Circles of Freedom, Not Confinement: Feminist Street Theatre in 1970-80s India

Excerpted with permission from Deepti Priya Mehrotra's Walking Out, Speaking Up: Feminist Street Theatre in India, published by Zubaan.

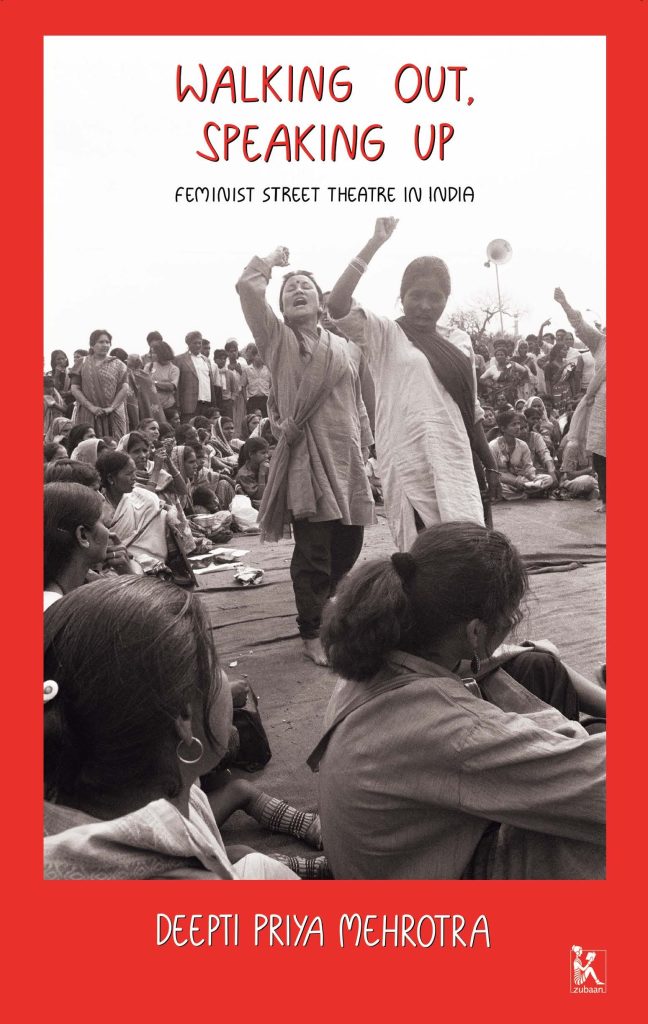

Theatre opened up elements of the personal, in public, for political ends. Mangai (2013: 45) comments that women’s street theatre of the 1970s and 80s was concentrated, euphoric and linked to the possibilities of action. In a sense, ‘being visible’ constituted a form of political action in itself. The sheer presence of groups of women, performing in the open, was startling; the street (as well as parks, marketplaces, police stations) were quintessential male spaces.

Arriving at a public spot, the actors would demarcate a circular performance space. Women have long been familiar with circles of confinement, a ‘lakshman rekha’ beyond which they cannot step, promising the illusion of safety. But here women were reinventing circles as spaces of freedom, from where they could step in and out. In Ehsaas, women expressly reclaimed the public realm, the wide world as it were, defying patriarchal diktats which tried to keep them within a ghera, circle, defining limits, enclosing and confining them.

A man (addressing women): Stay inside, further inside (andar, aur andar)! Hide away, do not show yourselves!

One woman (women jostle around, restless): Why?

Man: Because my gaze can harm you.

Second woman: Then why don’t you remain inside?

Man: To see that you don’t get out.

Third woman: What if we do?

Man: Stay inside!

Fourth woman (surges out): You harm us inside too! We will not stay! (Several women step out.)

Man (agitated): Hey, get back in!

All the women: No!

Man: Streets are male territory. You can’t move around here.

Fifth woman: Why is our coming here making you nervous?

Man: Why have you come into my area?

Sixth woman: The world is for everyone! (Duniya sabke liye hai!)

Man: Don’t know why they’ve come!

Women together (walking freely): To study, to learn, to see, to earn!

They head off in different directions—and the line of containment loses all meaning.

Deepti Priya Mehrotra

Walking Out, Speaking Up: Feminist Street Theatre in India

Zubaan, 2025

Plays like Ehsaas projected no unreal fantasy of easy liberation. But they affirmed the significance of women’s protests and acknowledged both private and public spheres as sites of conflict and contestation. Writing of the freedom struggle, Thapar-Björkert (2006) describes women in Kanpur and Aligarh locked up by families to prevent them from joining demonstrations; yet many managed to step out, join protests, distribute subversive literature. ‘At such moments of heightened political resistance, the street is seen as the site of righteous battle, with liberatory potential for both self and society.’ Once again, feminist theatre configured the streets as spaces for subversion, where intense conflicts were played out, compelling the audiences to engage and introspect. Anuradha Kapur recalls: ‘[M]any of us in Delhi did street theatre which was directly connected to visibilising issues. I, along with many women in Stree Sangharsh, dealt with rape laws and dowry problems and that was a very direct connection...’ (Subramanyam 2013b: 217). Kapur’s expertise was integral to making several feminist street plays, including Om Swaha.

At a workshop with women’s groups in North India, Seema, a member of Sakhi Kendra, a women’s group in Kanpur, improvised, playing the role of a submissive woman who is tortured by her alcoholic husband until she finally walks out. It was her own story; she wanted to tell it to the world, and the sequence got included in the play Gumraah. Seema shone as an actor, and was happiest when she performed in Pahlepur, her natal village, where she now worked to support other women.

Participants in feminist street theatre cut across class and caste: students, community workers, activists, teachers, homemakers and sundry others. Challenging the status quo, problematising gender, marriage and the patriarchal family helped prepare the ground for the open politics of sexuality, including the LGBTQ movement which developed subsequently in Delhi and elsewhere.

Also read: A Play About Gandhari – and About Gendered Roles Across Eras

Most participants understood patriarchy and capitalism as interlocking systems that reinforced one another. They were deeply concerned about economic inequality, and the class differences between women. At the same time, a collective politics was sought, emphasising women’s common issues, for instance around gender- based violence. The theatre, and indeed the women’s movement, was an attempt to listen to one another, and build a radical politics from the ground up.

Rati Bartholomew (in Seagull Theatre Quarterly 1997a: 44), who facilitated numerous women’s theatre workshops across the country, noted that there was tremendous sincerity and conviction amongst the participants. The theatre was sharply political, even when several participants were paid workers in non-governmental organisations (NGOs). That many women required some remuneration in no way undermined their contributions: it would otherwise have been impossible for them to engage regularly. Essentially, feminist theatre helped them to reflect deeply on their own lives and aspirations, and understand the social forces they were up against. It facilitated the development of closer personal bonds as well as an exposure to various social milieus. Ultimately, women participated in the theatre because they believed in it; they found that it enabled them to say what they wanted to.

Deepti Priya Mehrotra is a political scientist with trans-disciplinary interests. She has engaged with street theatre and the women’s movement since the late 1970s.

This article went live on August twenty-eighth, two thousand twenty five, at fifty-five minutes past eleven in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.