I.M. Lall’s Legal Battle and the Travails of a Civil Service Officer in the Colonial Era

Chander M. Lall’s short biography of his grandfather is an account that wades through the life and travails of I.M. Lall, an officer of the Indian Civil Services (ICS) between 1922 and 1957.

The author traces the life of his grandfather through tumultuous events such as World War I, the Gandhian phase of the struggle for independence. It was during this period that Lall graduated to become a lawyer, entered the Civil Services as an officer in the judicial side and the family landed in Sheikhpura, then in undivided India.

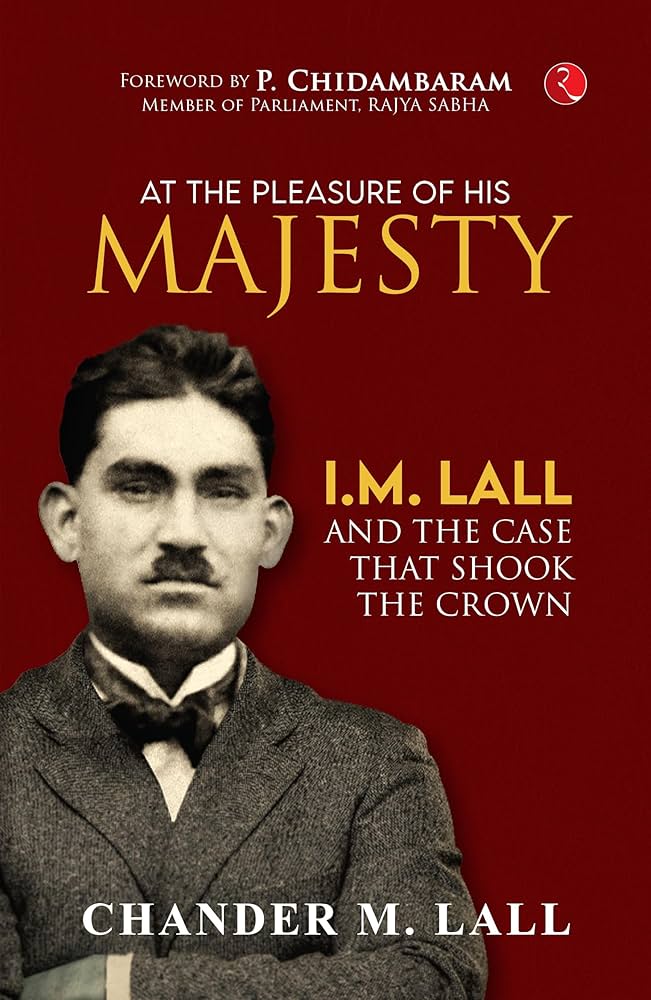

Chander M Lall,

At the Pleasure of His Majesty: I.M. Lall and the Case that Shook the Crown,

Rupa Publications, New Delhi (2024)

The brief and precise account of these years in Lall’s life is located with some felicity in the early chapters of the book. The author also gives an account of the administrative reforms in colonial India and how the ICS examinations, held only in London for long, had begun to be held in Indian towns as well.

The fifth chapter begins with Lall’s posting in the North-West Frontier Province in 1935, where his troubles with the regime subsequently began. Lall was served with a termination order in August 1940, after some cursory proceedings against him, without giving him an opportunity to defend himself. In other words, this was a case of dismissal from service with the right to natural justice denied to him. The following chapters of the short book describe the legal battle mounted by Lall, which was taken up to the Privy Council, culminating in justice and his reinstatement on March 18, 1948.

Chander's account, though interesting, seems to suggest that the case involving his grandfather and his legal battle led to the inclusion of Article 311 in the Constitution. This, in my view, does not stand up to scrutiny, especially of the record of events related to the history of Article 311.

The principle of natural justice, Audi Alteram Partem, that no person shall be condemned unheard, is indeed among the important aspects of modern society and the foundation of the rule of the law. Article 311 of the Constitution enshrines this. This article was added to the draft prepared by the Constitutional Advisor, Benegal Narsing Rau, by way of an insertion by the Drafting Committee.

A short history of the making of Article 311 will help comprehend the book under review and locate the importance of Chander's addition to scholarship on service law. The Constituent Assembly had mandated Rau to prepare a draft, drawing from his scholarship on constitutional laws from across the world. It had in it a provision pertaining to recruitment and conditions of service of government servants. This provision – Article 216(2) – read as:

"The recruitment and the condition of service of persons appointed to any such service shall be regulated by or under Act of the Federal Parliament and until provision in that behalf is so made shall be regulated by rules made by the President."

This, however, was found to be inadequate by the Drafting Committee, to whom Rau’s draft was conveyed by the Constituent Assembly for scrutiny. On February 3, 1948, the Drafting Committee decided to omit this provision in Rau’s draft and instead agreed to insert article 216-A. The new article, which would become article 282(2) of the draft Constitution, read as:

"No person who is a member of any civil service or holds any civil post in connection with the affairs of the Government of India or the Government of a State shall be dismissed, removed or reduced in rank until he has been given a reasonable opportunity of showing cause against the action proposed to be taken in regard to him."

In other words, the principle of natural justice, hitherto not found in the laws governing conditions of employment in colonial India was now brought in and accorded the status of a constitutional right in independent India. Article 282 would become article 311 of the Constitution on 26 November, 1949 and would serve as a bar against indiscriminate and malafide actions by the government against its employees. The Central Civil Services (Classification, Control and Appeal) Rules, 1965, indeed a protective armour in the hands of government employees, and used to the hilt by lawyers engaged in service law, was the outcome of this article in the Constitution.

Chander, a lawyer in his own rights, recalls a significant moment in his grandfather’s life: from August 10 1940, when he was dismissed from the Indian Civil Services, the long years of his legal battle, to his victory on March 18, 1948 in the highest court of the land at the time. The Privy Council declared the dismissal void and Lall was reinstated. The case was premised on the fact that Lall’s dismissal was ordered without giving him a chance to defend himself, making it void.

The Drafting Committee had decided to put Article 216-A to the draft a few weeks before the Privy Council had decided the case. Chander could have brought out this fact into his work and that would have added immense value apart from the context of the case. The point is jurisprudence, as is the case with any other knowledge and system, is the outcome of its own time. The Common Law principles, which indeed, had their substantial influence on several aspects of the law in the colonies in their post-colonial project are necessarily important aspects to study.

Chander's subject matter, here, is not about jurisprudence; his concerns are to account the story and the life of his grandfather and the book does justice in that sense. The travails of an ICS officer in the colonial era, Partition that put the family through a lot of difficulties and the fact that Lall was a man who refused to submit, taking the fight to London, even when it involved a drain on his finances. And it is important, for lawyers engaged in the branch of service law, to know the substantive case law that is cited most often in the courts – High Commissioner of India and Others vs I.M. Lall – is the outcome of one man’s fight, against all odds, to justice.

Krishna Ananth is an observer of politics and is the author of India Since Independence: Making Sense of Politics.

This article went live on July thirtieth, two thousand twenty four, at zero minutes past three in the afternoon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.