‘Aapa Jaan’, a Biography of a German Lady Who Diligently Served the Jamia Community

Unlike most qabristans (Muslim graveyards) across India, the Jamia Qabristan is unique in the sense that one can find several non-Muslims buried there. Situated besides Jamia Schools, this small and shady graveyard is the last resting place of the many makers of Jamia Millia Islamia — the teachers and staff members of the university. Most of the people buried here are not blood relatives, yet it is still considered to be a family graveyard in the sense that they were all a part of the larger family called the Jamia Biradari, fraternity or family. Almost a century old, the most prominent qabr (grave) here today is that of Gerda Philipsborn. The inscription in Urdu reads as under:

na hoga yak-bayaban mandgi se zauq kam mera

habab-e-mauja-e-raftaar hai naqsh-e-qadam mera

From a whole desertful of fatigue, my relish/pleasure will not be less/little

My footprint is a bubble of a wave of movement

Beneath this couplet of Mirza Ghalib, translated by Frances W. Pritchett, it says:

Gerda Philipsborn “Aapajaan” (April 30, 1895-April 14, 1943)

Served Jamia Millia Islamia from January 1, 1933 to April 14,1943.

Gerda Philipsborn's grave in the Jamia Qabristan. Photo: Mahtab Alam

It is not that Philipsborn is completely unknown to the people of Jamia as at least two facilities in the university are named after her – the Gerda Philipsborn Day Care Centre and the Gerda Philipsborn Hostel. In 1995, a short biography in Urdu titled Bachchon Ki Aapa Jaan: Gerda Philipsborn was published by Jamia Maktaba, the publication division of the university. But, not much was known about who Philipsborn was before she arrived in Jamia. How did she end up working in Jamia or why did she choose Jamia over any other place? What were her motivations ? Was it just an escape from Nazi Germany or was there something beyond that? And above all, how did a German Jew, whose life was quite different from most of the students, teachers and staff members there, not only became an integral part of the Jamia Biradari, but also acquire the status of Aapa Jaan or the beloved elder?

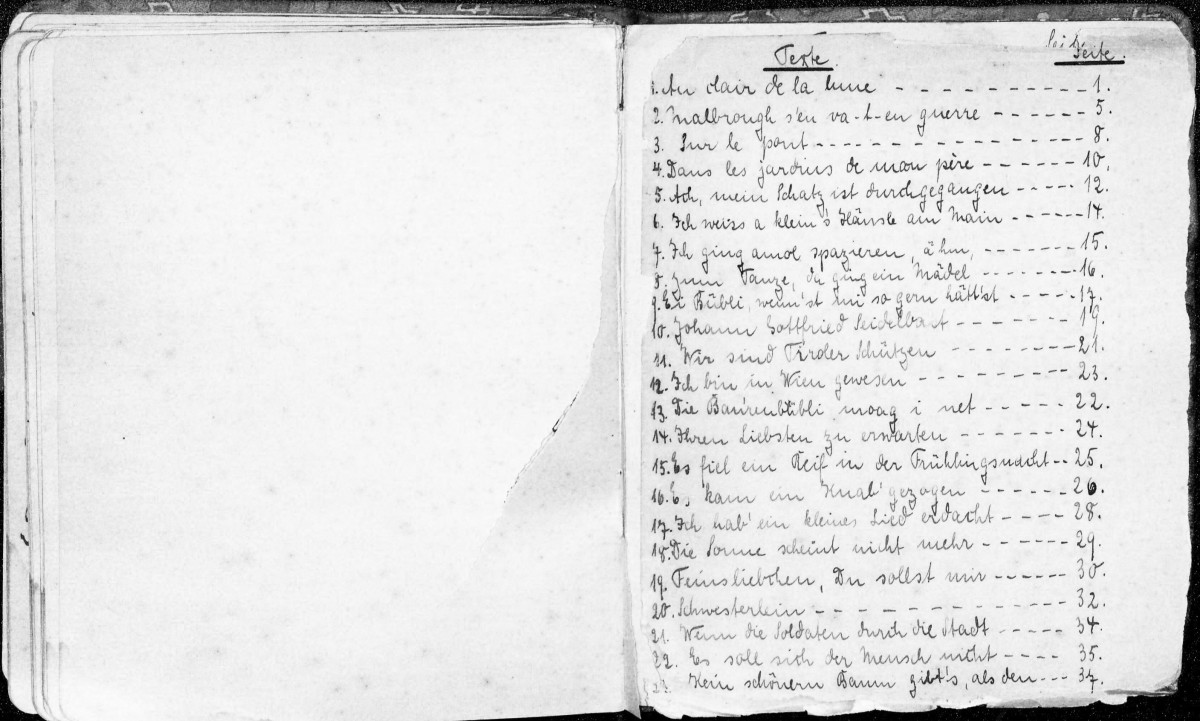

Gerda’s handwritten songbook, Mujeeb papers, courtesy family of Muhammad Mujeeb.

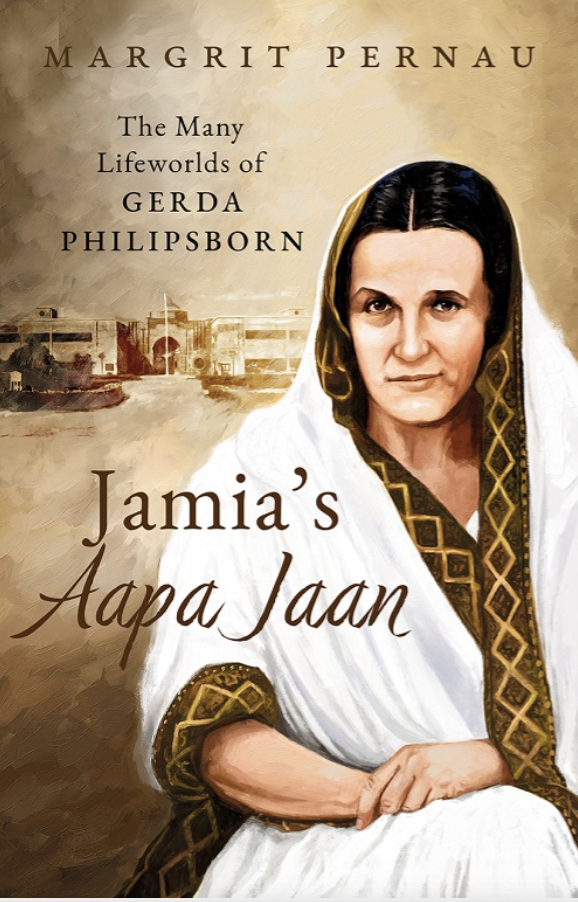

In this engrossing biography of Philipsborn, Dr. Margrit Pernau, a longtime researcher on Jamia and a professor at the Freie Universität Berlin, Germany, not only provides answers to some of the unanswered questions for the first time, but in doing so she takes the readers on a journey to the early years of Jamia and Germany of that time, apart from uncovering the many lifeworlds of Philipsborn and throwing light on the trials and tribulations of the university in that period. However, Jamia’s Aapa Jaan is not a conventional biography in the sense that it does not solely rely on the known facts about the subject. It heavily relies on emotions and the author is placed to do that as a scholar on the history of emotions.

“Gerda moved through many different worlds in her short life. Recreating these lifeworlds needs more than consideration of words and ideas,” writes Pernau, adding “We need to pay attention not only to what she said and wrote (or what was written about her), but also what she heard…”. According to the author, there is a need to hear the sound of an aria of a Wanger opera that she sang, or more often, listened to, the melody of a Jewish folk song that she learned to perform, the German songs from her childhood that she recalled in Delhi and taught to the little children of Jamia. Hence, the entire book is organised according to emotions, each chapter taking up a particular emotion.

Margrit Pernau,

Jamia's Aapa Jaan: The Many Lifeworlds of Gerda Philipsborn,

Speaking Tiger, New Delhi (2024)

And this, the author notes, is “not because it is the only one that Gerda would have felt, nor even because an emotion can ever successfully be separated from all the others that surround it and impart their colour and smell, their rang-o-bu, to it. Still, placing one emotion at the centre allows us to capture the atmosphere of a particular phase in her life.” Divided into 11 main chapters, the book covers different phases of Philipsborn's life and works, starting with the feeling of 'Comfort and Security', a childhood in the Kaiserreich and ending with the emotion of 'Outer War and Inner Peace', detailing her final years.

The author informs us that Philipsborn gave up her life in Germany in 1932, even before the Nazis came to power and forced Jews, who could afford to and had the necessary contacts, into emigration. Born into a rich, Jewish trading family, Philipsborn had all the freedom to choose a career, be that as an opera singer or as a kindergarten worker, the freedom to choose her partner in life or even to not marry, to invite male guests to her family home and to explore new forms of friendship, across gender and race. However, adds Pernau, “for Gerda, freedom was not a licence to do whatever she wanted, but increasingly meant the freedom to choose the cause that she wanted to serve and devote her life to, as part of a community of like minded men and women.”

According to the author, like so many in her generation, she dreamt of a new world of equality and justice, in which both the deadweight of tradition and the sufferings of modernity would be overcome. “This dream echoed across the continents and was the basis of the friendship that linked her to Zakir Hussain, Muhammad Mujeeb and Abid Hussain,” three prominent makers of the university. “Jamia and its children became not only the cause that she freely chose, but also the family that accepted her and made her one of their own – Aapa Jaan, the beloved elder sister, not only of the children but increasingly of the entire biradari,” concludes Pernau.

Gerda first met Zakir Hussain, Muhammad Mujeeb and Abid Hussain at a party in Berlin in late 1924 or early 1925, hosted by Suhasini Chattopadhyay (the younger sister of Sarojini Naidu) and her husband A. C. N. Nambiar, a journalist and political activist. Pernau reproduces an excerpt from Mujeeb’s biography of Hussain recounting their first meeting and the beginning of a life long friendship with Philipsborn:

“Very helpful in enabling Zakir Husain to find his way into the spheres of intellectual and cultural activity other than the university, was Gerda Philipsborn. We met her first at one of the evening parties that Mrs Nambiar … used to arrange to bring the right kind of Germans and Indians together. Then Mrs Nambiar stopped giving her parties and our social life became a blank... 'Why should I not ring up Fräulein Philipsborn?' [Zakir Husain] asked me. 'Do you think we know her well enough,' I replied. 'We'll see.' Immediately he took up the phone and rang her up. She was at home and said she would be happy to meet him. This was the beginning of a friendship whose depth no one could fathom.”

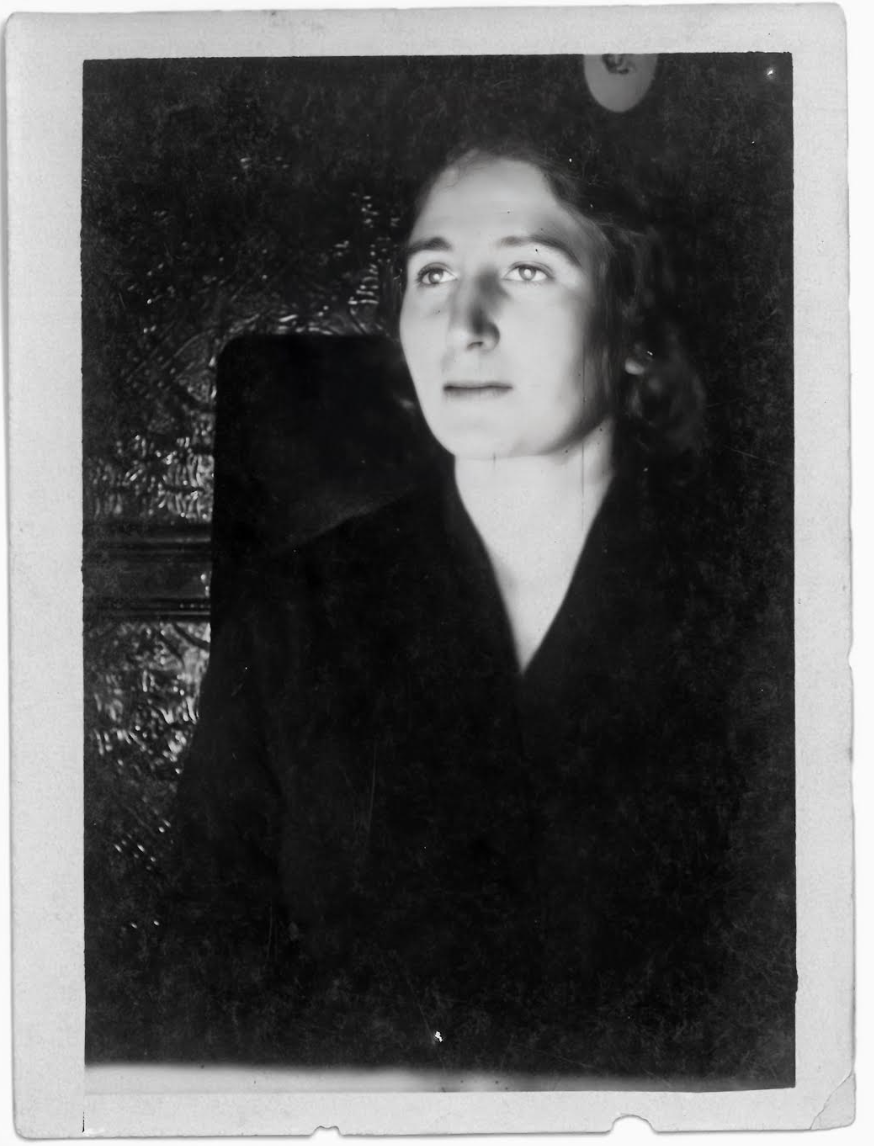

Gerda, last known image, Mujeeb papers, courtesy family of Muhammad Mujeeb.

The trio returned to India in 1926 and threw themselves into working for Jamia and making it a viable institution. “Gerda and Zakir Hussain stayed in touch, if one is to believe the editor of the journal Jamia, though the letters they wrote to each other have yet to be traced,” writes Pernau. Philipsborn joined her friends in Delhi in 1932 and they worked together till she died in 1943, barring the one year when she was arrested by the then Government of India as a measure against enemy aliens in British India, and was lodged at the parole centre of Purandar Fort, near Maharashtra's Pune. According to the author, on November 5, 1940, shortly after being brought to Purandar, Philipsborn wrote to her cousin, Lady Reading, not to plead her own case, but that of all the Jewish refugees.

Meanwhile, Philipsborn was very sad about her separation from Jamia. An excerpt from Payam-e-Talim (Children’s Magazine published by Jamia) of September 1940, reproduced in the book reads:

“…our Aapa Jaan will be separated from us for some time. She is very sad about parting from the children of the Jamia and her dear Payamis. Until the end of the fighting, she has to remain near Pune, but she will return afterwards. She has asked me to take up her work for the Payam-e Biradari with enthusiasm and keep the tree green in her absence. She also promised to write beautiful articles for the Payam-e Ta'lim in her free time.”

The book also informs us that during the first weeks and months at Jamia, Philipsborn believed that her hopes and the dreams that she had pursued for so many years would come true. According to Pernau, she adapted to Indian life as best as she could, but she also thought it was important to show the children of the world outside, something that the leaders of Jamia profoundly agreed with. “What helped her most in this development was her work as the warden (probably rather one of the wardens) of Khaksar Manzil, the hostel for the smallest children. Here it mattered less than at school that her Urdu still was far from perfect, though she seems to have picked it up quickly,” notes the author. In 1937, she had applied for naturalisation of her citizenship. While it was acknowledged by the police that she had not taken any active part in politics, but because of her connection with Jamia and the fact that she also wore khaddar, her application was rejected.

What is important to note is that Philipsborn's life in Jamia was not as smooth and easy as it may sound to have been. She had to face her share of difficulties despite best efforts from all the sides. “Even with patience and tactfulness on all sides, it took time for her to integrate into the Jamia biradari, a brotherhood that followed its own rules. The first personality clash pitted her against Abdul Ghaffar Mudholi, who was responsible for the primary school, including the coordination of all the teachers’ duties, thus formally her superior,” notes the author in the chapter titled 'Love and Care'. Mudholi was a strict disciplinarian and abhorred lack of punctuality, no matter who was late or for what reason. The author recounts an incident where Mudholi once invited Zakir Hussain to a meeting, but started it without him when the vice chancellor was running late. Upon his arrival, Hussain took it with good grace and a smile, and later admitted that it was Mudholi who taught him punctuality.

On the other hand, while Philipsborn had always passionately worked for causes that caught her imagination, she lacked punctuality. “It was not that she was lazy or did not care,” writes Pernau adding “but she was used to setting her own priorities.” The author further informs us that for this, she was admonished by Mudholi and when this did not change her attitude, he started writing formal letters of complaint to Hussain. According to the author, Mudholi’s annoyance can be seen even in the history of the primary school he would later write.

However, what is also important to note is that with time they learned to smile off their differences and to gently joke about them. Most interestingly, informs the author, when Mudholi fell ill, it was Philipsborn who took care of him and became the disciplinarian, enforcing strict dietary rules. “She refused to let him eat the khichri he craved and scolded him for behaving like a stubborn child. He would respond that it was she who was the stubborn sister. With the years, and with much patience on both sides, she indeed grew into her role as Jamia’s Aapa Jaan,” documents Pernau.

Like the example above, the book uncovers several other complex and complicated stories about the many lifeworlds of Gerda Philipsborn and Jamia. And it is done so magnificently and empathetically that one cannot think of a better book about the person and the institution she served until her last breath.

This article went live on August twenty-second, two thousand twenty four, at twenty-two minutes past six in the evening.

The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.