The Cholas and Why They Were Revived in Politics

The following is an excerpt from Lords of Earth and Sea by Anirudh Kanisetti, published on January 18, 2025 by Juggernaut Books.

Kaveri’s water gushed through mud canals, lapped at the walls of tanks. For century after century, it murmured the same humdrum story. On its banks, Tamil-speaking villagers lived out their lives. Their lands were owned by peasant clans in whose mud-and-thatch homes livestock bleated. Occasionally, a king showed up from another region and made gifts at a village’s little temple but they were mostly left alone. Sometimes they squabbled over water or herds. But otherwise, for centuries, little disturbed the ancient, uniquely self-governing rhythm of the Kaveri floodplain.

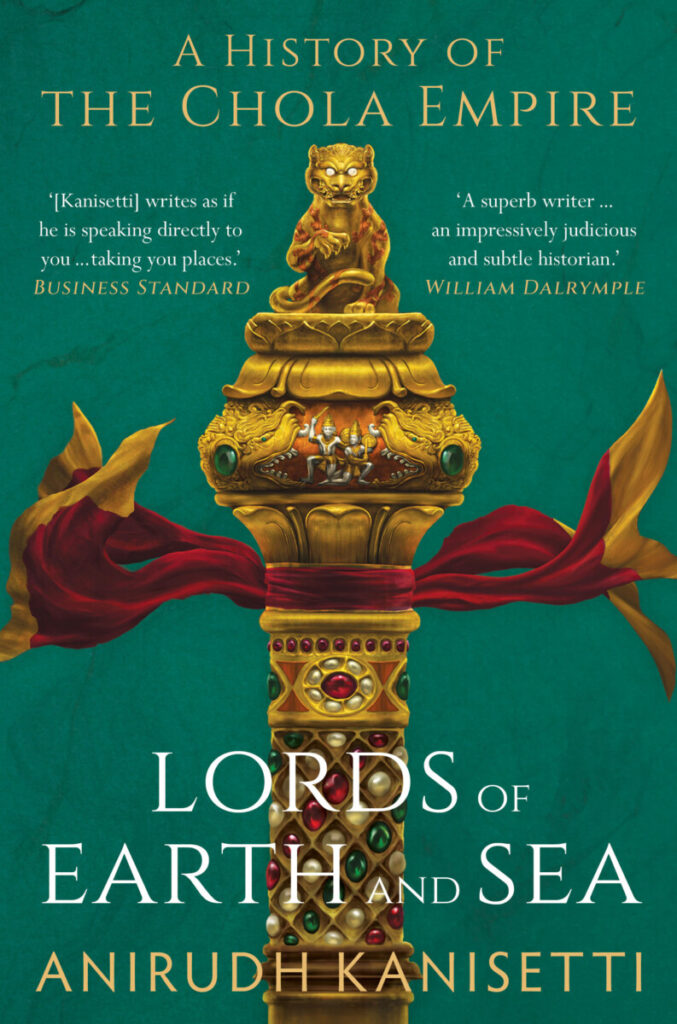

'Lords of Earth and Sea', Anirudh Kanisetti, Juggernaut, 2024.

But then something changed. More than a thousand years ago, around 850 CE, a peasant clan arose in the Kaveri floodplain, seemingly out of nowhere. First, they conquered villages. Then they raised armies, tens of thousands strong, and marched them up the Kaveri to conquer the warlike Deccan highlands. Merchant corporations kowtowed to them, following their conquests to bring these kings tribute of camphor and pearl, and to transport their armies across oceans. Their loyalists harnessed the great, lazy sway of the Kaveri, taming its delta, studding it with settlers. Their administrators funnelled hundreds of tonnes of granite, thousands of tonnes of golden rice into enormous new imperial temples. Glorious in plaster, paint, tile and gilding, two of these temples in particular stood out. These colossi were the tallest freestanding structures on Earth, excepting the Pyramids.

Both these temples – blazing with light from dozens of bronze idols, fragrant with offerings of sheep’s ghee and heaps of flowers – bore the name of this clan that arose from nowhere to conquer the world. Today we call them the Brihadishvara temples, the temples of the Great Lord Shiva. In their own time, they were called the temples of the Kings-of-Kings, men whose edicts, we are told, adorned the diadems of crowds of princes. These were the men of the imperial Chola dynasty – an unexpected superpower that changed the history of the planet.

The Cholas were unexpected for two reasons. For most of Indian history, the subcontinent has been dominated by either one of two great geopolitical regions: the Gangetic Plains, with its sprawling Maurya, Gupta, Tughlaq and Mughal empires, or the Deccan Plateau, with its warlike Satavahana, Rashtrakuta and Maratha empires.

Also read: Lessons from the Chozha Dynasty for Our Democracy in Decay

When the Cholas emerged onto the scene in the ninth century CE, the Rashtrakuta lords of the Deccan were acknowledged, even by foreign rulers like the Arabs, to be the subcontinent’s dominant rulers. The Cholas changed all that. They, for the first time, united the vast area of the Tamil and Telugu coasts, creating a Tamil-speaking empire that lasted nearly three hundred years – as long as the Mughal empire that came much later in North India. Through a series of spectacular campaigns, the Cholas not only humbled the Deccan Plateau but also raided as far north as Bengal and the river Ganga, symbolically subordinating all of South Asia to their imperial sceptre: the tiger-surmounted sengol you see on this book’s cover. It was the first and only time that a Tamil-speaking coastal polity lorded it over other proud, distinct regions of India.

Chola power was not contained to the boundaries of present-day India, either. They had a long-lasting outpost in Sri Lanka, and successfully raided the shores of the Malay peninsula, an expedition with no precedent in the Indian Ocean. They sent shockwaves all the way to East Asia. ‘The crown of the [Chola] ruler,’ wrote an eleventh century Chinese bureaucrat, ‘is decorated with luminous pearls and rare precious stones...He is often at war with various kingdoms of Western Heaven [India]. The kingdom has sixty thousand war elephants...There are almost 10,000 female servants, 3,000 of whom alternate everyday to serve at the court.’ Not bad for a family of humble origins.

There was another way in which Chola power was unexpected. They ruled the Kaveri floodplain, a region that had been settled by cultivators from the early centuries CE. For much of its existence, agrarian life there had little to do with kings or kingdoms. Divided up into a patchwork of 500 nadus, literally ‘countries’, villages in the Kaveri floodplain managed their affairs – irrigation, harvests, markets and tax revenues – autonomously, mostly through assemblies of kin. In the vast landscape of medieval India, this was pretty much the last place one would expect to see a powerful kingdom.

In global history, it is often the most fragmented regions that give rise to the grandest of polities. Greece, under Alexander the Great. Mongolia, under Genghis Khan. And the Tamil land, under the Cholas.

The Chola state was greatly feared and admired by its contemporaries. In the last century of the empire, and for two hundred years after, in Kongu, the hilly region between Kerala and Tamil Nadu; in Nellore and the Krishna-Godavari Delta in Andhra Pradesh, local dynasties claimed Chola names and titles and attempted to fashion themselves as new Cholas. As late as the sixteenth century, Malay kings were inventing family histories claiming descent from a near-mythical ‘Raja Chulan’ – a warped memory, perhaps, of the conqueror Rajendra Chola.

Yet, by the time the British established the Madras Presidency in the seventeenth century, historical memories of the Cholas had faded into South Asia’s endless tapestry of legend and myth. The names Rajaraja and Rajendra had been forgotten. The great imperial temples stood empty: communities only maintained their own local shrines. According to the distinguished Tamil historian, A.R. Venkatachalapathy, when the first Tamil steamship companies were established in the early twentieth century, no memory remained of the Cholas’ swashbuckling oceangoing expeditions.

Also read: Police Book Director Pa Ranjith for Saying Chola King's Rule Oppressed Dalits

This changed rapidly due to two movements: the Indian freedom struggle and, soon after, Dravidian nationalism. From the 1930s onwards, the great historian, K.A. Nilakantha Sastri, founder of South Indian historical studies, pored through thousands of Chola inscriptions and compiled a magisterial account of the dynasty. Sastri found in the Cholas, proud, warlike and confident rulers that seemed to express the highest political ideals of his time: constitutional monarchy coupled with local self-government.

Soon after, freedom fighter and author, Kalki R. Krishnamurthy, wrote the explosively successful Ponniyin Selvan, a fictionalised account of the rise of Rajaraja Chola, published in a monthly periodical. Krishnamurthy, according to his granddaughter and translator, Gowri Ramnarayan, intended for his fictional Chola clan to embody the personalities of various nationalist figures, in order to promote a sense of pride in both Tamil and Indian identity. ‘The Mahatma’s nobility, Nehru’s charisma, Patel’s steel, Rajaji’s integrity, and the compassion of Buddha and Ashoka.’

But in the decades after, as India’s federal structure came to favour Gangetic histories and the Hindi language, the new state of Tamil Nadu found a need for an alternative narrative: a narrative of Tamil glory, of a distinct, Tamil-led Dravidian identity. And the Cholas, with a sprawling empire, were the perfect emblems of this concept, inspiring blockbuster films such as Raja Raja Cholan (1973). In more recent decades, they have been claimed as Hindu nationalist icons, with a sengol, a Tamil royal sceptre, enshrined in India’s new Parliament building in 2023. And so the Cholas continue to ride history’s waves – forgotten once, then rediscovered and reimagined again.

Anirudh Kanisetti won the Sahitya Akademi's Yuva Puraskar for his book Lords of the Deccan: Southern India From Chalukyas To Cholas in 2023.

This article went live on January twentieth, two thousand twenty five, at zero minutes past eleven in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.