She finds herself thinking, again, about Sanjit. She had thought he would flourish after leaving the Daily Telegram. With the coming of the free market, a media boom was on. New magazines and websites everywhere, with bigger salaries and snappy editorial designations, money flowing in endlessly as India became, briefly, one of the great investment destinations of the world, as Indian businesses that had made vast profits in natural gas, mining and real estate began expanding into media.

She herself did well for a while in that milieu, poached by a monthly as a feature writer, and where, on her first day at the new job, her former boss from the Daily Telegram called to tell her that the American consulting firm McKinsey had been asking about her. He sounded half impressed, half envious, saying that he had managed to scare them off by telling them about her lefty credentials.

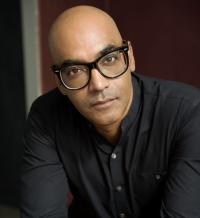

Siddhartha Deb

The Light at the End of the World

Westland Books (May 2023)

Yet Sanjit, during that boom time, moved uneasily from one job to another, on a trajectory that led ever downward. Fired from a weekly for being too critical of the Hindu right, resigning from another in solidarity with a junior staffer accusing the editor, a liberal icon and a great critic of the Hindu right, of sexual harassment. At drunken evenings in the Press Club or in dim bars smelling of cheap Australian lager, people complained to Bibi about his abrasive personality. He was too critical of India, of capitalism, people said. Embittered by failure, out of sync with the times. Others complained that he was shockingly unfriendly, so antisocial that even when he bothered to show up at a party at someone’s house, he simply stuffed himself with the food on offer, drank copious amounts of other people’s liquor and left without so much as cracking a smile.

For a while, he worked at an old, rationalist magazine, fusty, pre-liberalisation, a place where the office clerks took long, post-lunch naps at their desks and everything moved at a snail’s pace but that was nevertheless a last refuge for people who still wanted to be anti-establishment reporters. When that shut down, sinking under the weight of civil and criminal defamation lawsuits filed at tiny provincial courts by men with small, modest businesses – men who nevertheless had unusually vast sums of money and swanky metropolitan lawyers at their disposal – Sanjit moved across the river, to Trans-Yamuna Delhi.

He became the sole employee of an internet site run out of a middle-class flat in a DDA housing complex, one of hundreds of thousands of such buildings erected by the Delhi Development Authority in the days of central planning. The site was funded by a retired civil servant with his savings. The man wrote what he himself admitted was a contradiction in terms, progressive Hindi fiction, his stories often involving gay characters who were, unusually, not portrayed as deviants.

Then, Sanjit published a piece on the suspicious suicide of an army officer in Assam. The young captain’s conscience had been pricked after taking part in an operation involving seven undocumented Bangladeshi migrants, men led to believe by an Indian fixer that they had been hired as day labourers and that they were being driven to a field at three in the morning because they were expected to begin work very early. The captain and his men had been waiting for the migrants, confused, docile creatures who lined up as asked to and were quiet as a soldier stood behind each one. The gunshots were almost simultaneous. It took far longer to dress the corpses in camouflage and plant AK-47s on them. A dead undocumented was worth nothing, but a dead terrorist was worth five points. The unit had been short by thirty-five of the three hundred points they needed to claim a bonus and a lucrative posting with a United Nations peacekeeping mission in Haiti.

Soon after, the captain gave an interview to the press with details of the execution. He was suffering moral pangs because the unit had trouble counting the bodies, there always appearing to be one more or one less than the seven undocumented they had killed. The executions had had been all about numbers, nothing personal or ideological to it at all, and yet it was the numbers screwing them over. Even the photos they sent to HQ refused to be definitive, the bodies in the pictures never totalling up to seven. A day after the interview, the captain was hospitalised by the army for depression. He hung himself on the very first night of his stay in the military hospital. No one other than Sanjit believed that the suicide might have something to do with his statement about the fake counter-insurgency op. A week after the story was published, the retired civil servant was run down at a roadside crossing by a truck that came from nowhere.

Siddhartha Deb. Photo: Twitter/@debhartha

After that, Sanjit lived a nomad’s life, cobbling together assignments from India and abroad. He became like a ronin from the Japanese films he loved to watch, an unwashed, unshaven samurai with a bamboo sword in his scabbard, writing ever more complicated conspiracy stories that looped around the Gujarat mass murders of 2002 and the US global war on terror after 9/11. The pieces strung together surveillance, extra-judicial executions and witnesses turned rogue, his conclusions pointing ever upward, ever inward, to the seats of power, to the alliance between entrepreneurialism, electoral politics and militarism. Sometimes, as when he turned his sights on the past, digging up odd factoids about right-wing cult figures like Vinayak Savarkar and P.N. Oak, he sounded almost demented, unfazed by the torrents of abuse coming his way on social media and the periodic suspension of his accounts. Then, finally, silence while on a trip to the Northeast that involved looking into the deaths of four young Manipuri men who had iron nails hammered into their heads and hands before being executed at close range, their killers, a counter-insurgency unit consisting of seven men and a woman officer, recommended for Shaurya Chakra medals to be handed out at the Republic Day parade in Delhi, in front of the new parliamentary complex.

Excerpted with permission of Westland Books from The Light at the End of the World by Siddhartha Deb.