Baijayanti Roy’s The Nazi Study of India & Indian Anti-Colonialism: Knowledge Providers and Propagandists in the ‘Third Reich’ (2024) rightly claims to be the first monograph-length systematic study of the trajectory of Indology under National Socialism (Nazism).

However, this is an understatement, for it is much more than that. It is a ground-breaking piece of research with a wealth of information that sheds light on so many things that we were hardly aware of. The monograph is the outcome of a three-year-research-project titled ‘Indology in National Socialist Germany’ conducted at Goethe University with support from the German Research Foundation. The title of the book, different from that of the research project it is the product of, indicates that the research conducted from 2018 to 2021 acquired a much wider scope, going beyond Indology to include not just the Nazi study of ancient but modern India as well.

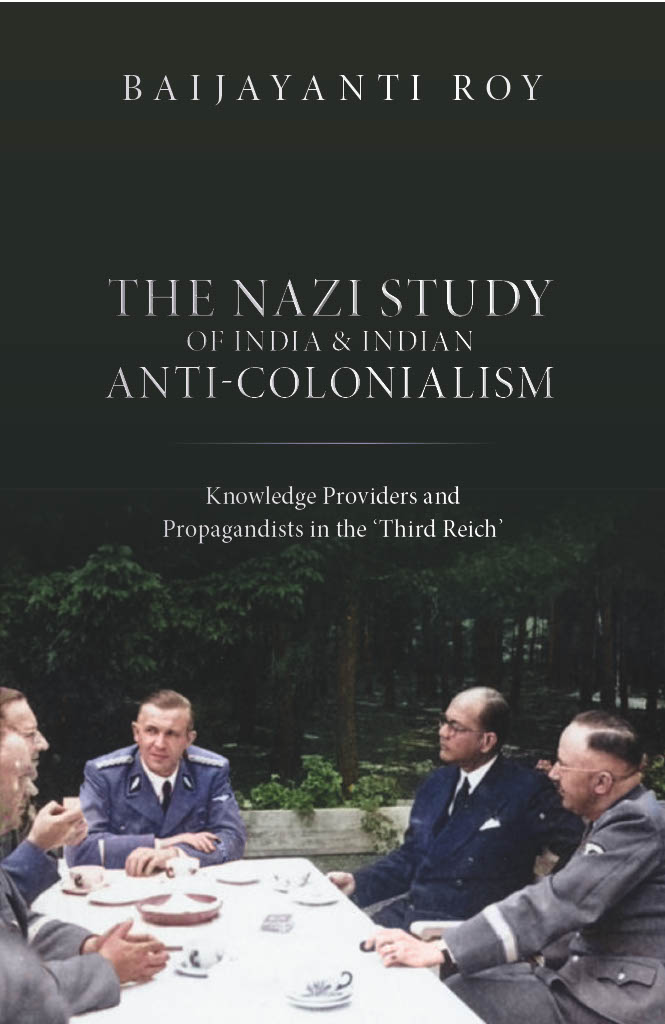

The Nazi Study of India and Indian Anti-Colonialism: Knowledge Providers and Propagandists in the ‘Third Reich’, by Baijayanti Roy, published by Oxford University Press (Oxford), 2024.

Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke wrote a biography of Savitri Devi Mukherjee née Maximiani Julia Portas (1905-1982), a Nazi spy, propagandist and a Holocaust denier, titled Hitler’s Priestess: Savitri Devi, the Hindu-Aryan Myth, and Neo-Nazism (1998). Marzia Casolari in her monograph In the Shadow of the Swastika: The Relationships between Indian Radical Nationalism, Italian Fascism and Nazism (2020) studied the connections between Marathi Hindu nationalism and fascism and explored contacts between fascists and Bengali nationalist circles. Vaibhav Purandare’s book Hitler and India: The untold story of his hatred for the country and its people (2021) presented a portrait and analysis of Hitler’s outlook on India and Indians, their culture and civilisation, and their struggle against the British colonial rule. However, Roy’s book is the first to focus on knowledge production on India in Nazi Germany and the propaganda the Nazis spread in India.

How the Nazis used the Bhagavad Gita

The 224-page-book focuses its attention on four organisations devoted to the dissemination of National Socialist ideology in India with the aim of influencing and inciting the Indians to rebel against the British. Divided into four chapters – excluding the introduction and the conclusion – with a chapter dedicated to each of those four organisations, the book probes how both scholars, including Indologists, as well as non-academic ‘India’ experts and some Indian anti-colonial intellectuals utilised “knowledge pertaining to India’s modern history and contemporary politics” for the fulfilment of “certain political goals of Nazi Germany”.

These are: the India Institute of the Deutsche Akademie (DA or German Academy), antecedent of the modern Goethe Institute, also known as Max Mueller Bhawan in India; The Sonderreferat Indien (SRI) or Special Department India (established in May 1941 under the auspices of the foreign ministry); The Oriental Seminar of Berlin (established in 1887) and its successors, the Ausland Hochschule or Academy for the Study of Foreign Countries (established in 1936), the faculty for the ‘Study of Foreign Countries’ (Auslandswissenschaftlichen Fakultat) at the University of Berlin and DAWI (Deutsches Auslandswissenschaftliches Institut), both established in 1940. And the final one is ‘Indian Legion’, also known as Tiger Legion, jointly formed by Subhas Chandra Bose (1897-1945) and the Wehrmacht (the German Armed Forces).

Roy makes excellent use of the archival material held at the major archives in Germany, India and the United Kingdom in her investigation of how some 19th-century German scholars contributed to the Aryan discourse by “appropriating India’s ancient past and excluding Indians from it” and how the Nazis engaged with ‘strategic’ knowledge of modern India. Conscious of the questionable nature of some of the surveillance records, she has attempted to corroborate them with primary and secondary literature. The primary literature referred here consists of the writings of different propagandists, which reflect the political engagements of the “knowledge providers”.

Also read: ‘Pandit’ Bhatta: From Scholarship Holder to Nazi Publicist

Roy points out how the Nazis abused the Bhagavad Gita as a means in their attempt to inspire the SS to fulfil its genocidal aspirations. In this pursuit Nazi propagandist Jakob Wilhelm Hauer’s booklet ‘Indo-Aryan Metaphysics in Combat and Deed: The Bhagavad-Gita in New Light’ (1934) came handy. The booklet claimed that the combative ethos of the SS found echo in the ancient Hindu text’s celebration of the Nordic Aryan ideals such as “the duty of the warrior to fight for honour and for the ‘Reich’”. It is said that Heinrich Himmler (1900-1945), one of the chief architects of the Holocaust, depended on this book to quote from the Bhagavad Gita.

Roy’s brings to light the close ties that Hindu revivalist movements such as the Arya Samaj and the Gaudiya order and Hindu nationalist organisations such as the Hindu Mahasabha developed with the Nazis.

Ernst Georg Schulze (1908–1977), a German disciple of Swami B.H. (Bhakto Hriday), born Narendra Nath Mukherjee (1901-1982), who took up the name Sadananda Brahmachari upon joining the Gaudiya order, followed his guru to India in 1935. In India, Schulze (Brahmachari) used the Gaudiya mission temples as ‘contact zones’ for those belonging to the Nazi network, among both Germans and Indians, and came to be suspected by the British surveillance of propagating National Socialism among educated Indians under the veil of religious activities.

According to the British surveillance reports, as noted by Roy, the Nazis communicated with Hindus primarily through the Arya Samaj. The commonalities of Ariosophy with eugenics and emphasis on authoritarianism and majoritarianism, emerged as the grounds for mutual admiration between the Nazis and the Arya Samajis.

An outcome of the collaboration between the Arya Samaj, the India Institute and the Nazi network in India was a scholarship in 1934. The scholarship, sponsored by the Institute and the firm Allianz and Stuttgarter, was awarded to Satanketu Vidyalankar, a History professor at Gurukul University, which had been founded by the Arya Samaj. According to a surveillance report from 1939, while collecting nominations for a scholarship in philology in Germany, the German consulate in Calcutta (now Kolkata) showed preference for candidates who were Arya Samaji or subscribed to the ‘Aryan world view’. Repeated instances of Arya Samaj pracharaks (preachers) praising Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) and National Socialism were also noted by the colonial surveillance. Roy highlights how the Nazis felt affinity with Hindu ethno-religious nationalism, which, in any case, had drawn inspiration from fascism and Nazism.

Also read: Burning Books and The Nazification of Literature

The Islamophobia prevalent in a branch of German Indology seems to have been imbibed by the Indologist Ludwig Alsdorf (1904-1978), a prominent Nazi propagandist. Roy suspects that this made Alsdorf sympathetic towards the Hindu Mahasabha, which subscribed to certain tenets of the European Orientalist worldview, such as Ariosophy and the perception of Vedic Aryans as progenitors of modern Hindus combined with intolerance towards Muslims, who unlike the Hindus, could not claim Aryan origin, according to them.

A field for Nazi and British spies

The India of 1930s turned into a field for Nazi and British spy networks. The book helps us enormously in understanding the genesis of the curious case of the overwhelming admiration for Adolf Hitler in contemporary India. We come across Hermann Beythan (1875-1945), an ex-missionary of the Evangelical Lutheran Mission of Leipzig, which had a base in southern India since the mid-nineteenth century. Beythan was resident there from 1902 to 1909, during which he mastered the Tamil language, both classical and colloquial. In 1934, he joined the National Socialist Teachers Association or NSLB, and went on to publish in 1936 a paean in Tamil to the supposed genius and achievements of Adolf Hitler, referring to him as ‘Mahatma’ or ‘the great soul’. Titled Who is Hitler?: Victory of Strength. It was published with financial assistance from the German Foreign Ministry and the Ministry of Propaganda with the objective of countering the growing Bolshevik influence in Tamil Nadu where biographies of Marx and Lenin were easily available in Tamil. The British colonial authorities soon proscribed the book for its blatantly propagandist content.

Roy sheds light on how the Aligarh Muslim University (AMU) turned into a prominent centre for the dissemination of Nazi propaganda in India with the establishment of the German Society there. This society promoted Indian Muslim separatism while expressing tremendous admiration for Nazi Germany and projecting it as a model to emulate in the State of Pakistan that the Muslim separatists aspired to establish. The propaganda literature produced by it went to the extent of comparing Hitler with Muhammad, the Islamic prophet.

Roy studies the different levels of ‘self-coordination’ of three Indian knowledge providers – Koodavuru Anantrama Bhatta (b. 1908), Tarachand Roy (1890-1952), and Devendra Nath Bannerjea (c. 1880s-1954) – and points out the rewards they earned for their services to the Nazis. She laments the total absence of records of indigenous responses to the Nazi propaganda emanating from the texts produced by them and Hermann Beythan (mentioned above), unleashed in India in several of its vernaculars through various channels. She realises that this lacuna makes it impossible to gauge how Indians responded to the Nazi propaganda and whether it left any impact on them.

Roy also finds it hard to assess the impact of the magazine Bhaiband (‘Brotherhood’), published in modern Indian languages for the Indian Legion, made up of 3,500 volunteers from the Indian prisoners of war (PoWs) who had fought Rommel in Africa. The aim of the magazine was their ideological indoctrination in the Nazi worldview as part of the training they were to receive from the German military for integration into the Wehrmacht (the German Armed Forces). Whether the magazine was successful in achieving its aim is hard to say because those Indian soldiers remained practically voiceless.

However, Roy is successful in achieving her objectives. She successfully describes the strategies the Nazis used to influence scholarship ideologically and politically, explains the nature of relations between established universities and the many external institutes established by the Nazis, and gives an overview of the role the scholars played in the formulation and implementation of policy in the service of the state and the National Socialist party. She also probes the fortunes of politically compromised scholars and investigates how a pattern of group exoneration emerged in West Germany as part of its efforts to come to terms with its Nazi past.

Roy’s book is a brilliant piece of scholarship, indispensable for any study of the connections between British India and Nazi Germany, specifically Nazi Germany’s efforts to influence Indian public opinion.

The Nazi Study of India & Indian Anti-Colonialism: Knowledge Providers and Propagandists in the ‘Third Reich’ (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2024) by Baijayanti Roy

Navras J. Aafreedi is an Assistant Professor of History at Presidency University, Kolkata.