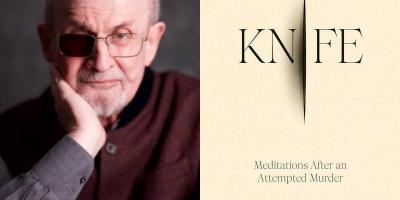

New Delhi: While the worldwide support he received after being attacked in August 2022 buoyed him, Salman Rushdie has written in his memoir on the attack about India’s silence. “India, the country of my birth and my deepest inspiration, on that day found no words,” he writes in Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder, released globally on April 16.

According to The Guardian, Rushdie details how he woke up in the hospital and opened one eye (the attack left him blind in one eye). While there, he learnt of a “worldwide avalanche of horror, support and admiration” in the aftermath of his stabbing. Even leaders who had criticised Rushdie in the past – like former UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson, who had said Rushdie didn’t deserve his knighthood – had stood by him and condemned the horrific attack. But the Narendra Modi-led government in India said nothing – and only a few political leaders, like Communist Party of India (Marxist)’s Sitaram Yechury and Congress’s Shashi Tharoor – spoke out on the matter.

In Knife, Rushdie talks about both the attack – how he felt unable to move or fight back, how he felt he was about to die – and its aftermath, including PTSD nightmares. Despite not believing in miracles, he says he saw his recovery as miraculous. “The reality of my books – oh, call it magical realism if you must – is now the actual reality in which I’m living,” Rushdie writes. “Maybe my books had been building that bridge for decades, and now the miraculous could cross it. The magic had become realism. Maybe my books saved my life.”

In August 2022, Rushdie was stabbed repeatedly in the neck and abdomen on stage at the Chautauqua Institution in New York State where he was to give a lecture. The attacker, Hadi Matar, has pleaded ‘not guilty’ to charges of assault and attempted murder.

The attack left Rushdie blind in one eye and he lost sense in some of his fingertips.

Before this stabbing, Rushdie was subjected to death threats due to alleged blasphemy in his fourth novel The Satanic Verses. After the supreme leader of Iran Ruhollah Khomeini issued a fatwa calling for Rushdie’s death in 1989, Rushdie spent years in hiding, living in isolation with round-the-clock security.

One of Rushdie’s most celebrated books is Midnight’s Children, magical realism set at the moment of India’s independence in 1947. The India he was using as the backdrop of his novel was for him a place of hope. But 40 years after it was published, in April 2021, Rushdie wrote in The Guardian that India is “no longer the country of this novel”. He documented the rise of authoritarianism and Hindu nationalist extremism, and said they “encourage a kind of despair”:

“Forty years is a long time. I have to say that India is no longer the country of this novel. When I wrote Midnight’s Children I had in mind an arc of history moving from the hope – the bloodied hope, but still the hope – of independence to the betrayal of that hope in the so-called Emergency, followed by the birth of a new hope. India today, to someone of my mind, has entered an even darker phase than the Emergency years. The horrifying escalation of assaults on women, the increasingly authoritarian character of the state, the unjustifiable arrests of people who dare to stand against that authoritarianism, the religious fanaticism, the rewriting of history to fit the narrative of those who want to transform India into a Hindu-nationalist, majoritarian state, and the popularity of the regime in spite of it all, or, worse, perhaps because of it all – these things encourage a kind of despair.

When I wrote this book I could associate big-nosed Saleem with the elephant-trunked god Ganesh, the patron deity of literature, among other things, and that felt perfectly easy and natural even though Saleem was not a Hindu. All of India belonged to all of us, or so I deeply believed. And still believe, even though the rise of a brutal sectarianism believes otherwise. But I find hope in the determination of India’s women and college students to resist that sectarianism, to reclaim the old, secular India and dismiss the darkness. I wish them well. But right now, in India, it’s midnight again.”

Advertisement