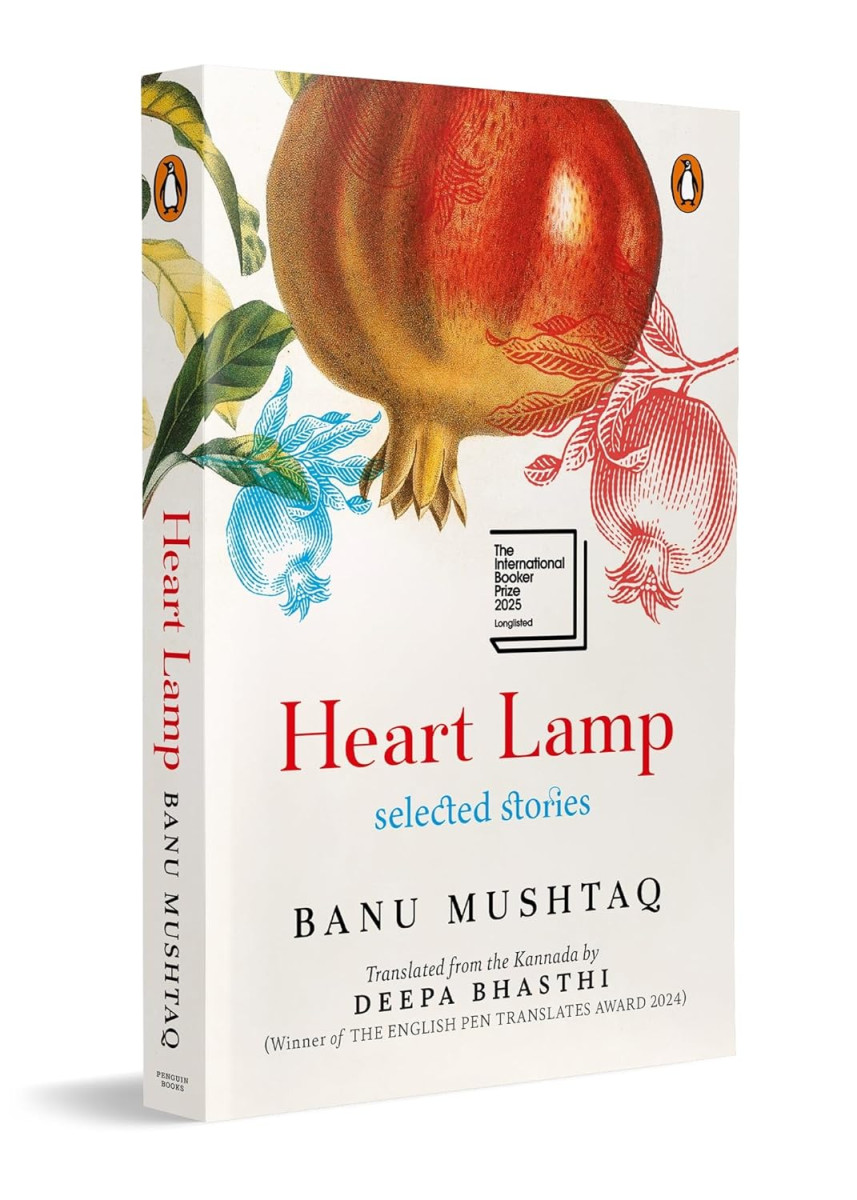

Humour, Scepticism and the Realities of the Familial in Banu Mushtaq's 'Heart Lamp'

The diversity of the seething everyday life of certain classes of southern Indian Muslims is showcased in swift, confident strokes in Kannada writer Banu Mushtaq’s Heart Lamp: Selected Stories (translated by Deepa Bhasthi). The edition unfortunately does not fully clarify when each story was written, but the blurb indicates these were written between 1990 and 2023, even as Mushtaq is linked to literary movements from the 1970s onward. The helpful translator’s note informs us that Mushtaq’s Kannada/Dakhni is brewed from a lively mix of Persian, Dehlavi, Marathi and Telugu.

Even though English must partially flatten, much of the humorous, wide-eyed energy of the stories does come through. Bhasthi argues that it is not enough to Anglicise Indian words – rather, that Anglicisation must carry the flavour and sound of the region that is being translated. Thus, rotti instead of roti, and lungi and panche instead of dhoti, and the Kannada-inflected khabaristan instead of the more ‘accurate’ Arabic-laden qabaristan.

Banu Mushtaq, translated by Deepa Bhasthi

Heart Lamp: Selected Stories

Penguin, 2025

Translations must thus negotiate familiarity and distance. One must not assume that a reader can eavesdrop at any home; and yet, the pleasure of eavesdropping is also to see all the clashes of similarity and difference. Many of the stories deal with the family, for example, and Mushtaq, who is also a lawyer active in social causes, both reaffirms and undermines the centrality of the family by introducing barbed questions of property, marital distress, the education of professional women, livelihood and parenting, and so on.

What makes this literary and engaging is that Mushtaq carves enough distance from these perennially stressful issues. There is much descriptive humour, a love of describing faces and attitudes reminiscent of leisured nineteenth century novels: “That their thoughts went in the same direction was proof of their friendship. He was an expert in deducing the mutawalli saheb’s moods from the ups and downs of his face, the latitude and longitude of the movements of his eyebrows, the quivering of his moustache, the lines of his nose and the lines at the side of his mouth. He would tailor his words, his behavior, the bend at his waist accordingly.”

The shrewdness of Mushtaq’s writing is that it is sometimes unclear if the tone is only that of humour, and not also that of scepticism and menace. For example, here is a description of a body being transported to be buried in a cemetery after it was inadvertently misplaced: “Finally Nisar’s body was exhumed. The mutawalli and his follower’s draped the rotten body in the brand new, starched shroud they had brought with them. Since the body was too rotten for ritual bathing, holy water was sprinkled on it. The foul smell made them want to retch, but no one showed it on their faces. The policemen covered their noses with their handkerchiefs…They had poured on copious amounts of scent and covered the top of the bier with a chador made of strings of jasmine to mask the smell of rotting flesh. None of the jasmine buds had bloomed.” The black humour continues, corpses continue to be mislaid: “Was it a Hindu corpse? Was it a Muslim corpse? The body was too rotten to be identified. Should it rot her, should it rot there.”

Banu Mushtaq. Photo: Facebook/Banu Mushtaq

Astringent humour continues to serve as social commentary. Here is an example from another story titled 'A Decision of the Heart': “The first option was to give talaq to Akhila. But given that he really loved her, and that they had four small children, he decided that was no answer. Apart from her intense irritation with Mehabood Bi, Akhila was a good woman. Also, if he gave her talaq, there was no way he could stay in town. Wouldn’t her brothers break his arms and legs?” Such passages put one in mind of the works of Anees Salim.

There are stories however that work on a more consistently grave register. This includes the last one, “Be a woman once, Oh Lord” (the deity is also addressed as Prabhu), where the tone retains a more job-like questioning, a whole life poured out in angry bewilderment at endless obfuscations of tradition and avuncular patriarchy: “I has asked three or four simple questions, to which I received thousands of answers in reply.” Shot through the despair are still some desperately hopeful imaginations of what marriage somewhere may still be: “If only I had been his backbone and he the hands that would wipe my tears away…”

As noted, it would have been helpful if the chronology and rationale of the ordering of stories were explicated. One would then have had a better sense of Mushtaq’s evolving sensibility, her responses to her own maturing imagination. Yet, even as it stands, much is gained: an introduction to many readers to a voice that can be playful, despondent, forgiving, and often just minutely and detachedly observant. The work is a testament to the riches of writing that one continually finds in India – whether the axes that one chooses to explore be that of region or gender or language or profession or religion.

Nikhil Govind is the author, most recently, of The Moral Imagination of the Mahabharata (Bloomsbury, 2023).

This article went live on May sixteenth, two thousand twenty five, at eighteen minutes past ten in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.