The sport of squash, it is said, was devised in a London prison, where occupants entertained themselves by hitting a rubber ball against the courtyard walls. These walls were eventually fashioned into the modern squash court – a glass room to contain a player, an opponent, a ball and their rackets.

The sense of loss was devised out of life and its absence.

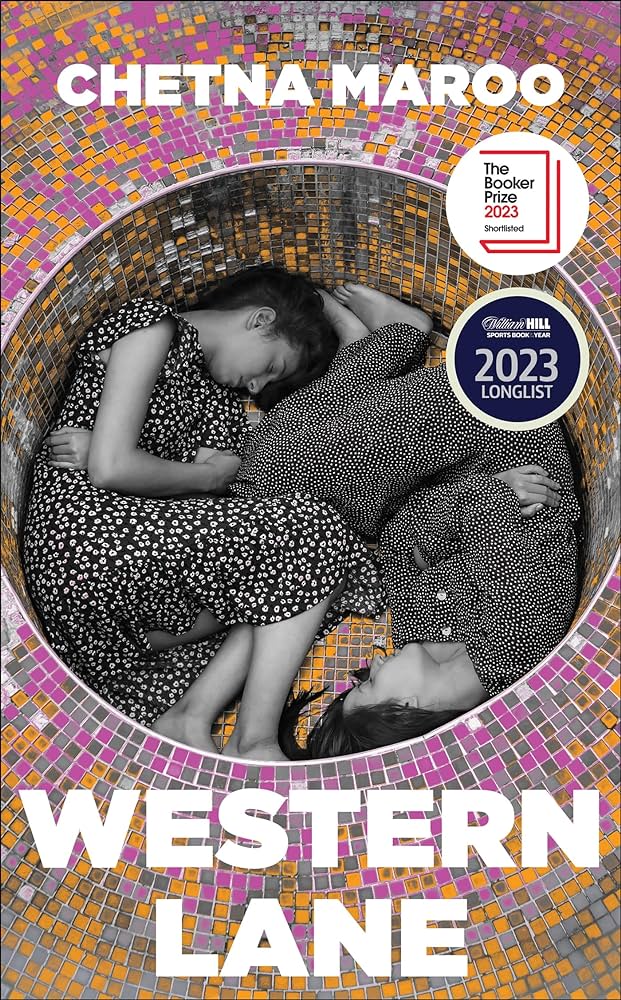

Western Lane is a short novel on squash and loss.

‘Western Lane,’ Chetna Maroo, Picador, 2023.

In this stupendous work of literature, loss thrives in all the spaces outside and inside a squash court. It echoes – at once, louder and quieter – with every strike at the ball. And it fills all gaps.

Chetna Maroo’s world in this Booker Shortlisted novel is squeezed out of a family of four somewhere unnamed in England – Pa, Mona, Kush and Gopi. The three girls are between 15 and 11 years old. Their mother, Charu, is newly dead in the novel.

In the space left by Charu enters the sport of squash, played by Gopi, who narrates the book. Gopi develops a romantic friendship with Ged. Ged’s mother runs the bar above the squash court, Western Lane. Uncle Pavan is a calm and tortured person. Aunt Ranjan is severe but also quiet and conservative. Maqsud is Pakistani and clearly the local squash advisor… The book has very few characters and most dance around the sport, doing very little and mostly observing things in their own time. Men, women, boys and girls are remembered with sighs, minuscule gestures and the shortest of sentences.

The result is startling and sweeping. It pushes the reader into herself, pulls a blanket over her and over the course of a mere 160 pages, almost chastens her. You emerge from the book thinking that everything that is not the bare and unspoken truth is immaterial to life and existence.

Which is not to say that the book has no frivolity or fun. Mona, Kush and Gopi are young girls, after all. But the book does them a giant service the way women writers writing girls can and often have.

For instance, it not only takes Gopi’s fierce understanding of squash seriously, it offers significant space to her to allow her to express her personal philosophy of the sport. What does it feel like to be alone in the T of the court? How do players think of throwaway advice on their game? There is a holiness associated with hearing sportspersons talk of their internal compulsions while playing – Maroo accords it all to her young protagonist. She raises her love for squash to a holy plane, positing as her inspiration one of the greatest in the sport, the real-life Pakistani hero Jahangir Khan.

No one allows young girls to speak this way – to have a sacred sense of seriousness over a world like sports which is quite abundantly occupied by men.

The book respects the unshorn grit that girls have, and also that essential teenage experience – of that gigantic internal churn when society, family and you yourself are pulling yourself in different directions. Here too, brevity is beautiful. With the overarching tool of grief, Maroo delves into that liminal state and offers the reader a bit of a revelation. Her technique is so sharp that it strikes you as otherworldly in a world of novels dealing in fantasy or sharp realism.

For a work of words, this story of an immigrant Gujarati Jain family has a lot of silences.

Maroo’s readers are sure to be familiar with the shattering quiet that occupies houses after deaths. But they may not be aware of how a novel can feast on this silence. The wordlessness is tyranny to the reader but to the inhabitants of the novel, it is necessary and calm, and as a result, almost stark in its beauty. Feelings pass from Gopi to Pa, from Kush to Pa, from Pa to Ged’s mom, from Gopi to Ged, from character to character, like notes are carried by instruments in a concerto.

Take this passage, for instance, where Pa is tired but it’s Gopi who speaks of it.

‘You can stop,’ he said.

He placed the racket gently on the floor. He looked so tired.

‘I’m tired,’ I said. My heart was beating hard.

‘I know.’

How can a work of art be so devoid of artifice? The reader is forced to wonder.

Western Lane is a triumph of the form of the novel while at once challenging the role it can play in representing realities otherwise familiar to its trope. That it is Maroo’s debut novel is a startling fact. Nowhere does the sanctity of her unique tone falter, there is nothing in the novel that is not deeply sacred to loss. And squash.