Kashmir’s 1.5 Million Shiites Can't Fit Into a Single Mould – Neither Can Their History

In downtown Srinagar, there’s a red-brick mosque with sloping green roofs overlooking the muddy waters of Jhelum. Its tall spire is made of small wooden slats, and crowned with a crescent-shaped brass finial that soars out skywards. This is where Islam treaded one of its first tentative footsteps in Kashmir in the early 14th century.

Sayyid Sharafu’d-Din, a reclusive Uyghur dervish from north-western (modern day Xinjiang) China had been camping out here for months. One day, Sharafu’d-Din was ushered in the presence of Rinchana, the enterprising Buddhist prince from Ladakh who, while on a military expedition to Kashmir, had overpowered the last of valley’s Hindu generals, heralding himself as the new ruler.

As the apocryphal story goes, an all-absorbing conversation with Sharafu’d-Din captivates the young royal, leading to his initiation into Islam. Rinchana takes up a new name; Sadru’d-Din, and becomes Kashmir’s first Muslim sovereign.

This story is quite well known in Kashmir where Bulbul Shah, as Sharafu’d-Din is popularly known, features among the pantheon of Sufi mystics whose teachings undergird the religious sentiments of the region’s predominantly Sunni Muslim population. But what is probably less acknowledged is that Sharafu’d-Din’s beliefs also reflected a marked predilection towards the doctrines central to Shiʿa Islam.

Bulbul Shah or Sharafu’d-Din's shrine. Photo: Twitter/@jameelyusuf

The source of this information is a 400 year old Persian text Baharistan-i-Shahi that was first to narrate in detail the encounter between Rinchana and Sharafu’d-Din, and is permeated with references eulogising Ali Ibn Abi Talib, the first Shiʿite ‘imam.’

Nearly 130 years later, Khwaja Azam Dedhmari, a Sunni historiographer, too mentions the same incident in his famous Tarikh-i-Kashmir, but omits all allusions to Ali, allowing the redacted version of this story to prevail that ends up characterising the foundational moment of Islam in Kashmir in purely Sunni terms.

'Shi'ism in Kashmir: A History of Sunni-Shia Rivalry and Reconciliation,' Hakim Sameer Hamdani, I.B. Tauris, 2022.

So why is this aspect relatively unknown?

The answer probably is that there has been very little scholarly attention that interrogates the historical perspective of Kashmir’s 1.5 million Shiʿite inhabitants. It is this gap that Hakim Sameer Hamdani’s ambitious new book Shiʿism in Kashmir: A History of Sunni-Shiʿi Rivalry and Reconciliation seeks to fill.

Hamdani, who works as a Design Director at Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH) J&K, draws on rare manuscripts – some of which have been lying untouched in the safekeeping of few prominent Shiʿite families in Srinagar. The result is a highly resourceful book that navigates masterfully through the Shiʿite aspects of Kashmir’s history.

The snippets regarding the Islamic history of Kashmir narrated in the book are quite revelatory; not many would know that the earliest references to Muslim presence in Kashmir are featured in Shiʿite hadiths (sayings of Prophet Muhammad) compiled by Shaykh Yaqub Kulyani. The hadiths describe a meeting between twelfth Shiʿa ‘Imam’ al-Mahdi and Abu Said Hindi, a Kashmiri adventurer who visits Baghdad city in the 9th century.

There is a small summary about the historic (and mostly legendary) hostility between Shaykh Hamza Makhdum (representing the Sunni side) and Shams-al-Din Iraki (The Nurbakshi Sufi mystic who introduced Shiʿism in Kashmir).

The Mughals conquest of Kashmir though – which locals still recall as a traumatic event – is elaborately explained, for its reasons are rooted in the sectarian skirmishes.

It starts with the execution of a Shiʿa soldier Yusuf Inder who is charged with injuring a Sunni khatib (preacher) of Jamia Masjid during a brawl.

The matters reach the royal court where senior jurists question the judgment and order execution of three qadis (judges) who signed Inder’s death sentence. One of the judges Musa Qazi – although this episode happens much later – is ordered to recite the name of Ali, the first Shiʿa Imam in Friday khutba (sermon).

He refuses to oblige and is executed for it, stirring the Kashmir’s Sunni nobility into protest. Some of them implore Akbar for help who uses it as a pretext to launch a full scale invasion of Kashmir.

While not much is mentioned about the state of Kashmiri Shiʿas under the Mughal period, it is the Afghan rule that goes on to become the crucible in which Shiʿa identity, as a community distinct from – and sometimes on oppositional terms with – Sunnis starts to solidify.

Afghans unleash a wave of persecution against Kashmiri Shiʿites. In 1788, the Zadibal Imambada is gutted under the orders of the Pashtun administrator Juma Khan Alkozi. In 1801, another Afghan governor Abdullah Khan comandeers mobs that destroy the historical Imambada once again, engaging in pillage and sexual violence against Shiʿas.

Faced with the relentless restrictions on their ritual ceremonies, Shiʿas in Srinagar start constructing tah-khana (basements) in their houses “where they could discreetly recite marṣiyas during the month of Muharram.” The despondency of Kashmiri Shiʿa is articulated in the tradition of writing and compiling marṣiyas. (elegiac poems)

The political estrangement leads Kashmiri Shiʿas to seek patronage from the Iranian merchants visiting Kashmir in large numbers. Kashmiri calligraphers like Muhammad Husayn are known to have drawn beautiful Quran codices for their Iranian patrons.

The reconstruction of Zadibal Mʿārak in 1830 was overseen by an Iranian merchant, Ḥajji Baqir, who had married into the family of the Mʿārakdars, the hereditary (custodians) of the shrine.

The Zadibal Imambara. Photo: Facebook.com/iZadibal

Another response to the campaign of endless persecution is characterised by the outward migration of Shiʿas to the state of Awadh – a historical region in north India corresponding to the modern day Uttar Pradesh – where they built their lives from scratch. Some influential Shiʿas even took part in administrative affairs of Awadh.

Sayyid Safdar helped establish Usuli school of Shi’a Islam as the region's official jurisprudence. Others like Mehdi Khan set up judiciary and police systems in Awadh.

In 1819, as Sikh rule replaced the Afghans in Kashmir, Shiʿas found the stranglehold of Sunni sectarianism coming loose. As a result, many in the community were lured by the idea of religious reassertion.

On the day of Ashura in 1830, an argument allegedly over the distribution of bulrush stems – used for weaving mats – morphed into a big confrontation as the Shiʿa mourners were accused of blaspheming Islam’s first three Caliphs (Prophet’s successors). This leads to yet another glut of anti-Shiʿa violence in Srinagar.

In early 1850s, the issue of disbursal of khums (remittances) from the Awadhi Shiʿas resulted in the dissension within the Kashmiri Shiʿa community. This division occurred between the Shiʿa aristocracy and the traditional custodians of Zadibal, the Mʿārakdars. The pattern of distribution which was controlled by the Rizvi Sayyids, and later by the Ansaris, alienated the Musavi branch of Kashmiri Shi’ites.

The split compartmentalized the Shiʿa community into Firqa-i-Qadim and Firqa-i-Jadid. These fissiparous tendencies were laid to rest briefly in 1872 when another spell of anti-Shiʿa violence broke out in Srinagar.

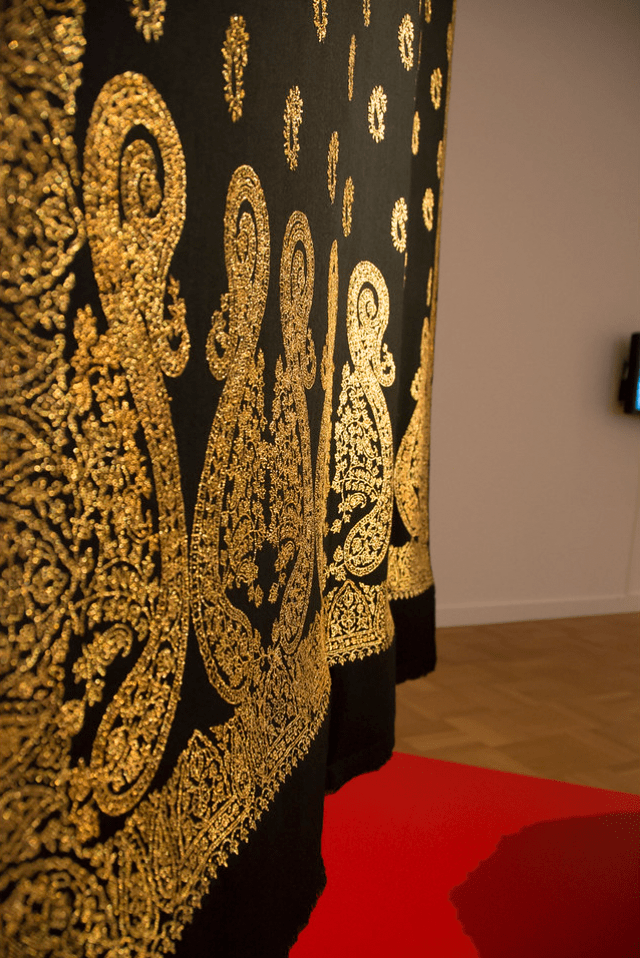

A Kashmiri shawl display. Photo: Pomax/Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

These riots took place in the backdrop of Franco-Prussian war which portended ruin for the industry of Kashmiri shawls as the demand plummeted on account of conflict in Europe which was their prime market. The economic crisis triggered a sense of discontent among Sunni shawl workers employed at the kar-khanas (factories) owned by mostly Shiʿa merchants.

But Hamdani adds that rival Sunni traders and religious leaders added fuel to the fire by stoking religious insecurities over the issue of construction of a mosque near the shrine of Madin Sahib in Zadibal, leading to build up of sectarian tensions that ended in bloodshed.

Hamdani describes how the distinctiveness of the community was reinforced further as the Dogras incorporated the Shiʿa artisanal class into their patronage system, employing them mostly as calligraphers and tutors of Persian language. We also get to read about the powerful chief physicians of the Dogra kings who are almost invariably Kashmiri Shiʿas.

But despite this, a sense of rapprochement also began to grow as Muslim opposition to the Dogra state started to accelerate.

One of the first expressions of this camaraderie was reflected in a tract published by the Mirwaiz led Anjuman-i-Nusrat-al Islam to mark its annual conference which for the first time uses a respectful term Ahl-i-Tashi for the community, against the old pejorative word ‘Rafizi’.

Around the same time, reformist Shiʿa organizations like Anjuman Imamiyya and Hami-al-Islam also began to surface who were also, among other things, amenable to the inter-sectarian detente.

Another reformist group coalescing under the banner of Anjuman-i-Behbudi-Shiyan-i-Kashmir got Nauroz listed as a State Holiday. Same group would go on to introduce the idea of Friday congregational prayers – a common ritual tradition in Sunnis – among Shiʿas in Kashmir.

The group’s key organiser Munshi Ishaq founded a newspaper, Zulfikar, which championed the interests of the Shiʿa community (It was closed by the Dogra durbar in 1937). Ishaq became an associate of Sheikh Abdullah in the 1930s.

But the Anjuman faced backlash from the two leading Shi’a firqas and on the day of the proposed namaz-i-juma (Friday congregational prayer) in Zadibal, the two sides came to blows. The Anjuman was denounced for its “un-Islamic” tendencies, and the group receded into oblivion.

In 1907, a decisive move that marked the coming together of Shiʿas and Sunnis was a petition filed on behalf of Kashmiri Muslims to the Dogra state. “In addition to leading Sunni figures of the city, Mohyi-al Din, Sana-al Lah Shawl, Mukhtar Shah Ashai, and Sana-la lah Qadri, the signatories also included two Shiʿi: Aga Sayyid Ḥusayn Shah Jalali and Ḥajji Jʿafar Khan,” Hamdani writes.

Yet another expression of the concord was seen in the year 1923. It was the first time the Ashura procession was being taken out during the day time in Srinagar but the mourners had to contend with the prohibitions imposed by the Dogra state.

“The durbar’s order for an early morning procession was defied by Jalali who was supported by Saʿad-al Din Shawl, one of the leading Sunni (figureheads) of the city. An attempt by the mourners to proceed to the main road was thwarted by the police when Ram Singh the Superintendent of Police confiscated the tʿazia (Quran carried in a small casket)” Hamdani writes.

The political opposition spearheaded by Muslims against the Dogras would only go on to deepen. The most vociferous political action came from the Reading Room Party, among whose original founders were three brothers from a prominent Shiʿa family in Srinagar; Hakim Ali, Hakim Ghulam Safdar and Hakim Ghulam Murtaza.

Shiʿism in Kashmir is a brilliant corrective to the established narratives about the Kashmiri Shiʿas, most of which try to frame the community into a monolithic mold. Hamdani’s book paints the history of the community in a baroque detail and convinces us about the fact of how fluid it actually is.

This article went live on February fifth, two thousand twenty three, at thirty-seven minutes past four in the afternoon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.