Interview | Anuradha Roy’s Intimate Yet Expansive View of a Life in the Hills

More than 25 years ago, author-artist-ceramicist Anuradha Roy and her husband came across a derelict cottage at the edge of a Ranikhet estate and decided that was where they wanted to live. It was a year of changes – not only did they pack their bags and leave Delhi to build a life in the mountains, the two also started their own publishing house, Permanent Black, at the same time.

Writing about it now, in her first book-length non-fiction work Called by the Hills, Roy remembers how they decided to move in right after the basic reconstruction of the cottage was done, while it was still a “shell”. “The details, including the matter of dissuading snakes and scorpions in their quest for rent-free accommodation, could be dealt with over time, we thought, partly because we had run out of money. We did not know that ‘over time’ would mean the rest of our lives, and that the transformation would eventually have more to do with us than the cottage.”

Anuradha Roy

Called by the Hills

Hachette, 2025

Perhaps that is why, when the publisher of Roy’s fiction asked her to write a book about flowers in the Himalaya during the COVID-19 lockdown, she found that she couldn’t separate the flowers from everything around them, from the transformations she had felt and witnessed. Her initial response to the idea, she told me in a video interview from her pottery studio in Ranikhet, was one of resistance – “I didn't think I had any botanical knowledge.” She is a keen gardener, though, and large parts of the book centre around the patch of land outside the cottage which she dreamt of turning into a “cultivated and beautiful wilderness” where she plants flowers, feeds birds and watches her dogs play. When I called it a “garden” though, she laughed – “Actually, it's not much of a garden, it's really just a pretty scrubby patch of hillside, even now. And I have three dogs and a fourth who is a puppy and they make sure there's no garden left.”

“When I began writing it [Called by the Hills], I did start with writing about the flowers. But I soon saw that I couldn't separate the flowers from the place they grew and the people who were around who knew about them or who helped me to grow them or from whom I stole cuttings and so on. And so, bit by bit, it became a kind of story of the place and the people where these flowers were.”

The author of five celebrated works of fiction, including Sleeping on Jupiter and The Atlas of Impossible Longing, Roy talks of her fiction writing process as “exhilarating”, describing the way characters come to live in her head, speak to her and go for walks with her much before anyone else ever gets to meet them. Writing fiction, she told me, leaves her feeling “hollowed out” at the end – “as if somebody has taken an ice cream scoop and taken everything out of me”. This book was different – the people and places she mentions were all around her, before, during and after the writing process. “It was a very joyful and relaxing process for me to just sit down and look around me and write about things I could see and hear, and people I could actually meet, rather than just in my head.”

Despite living in the mountains, Roy is not a hiker or a camper. Describing how she chooses to engage with the world around her in Ranikhet, she writes in Called by the Hills, “My version of exploring the mountains is perhaps a more intimate one, which doesn’t have the drama of extreme terrain but consists in getting to know my immediate environment as closely as if I were a lover who needed to understand and memorise every detail of the beloved: the folds of the hills, the bushes in its dark and secret parts, the contours and curves, the changes of light and the changes of colour in each season.”

Anuradha Roy. Photo: Sharmi Roy

“I grew up as a child of a geologist and he used to be away from home for six months of the year right through our childhood, because he used to go on these very long field surveys,” Roy told me, explaining both her love for exploration and why camping in the mountains is not her idea of a good time. “And on many of these, he was allowed to take his family with him, but they had to live as he did because these were extremely remote areas and we lived in tents. I think that probably my attraction to wild spaces even now comes maybe from that – I was two months old when I first lived in a tent and that continued till I was about five or six years old. But what that did was to really drive all attraction to tents out of me for good. I have never ever wanted to go on a trek and lie in a tent. I'm sure it's wonderful, but that's not what I wanted.” Instead, she wants to know the forests, trees and other forms of life around her deeply, taking her questions to the people she meets and the books she reads. “And you keep discovering new things even when you've lived here for 20-odd years.”

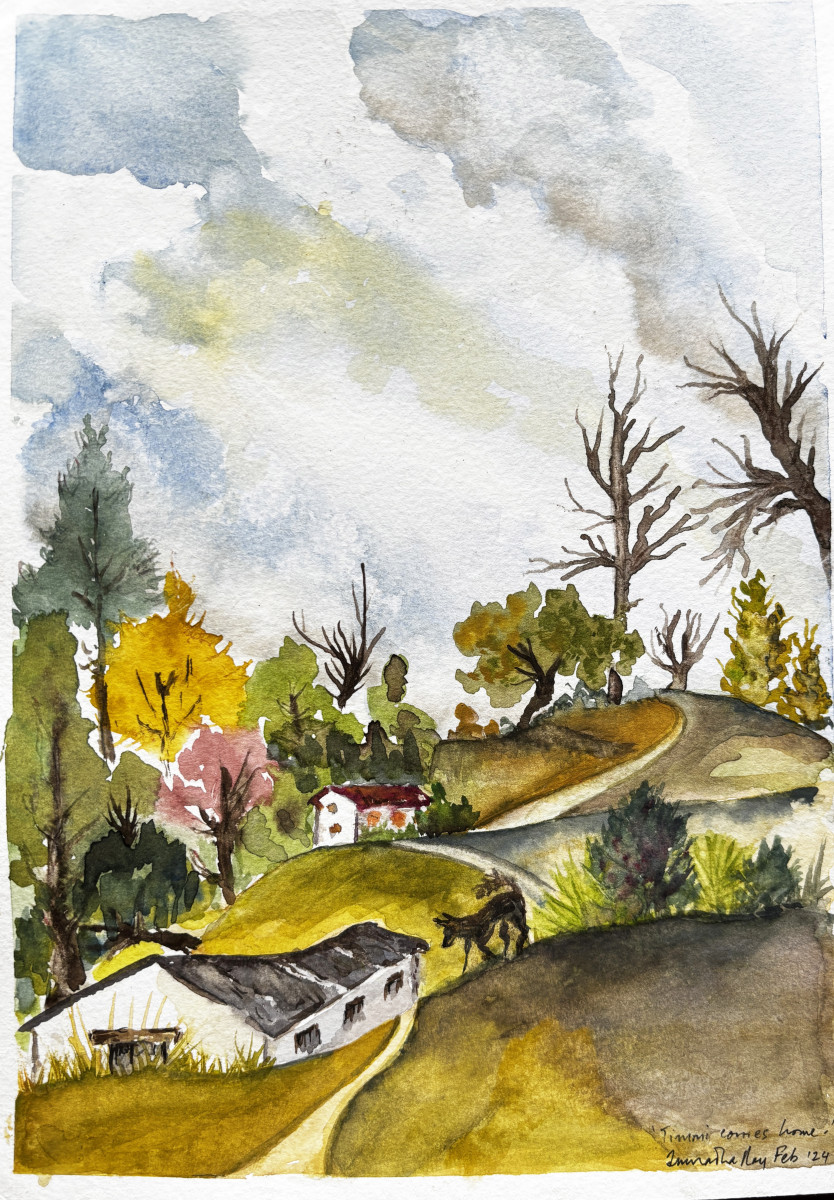

That discovery of the world around her is of course visible through Roy’s words, but in parts is made even more real for the reader through her watercolour paintings, spread across the book to highlight the plants, flowers and landscapes the words depict. The book wasn’t supposed to be an illustrated book, she says – but much of her diary notes over the years she has lived in the mountains took the shape of drawings, and so it was decided that the book should include that art.

“When I first came here, we had these very basic cupboards made by a village carpenter, and they were fairly wonky and not great to look at. …So I then began painting these cupboards. I found scenes from the forest, the leopards we saw and heard about, and the arum lilies that were growing in the garden.” The scenes-from-life drawings from the cupboard continued onto her diary, “and in the early days when making the garden, I tried really to keep an eye out for what grew when and to make a note of those so I would remember. That's how these paintings began.”

For a while, though, Roy says she had stopped painting entirely and “lost all link with colour and paint”. That link was brought back through her interactions with artist and poet Sophie Herxheimer, whom she met at a writing residency in Como, Italy.

Timmi Comes Home, by Anuradha Roy, from 'Called by the Hills'.

Xerxheimer is just one of the many people whose impact is visible in the book – on Roy’s writing and on the life she has built. Called by the Hills cites a range of books, on the mountains, on gardening and on writing, including some by people Roy spent time with after moving to Ranikhet.

Durga Kala, who spent years writing a biography of Jim Corbett, Roy told me, played a special role in bringing people together. “Mr Kala was like really a magnet who drew all this Himalayan scholarship into this little corner of Ranikhet. And we, by mere physical proximity and being in the publishing world, got to spend time with them, read them, had them tell us about other things we could read. And I became more and more interested in reading books, both about the Himalayas and other mountains and natural places. So I read Frank Smythe's Valley of Flowers, that's just a wonderful thing to read even now. And then Claire Leighton had beautiful etchings made by her [in the] story of how they made their garden – it became almost like a model for me. As was Jim Corbett's My India, and I read Verrier Elwynn's Leaves from the Jungle.”

While interactions with authors and their work had a profound impact on Roy, so did the words of those she met around her every day. Some of this impact is visible in the way Roy writes about making certain decisions: Should she plant non-native saplings in her garden because they were gifts from dear friends, or would that hurt the local ecology? Should she feed the birds who visit her garden, or will that make them dependent on a human carer?

I asked Roy whether the way she thinks about these questions has changed during her time in the hills. “I think that when I came to the hills, both as a visitor and then as somebody who began to live here, my ignorance was profound. …So it did need me to really unlearn quite a lot that I thought I knew and to pay attention to things and people I saw around me. And often, of course, you feel some sort of frustration and irritation when you are repeatedly shown up to be an idiot, but you often realise that there's good reason because you really don't know those things,” she said.

“And about the birds, yes, there have been wildlife biologists who've told me that having bird feeders in a wilderness of this kind is not okay and that they need to find their own food. And I completely understand and agree with that probably, but what can you do when there's a whole flock of them every morning screeching their heads off, saying, ‘You're eating breakfast, where is ours?’ So I'm afraid I sort of give in and that has happened with the birds,” she laughed.

Barbets, by Anuradha Roy, from 'Called by the Hills'.

Called by the Hills speaks of the beauty and allure of a life in the mountains – of the slow pace of life, of the intimacy with the natural world, of the joys of learning and unlearning. But it is also a realistic portrayal of the growing dangers and precarity faced by those living in the Himalayan region: calamities life floods have been both more frequent and more intense; leopards have made their way into human settlements, leading to both human and animal loss of life; construction and mining continues even as we see the ecological destruction they caused. Roy describes these changes and the sense of helplessness they have brought on for the local population – and how they impacted lives including her own.

“Where the rulers are oblivious to the needs of the citizens,” she writes, “wildlife and landscapes exist only to be commercially exploited. An invisible web of plutocrats and corporations controls the ruling regime as well as its rivals. There is resignation, cynicism and fury as government after government ravages the country’s forests and waters in a tight embrace with giant companies. Nobody can reverse this or stop it: it has been and will be coitus uninterruptus continuus until there is nothing left to destroy.”

She also believes that these disasters are not getting attention they deserve, she said in the interview. “These things [increased leopard attacks] are a huge cause for alarm, as is the way climate change is affecting all the glaciers, so that there are incredible disasters with the huge human tolls at high altitudes, which are not really talked about all that much as they should be. Had they happened in a place like Delhi, if 220-odd people were killed in one flash flood there, imagine how much people would talk about it. But when it happens up in the mountains, it comes out in the news for a day or two and then it's forgotten, but the consequences apply to everybody.”

When I asked about the state of resignation she writes about, Roy said, “It makes me feel very unhappy to see that, you know, when there should be anger and rebellion, there is usually resignation and attribution to destiny for all these things.”

This is not because they think these calamities are not man-made – but everything and everyone responsible feels out of their reach. “While you will find that people in the villages and small towns often blame destiny for their misfortunes, such as losing relatives in a flash flood or an avalanche or a landslide, I think it's a combination of being in the grips of things that are too big for you on the divine level, as well as the human level, and they are being crushed between these two things.”

This article went live on November twenty-fourth, two thousand twenty five, at nine minutes past seven in the evening.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.