s continued expertise to assist the bank during the “present volatile economic scenario” and to take the “institution forward” reveals the abject failure of the board, and in particular the bank’s Nomination and Remuneration Committee (NRC), to groom successors over two decades of the bank’s existence.

In effect, the board of directors of KMB is publicly declaring that Uday Kotak is indispensable to the bank. This is the strategic fault line created by the bank’s board, for which stakeholders have to hold it accountable.

Kotak Mahindra Bank’s Nomination and Remuneration Committee

Source: KMB

The bank’s dependence on a single individual, even after two decades of existence, does not seem to be a concern for shareholders. Nor is it a concern for the credit rating agencies, which give the highest rating to KMB. These agencies are apparently oblivious to the huge ‘key man’ risk inherent in the bank. The Reserve Bank of India also has to be blamed for such a development, as it could have examined succession planning for the CEO in its annual inspections and highlighted the risk of the bank being overly dependent on a single individual. It is shocking that after two decades of Uday Kotak being the CEO, the board is publicly stating that the bank still requires his presence on the board to navigate the future.

The move to appoint Uday Kotak as a non-executive, non-independent director for 5 years commencing from January 1, 2024 should also be seen in the light of the announcement made on May 26, 2022 of appointing with much fanfare, the then 32-year old Jay Kotak, Uday Kotak’s son as a business head in the bank. The fast tracking of his relatively inexperienced son to an important post by the board of directors on “merit” is an indication of the future succession planning.

During Kotak’s 20 years as CEO, the banking regulator had given him significant concessions pertaining to dilution of founder ownership, which were not granted to other private sector banks.

When the RBI finally attempted to enforce its writ regarding lowering the founder shareholding in KMB, the bank defiantly responded by taking it to court, stating that the regulatory action was:

“…without jurisdiction, wholly illegal, ultra vires the BR [Banking Regulation] Act, manifestly unreasonable, arbitrary, unfair, without the authority of law, and unconstitutional…”

In response, the RBI accused KMB of “wilful misrepresentation”, “mala fide intent” and “taking the regulator for a ride” and also disrupting and undermining the regulatory systems of the regulator.

Strangely, and despite the harsh language exchanged, the RBI meekly settled the case out of court on terms favourable to Uday Kotak. The bank’s general disdain for regulation is not reserved only for the RBI: when the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI), the capital markets regulator, hauled up senior executives of Kotak Mahindra Mutual Fund (a subsidiary of KMB) for major violations, the board, instead of punishing the executives, decided to reward them with promotions.

The market appears to be least concerned regarding such corporate governance practices – as long as the immediate performance of the company is not impacted. It is only when a major setback happens that such poor corporate governance practices are highlighted and condemned in retrospect.

Hemindra Hazari is a Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) registered independent research analyst

Disclosure: I (Hemindra Hazari) own equity shares in KMB, mentioned in this report. Views expressed in this piece accurately reflect my personal opinion about the referenced securities and issuers and/or other subject matter as appropriate. This article does not contain and is not based on any non-public, material information. To the best of my knowledge, the views expressed in this Insight comply with Indian law as well as applicable law in the country from which it is posted. I have not been commissioned to write this piece or hold any specific opinion on the securities referenced therein. This is for informational purposes only and is not intended to provide financial, investment or other professional advice. It should not be construed as an offer to sell, a solicitation of an offer to buy, or a recommendation for any security.

This article went live on April twenty-first, two thousand twenty three, at fifty minutes past four in the afternoon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.