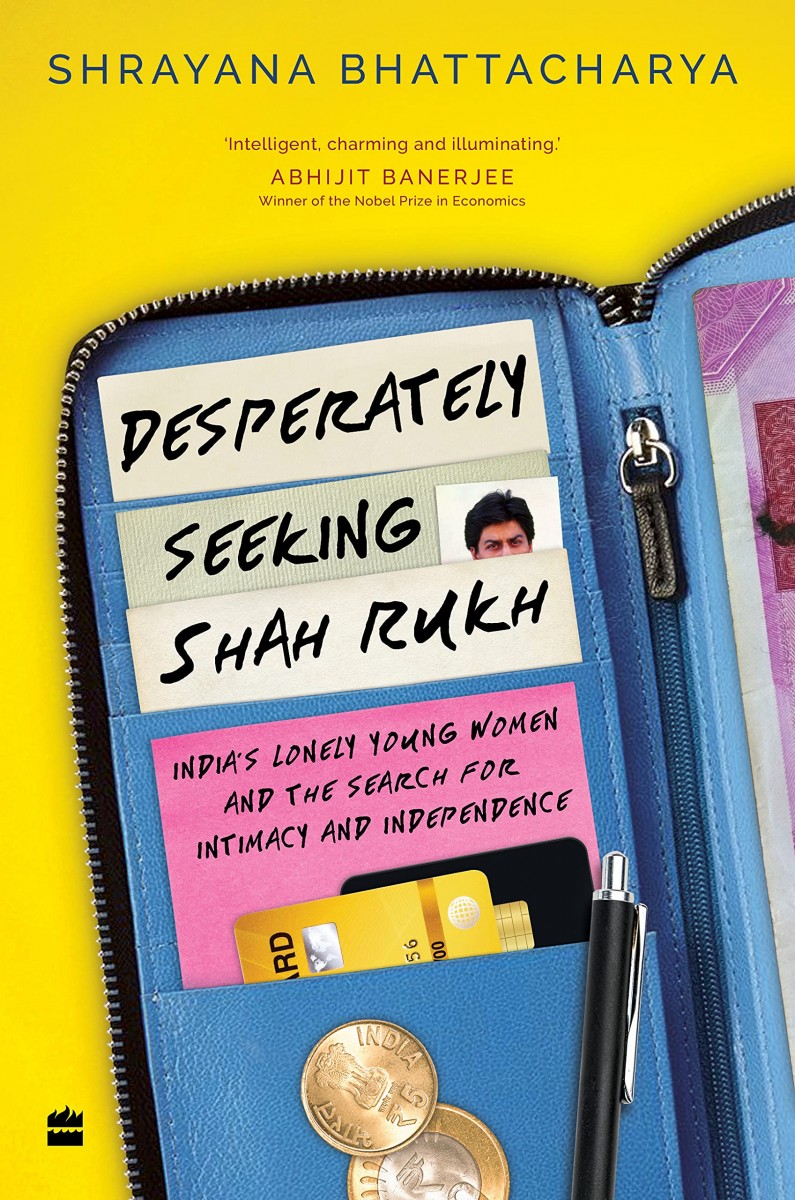

Book Review: In a Sea of Indian Men, Why Everyone Is Seeking Shah Rukh

As I read the first 20 pages of Shrayana Bhattacharya's book Desperately Seeking Shah Rukh, my mind went not to a Shah Rukh Khan film, but to a clip from Star Trek where William Shatner bellows out a long “Khaaaaaaaan”.

Shah Rukh Khan has been the bane of existence for a generation of men. It’s not that women compare you to Khan when you’re dating them, it’s just that you know in your heart that they’re comparing you to their favourite Khan role. They can’t help it. When things go south, you just know it’s his fault, and the fault of those damned expectations that he’s given them.

You get older and more jaded, and you think the man can have no further effect on your life. And there he was again – a friend gifted me this book, about how much his film roles and his public persona spoke to women’s souls. The indignity of reading about the ‘perfect’ man, along with the realisation of not measuring up, is enough to turn you into Shatner.

Also read: Book Excerpt: Dard-e-Disco

Shrayana Bhattacharya

Desperately Seeking Shah Rukh

HarperCollins, 2021

Desperately Seeking Shah Rukh is a sociological study, set around the fulcrum of the Khan personality and mythos. Khan, like any other big Indian star, is not an actor – he is a Hero. Actors play different roles. Heroes play themselves ad nauseam. Khan’s famous romantic roles from the Karan Johar and Yash Chopra oeuvre are essentially the same character. He is the sensitive, charming and kind man who rescues the woman in his life from the drudgery of her humdrum existence.

This is a direct contrast to the heroes of the 1970s and '80s, who were protectors and patriarchs rather than lovers. Many a character played by Sharmila Tagore, Zeenat Aman, Parveen Babi, et al would start the film wearing skirts and boozing, only for the hero to turn them into good Indian women by the end. She who had started the movie wearing revealing dresses would end the movie wearing a chaste sari. (Satyam Shivam Sundaram, I must hasten to add, remains a shining exception to this rule.) Imagine, then, the thrill of finding out this extremely intelligent man who was ready to cater to the female audience. Not, perhaps, since Rajesh Khanna was an actor so popular with women. Almost 25 years separated the Khanna heyday from that of Khan, and the women who experienced the latter are still infatuated with the man.

The personal experiences of the author, Bhattacharya, obviously a fan, provides the anchor for this study of Indian women. Khan is a unifying factor for women, Adivasi and Brahmin. The author is an accomplished economist and writer, choosing Khan as the constant for her study of Indian women, and to an extent men, born in the '80s and '90s. It goes beyond the anecdotal and evaluates its subjects utilising hard data as well. While Khan may be the constant, the variables are many – caste, class, geographical and occupational. The struggles of these women, divided by these variables, are of course very different from each other. Some seek personal fulfilment while others are just looking to make a living.

Also read: A Play About Gandhari – and About Gendered Roles Across Eras

Cinema provides a much-needed escape for the average Indian man from his rather harsh reality. For women, however, even the cinema is not easily accessible. The lack of an independent income and the physical threat implicit in a dark cinema hall, without any companion, are rather powerful factors that made the old cinemas very women unfriendly. Multiplexes improved on the safety aspect but only for people who could shell out a couple of hundred rupees for a ticket, even if you forget the atrociously priced popcorn. So when you are able to access the escapist fantasy provided by movies, you would obviously want the one that speaks to your soul.

Shrayana Bhattacharya. Photo: Twitter/Shrayana Bhattacharya

The way that women view and connect with Shah Rukh Khan provides insight into the anxieties experienced by them. I am not a literary reviewer, and there is no purpose to a clumsy literary analysis; more accomplished minds than mine can take on that task. However, I can fully endorse this work – it is deeply engaging, and as a reader, or at least a male one, will take your minds down many paths which you did not know existed. As an analysis of the world of 30-something metropolitan professionals, regardless of gender, it’s a therapeutic read. It’s just accurate.

The Shah Rukh Khan mythos started in the mid-1990s and is still going strong, even if every new release is not a monster hit. Khan is now in the news mostly for the attacks on him and his family. The myth is a dangerous one for the current ruling dispensation. It unifies what they want to divide. This man who flaunts his faith while maintaining an old-world air of accommodative secularism does not conform to the stereotype that they wish to assign to him.

A work as detailed as this would obviously have taken years to plan, research and to write. By luck or design, the book has released at a time when Khan has become more relevant than ever. The “idea of India” that is the site of all political contestation these days now incorporates the fate of Shah Rukh Khan as an unavoidable part of its own destiny.

Will Khan stay in India? Will he continue acting in films? Will he withdraw from public life? These are questions not only about Khan the person but about the trajectory that the country is on. Leaving one’s own imagined grievances with Khan aside, the man is rather uniquely placed to influence this country and society. We need people who can communicate charm, empathy and kindness. So, I say, Khan for PM. Why the hell not?

Sarim Naved is a Delhi-based lawyer.

This article went live on February eighth, two thousand twenty two, at zero minutes past twelve at noon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.