Charles Sobhraj, the Average and Slippery Bloke With Notions of Being a Super-Criminal

Farrukh Dhondy, who was Charles Sobhraj’s arm’s-length friend for much of his corpse-strewn career, leaves what the reader really wants to know for the epilogue: “How did he manage to seduce so many women ― is he really charismatic and charming?” Dhondy reports that he is “an average bloke”, but “there was something in his gaze which was vaguely compelling”. Elsewhere, he comments on his “joyless” eyes, but declines to play Freud or Desmond Morris.

It’s a pity, because Dhondy is one of the very few people who can explain the weird animal magnetism which still draws millions to the Sobhraj canon. He has maintained relations with the serial killer since 1997, when Sobhraj approached him at Channel 4 to get a book published and a movie made on his life. Dhondy introduced him to Giles Gordon of Curtis Brown, who fled rapidly. In Hawk and Hyena, Sobhraj says that he wants to write like Jean Genet, but since his life is essentially a series of failed business plans, littered with corpses like found objects in an installation, his book may well have read like a blood-boltered spreadsheet.

Dhondy was more patient with Sobhraj than Gordon. Over the decades, he reveals, the killer approached him with outrageous demands, from asking him to be the genteel English front for an international drugs and arms business, to buying him a hot air balloon to escape from jail in Kathmandu. Dhondy was in it for the stories, and for a confession which never came.

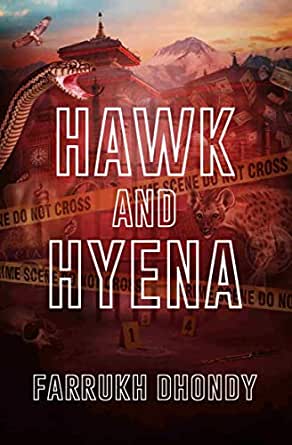

Farrukh Dhondy

Hawk and Hyena

Copper Coin/Bite-Sized Books, 2021

Dhondy joins the dots of Sobhraj’s extraordinary claims, scrawling connections across huge information voids, to create a thriller whose scope Robert Ludlum would have admired. The story begins in the picturesque village of Grantchester, outside Cambridge, where Dhondy took Sobhraj to meet a CIA man. The narrative travels via New England, London, Paris, San Marino, Bahrain and Iraq to Kandahar, India and Nepal. The cast of characters includes Boris Johnson playing editor of the Spectator, Arnab Goswami playing a journalist and Masood Azhar playing someone who’s just not himself. The Azhar thread runs right through the narrative.

Arrested in 1994, Azhar was in Delhi’s Tihar Jail and unpopular with the “thieves, rapists, murderers and other patriotic Indian convicts”, who showed “their love for their motherland by beating him to a pulp”. Sobhraj, who appears to have had literally bought over the jail, had the Pakistani terrorist rescued, medically treated and housed in the ‘luxury wing’ which he had created. They shared his meals, brought in from Delhi restaurants. Ironically, the same year, Kiran Bedi won the Magsaysay Award for her reforms in Tihar, an honour which she has used to advantage in her political career.

Years later, during the IC814 hijack drama in 1999, Sobhraj called Dhondy to offer to intercede on behalf of the Indian government. The purpose of the hijackers was to spring Masood Azhar from Tihar, and Azhar owed Sobhraj a favour. Dhondy did pass on his offer to the Indian authorities, but it was declined by the Vajpayee government, which met the hijackers’ demands and set Azhar loose, beginning a fresh cycle of violence in South Asia.

Also read: When Charles Sobhraj Walked Into My Office

Taking up Sobhraj’s offer could have been interesting in a perverse sort of way, because he had apparently double-crossed Azhar in Tihar Jail. He had lent the trusting terrorist his contraband cellphone to connect with his people in Kashmir, harvested the numbers of over 20 terrorists from the call logs and offered them to RAW in return for India rejecting changes to an extradition treaty which would have delivered him to a firing squad in Thailand, for several killings there.

Farrukh Dhondy. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

In fact, he had staged an escape from Tihar and recapture in Goa to gain an extra sentence which would keep him from being extradited. Dhondy tries to solve the last mystery of Sobhraj’s career: why did he return to Kathmandu, where he was wanted, and play blackjack for nights on end until he was recognised by a newspaper editor and arrested? He sees a complicated John le Carré-esque plot involving the Taliban, organised crime and a double-cross, at the end of which Sobhraj would be settled by the CIA in a safe house ― or a ranch in Wyoming so lonely it just had to be safe, except from himself. He admits that it is a journalist’s hunch rather than formal journalism, connecting dots in the absence of adequate information.

Nevertheless, Dhondy’s account is a page-turner because he is an embedded journalist kicking and screaming to be let out, yet unwilling to rush out the door for fear of missing a great story. Murderous empires embed drab journalists, like the Americans did in Iraq. To be embedded by a murderer in his own life story must be a much more interesting experience. The tension between Dhondy’s willingness to play along, his scepticism about a born liar and the creepy feeling that the liar is nevertheless telling the truth ensures that this riveting story is covered from multiple viewpoints.

But in journalism, facts are sacred: if Sobhraj’s account of the Tihar episode is true, we learn two facts, both depressing. One, terrorist mastermind Masood Azhar doesn’t have the brains to erase his call logs. And two, international criminal Charles Sobhraj’s top priority is the wholeness of his skin, not the selfish flamboyance of his life. The title of Dhondy’s book asks if he is a predatory hawk or a hyena in search of carrion. But he seems to be a survivalist cockroach.

Also read: Charles Sobhraj – Fixing the Heart of a Heartless Man

In Dhondy’s account, Sobhraj revels rather childishly in his reputation as a super-criminal but cleverly, he never actually admits to the murders he committed or planned, often for petty cash or just a passport, which he could doctor to take on a dead man’s identity. At one point, he sells the property of his partner Chantal and blows it up in casinos in France and the UK. The house wins, as advertised. Cleaned out, he can’t even pay his parking bill and get his car out of a lot on Edgware Road, and must touch Dhondy for a loan. From which we learn another interesting fact: Sobhraj exists outside the formal financial system. He doesn’t even have a credit card.

Through his career, especially his stint in Tihar Jail, Sobhraj sought out the phone numbers of many journalists in South Asia and elsewhere, and stayed in touch with them. Each of them thought of themselves as special, chosen for intimacy by the killer ― though Dhondy was clearly specially chosen. In retrospect, one wonders what the journalists got out of it. Sobhraj’s life is small. He started as a car thief in Mumbai and his prospects remain nugatory. He killed for peanuts and depended on petty bribery to stay alive. He is no Arsène Lupin. He’s just Gurumukh Bhavnani, renamed Charles Sobhraj by his stepfather in wartime Saigon. That cruel little act of depersonalisation, Chantal suggests in Dhondy’s account, may have set the ‘bikini killer’ on his career of callous misanthropy and murder.

Journalist and literary translator Pratik Kanjilal is editor of The India Cable.

This article went live on May thirty-first, two thousand twenty two, at zero minutes past two in the afternoon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.