It is easier said than done for a journalist to attempt a biography and avoid reducing the work into hagiography. All the more so when it happens to be of a political personality like V.P. Singh – hated for one decision or another, or an icon for those who respect him. With The Disruptor: How Vishwanath Pratap Singh Shook India, Debashish Mukerji has shown the way.

The book is an eminently readable biography and those who choose to read the 443 pages to know the subject – Singh’s persona and the socio-political context in which he evolved – will certainly profit immensely. Mukerji has thus filled a gnawing gap that was left by two earlier attempts – Janardan Thakur’s V.P. Singh, The Quest for Power (1989) and Seema Mustafa’s The Lonely Prophet: V.P.Singh, a Political Biography (1995).

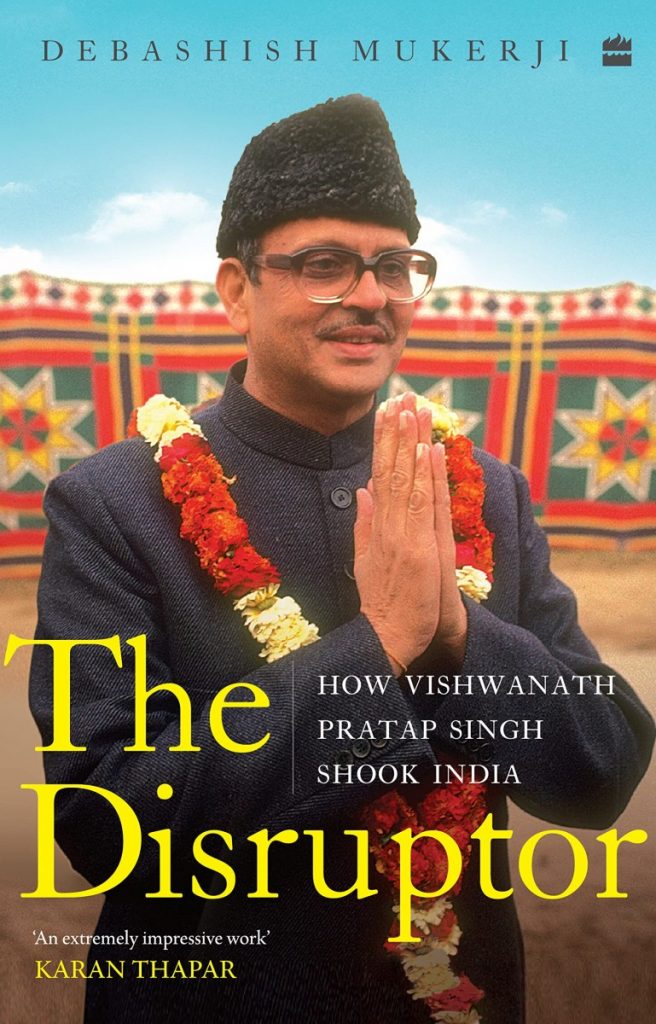

Debashish Mukerji

The Disruptor: How Vishwanath Pratap Singh Shook India

HarperCollins Publishers (November 2021)

Reading Mukerji’s account of Singh took me back to the experience that I had with Katherine Frank’s Indira: The Life of Indira Nehru Gandhi (2007). Mukerji treats his subject, tracing some of his traits, his time as India’s prime minister, the sense of insecurity that Singh had from his childhood in the same way that Frank treated Indira. Mukerji locates the seeds of Singh’s idealism from here and also the fact that from his early childhood to becoming an adult, Singh had a feeling of loneliness and remained a loner for most of his life.

Mukerji, incidentally, tells the story of Singh’s unflinching loyalty to Indira Gandhi and none else. The book says that Singh let go of his idealism, particularly in the realm of political morality, when it came to standing by and standing with Indira’s actions, including the Emergency. This was a misdeed, the author says. He tells us Singh’s actions were driven by Indira’s decision to prop up Singh rather than his brother Sant Bux Singh, who was already a Congress MP and aspired to rise up the ladder.

However, there is little in the book about Sanjay Gandhi and Singh and how they perceived each other. One is left wondering whether the folklore about Singh being a part of the Sanjay fanboy band is true or not.

It is believed that Singh was convinced that he should exit the world of elections and politics after quitting as Union defence minister on April 11, 1987. Mukerji, however, would like the reader to think this over and conclude otherwise. He cites Mark Tully’s journalistic account as well as Janardan Thakur’s telling that Sant Bux Singh had said that Singh would serve his cause – to become the prime minister – better if he resigned. The idea that Singh saw himself becoming the prime minister in April 1987 is a long shot. None had even an inkling, on that day, of what would unfold only a few days later – the story of kickbacks in the Bofors gun deal – on April 16, 1987, and the slew of events which sent Rajiv Gandhi and his Congress party scurrying for cover until the general elections in October-November 1989.

This is where Mukerji’s reliance on Sompal, the one who had remained Singh’s conscience keeper, so to say, to tell the story is useful. The book cites Sompal recalling how Singh felt attacked by all and sundry at the Congress party’s rally at the New Delhi Boat Club on May 16, 1987. Mukerji also reveals that Singh went to the Boat Club even after he had been marginalised by the Congress and called a traitor on the floor of parliament because he considered it his duty as a Congress MP.

The one aspect where Mukerji’s work clearly stands apart is that all these events and narratives are supported by interviews he conducted with those who were close to the subject and sustained by the transcripts of Singh’s long interviews archived at the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library. A journalist by profession, Mukerji displays the skills of a historian in his work. It is necessary to make this point here, given the hesitancy of most contemporary historians to write the history of our times and their comfort with restricting their concerns to the pre-independence era.

The book also tells the story of how the historic decision to implement the recommendations of the Mandal Commission through a host of interviews. The author does not hide his opinions on the subject. He admits that the book is driven by his empathy for a person who had a profound impact on Indian politics. Mukerji is not one of the many New Delhi journalists whose liberal façade falls apart when challenging the monopoly of some castes on the instruments of power. He is clear that the Mandal decision was as much a constitutional imperative and that its implementation in August 1990 was much delayed.

Also Read: 30 Years On, Mandal Commission Is Still a Mirror for India

But the book could have done with closer scrutiny of some players in the Janata Dal such as George Fernandes and Ramakrishna Hegde, both of whom, like Sompal, ended up working with the BJP-led NDA in 1999. Or such others as Madhu Dandavate and Surendra Mohan, who remained firm in their commitment to their political ethos and refused to let their moves be determined by the quest for ministerial offices. This, I say, because they were leaders who had dominated the anti-Congress space before Singh’s emergence as its leader in 1988.

V. Krishna Ananth teaches history at the Sikkim University, Gangtok. Among his books is Between Freedom and Unfreedom: The Press in Independent India.