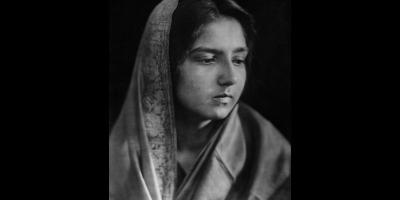

Excerpted with permission from Circles of Freedom: Friendship, Love and Loyalty in The Indian National Struggle by T.C.A. Raghavan, published by Juggernaut. The book looks at the national movement from the point of view of characters seen as more ‘marginal’, and explores through their stories and their relationships with each other, issues such as women’s lives in that period, the paradox of the liberal moderate Muslim, the impact the freedom movement had on marriages, and perhaps most importantly what the Independence movement looked like for people with a ring-side view of it but who weren’t at its centre. The following extract is about Aruna Asaf Ali’s marriage with Asaf Ali.

Outrage and criticism apart, the marriage [between Aruna Gangulee and Asaf Ali] faced other more personal hurdles before it found its balance. Asaf ’s ancestral house in Kucha Chelan may well have appeared primitive to young Aruna, brought up with more modern Western conveniences. On returning from England Asaf himself had had difficulties readjusting to living there. How would Aruna, with her convent school education and anglicized Bengali family background, cope with daily life deep in the by-lanes of the old city? She later recollected: ‘When I first came to live in Delhi after my marriage in September 1928, I belonged to an entirely different hybrid Anglo Indianized background. There I found it difficult to fit into a Muslim Indian way of living, hoary with customary manners and traditions.’ She is described as being ‘shaken’ by the ‘kitchen bound domesticity and seclusion of women’ and believed to have said later, only half seriously perhaps, that had she known what life in a typical Muslim home was like, she would not have married Asaf Ali!

T.C.A. Raghavan

Circles of Freedom: Friendship, Love and Loyalty in The Indian National Struggle

Juggernaut, 2024

The nineteen-year-old showed a lot of determination and staying power. She did not accept Asaf ’s offer that they move out of Kucha Chelan to a modern flat as that would have left his mother bereft. ‘Special toilet arrangements were made for her, and it was accepted that the customary observance of seclusion would not apply in her case.’ Aruna settled down in the old haveli – amidst ‘open drains running alongside the congested streets’ – initially managing as well as she could and then settling down to become a member of its community. But it was also apparent to her that the twenty-year age difference with her husband and her own youth meant that the transition to being the wife of a public figure would not be an easy one. In her recollection, in the early days after the marriage, ‘I was almost in purdah . . . not that my husband believed in it, but I just felt shy. I felt, oh, I would be abused, rather I seemed to have put my foot into something for which I was not prepared.’

We get a sense of her diffidence and awkwardness when, a little after the wedding, the couple was invited to a dinner party by a senior civil servant, Brijlal Nehru, at his residence in New Delhi (called ‘Lutyens Delhi’ today). Brijlal was a nephew of Motilal Nehru; the occasion was that Motilal was in town and Jawaharlal would also be joining them for dinner. Brijlal’s wife Rameshwari Nehru was active in women’s issues and later would also be active in Gandhian efforts to work with Dalits. Despite her husband’s career in the civil service, she was drawn to nationalism and was arrested in the 1940s during the Quit India movement. Towards the end of her life Rameshwari would be head of the Harijan Sevak Sangh, one of the important Congress organizations. All this was in the future, however; in the winter of 1928 at the time of the dinner party, Brijlal Nehru had recently been posted to the capital city and Rameshwari had thrown herself into social work and established the Delhi Women’s League to this end.

Asaf was acquainted with Motilal because both were practising lawyers and their common involvement in the Congress had drawn them closer together. As we had seen, Motilal was a supporter of Asaf ’s failed bid to get elected to the Central Legislative Assembly and had taken his defeat as a political setback for himself. Motilal was a leading ‘Swarajist’ and Asaf was part of the large group that supported his view that the Congress should supplement its agitational and protest activity with participation in the legislative bodies set up by the colonial state even if they had only limited mandates. That Asaf would be invited for a private dinner for Motilal was therefore not surprising. Yet the evening in Brijlal Nehru’s bungalow had, in Aruna’s memory, a subtext: ‘the establishment Nehru’ had invited the Asaf Alis because their ‘seditious clansmen from Allahabad were visiting’. Motilal and Jawaharlal were obviously the ‘seditious clansmen’.

The communal situation in Delhi and the rest of the country was, especially with Asaf present, an obvious conversation point. But there would have been others. Much, if not all, of this was way beyond Aruna; she recollected later: ‘I felt lost in what struck me as a sombre gathering of elderly persons talking about the problems of the day of which I was utterly ignorant.’ Jawaharlal arrived late, coming straight from a speaking tour in the Punjab ‘all covered in dust’ and Aruna was ‘dazzled by the first, close look of him’. She also recalled that ‘he looked me up and down with amused curiosity’; she ‘was wearing a silk sari and some jewellry [sic] – a dolled up slip of a girl destined to decorate drawing rooms’.

T.C.A. Raghavan is a former Indian High Commissioner to Pakistan.