Kahe Latif: A Milestone in the Imagination of Translations Within Indian Languages

A Sufi is not a show-off, screaming piety;

his world, his work is within him.

It’s a way of life none can fathom,

for a Sufi endears his foes.

Thus is phrased a lucid definition of a Sufi in the Risalo of the 18th-century Sindhi poet Shah Abdul Latif. Thanks to Rita Kothari’s recently published translation of the Risalo as Kahe Latif, Latif’s and the Sindhi idiom of Sufism is now available in free verse style, everyday Hindi. Kothari has been working on Gujarati and Sindhi literatures and translations largely vis-à-vis English; with Kahe Latif, she takes an audacious step towards bringing two Indian languages – Sindhi and Hindi – closer to each other than previous attempts to bring Sindhi into the larger Indian linguistic space.

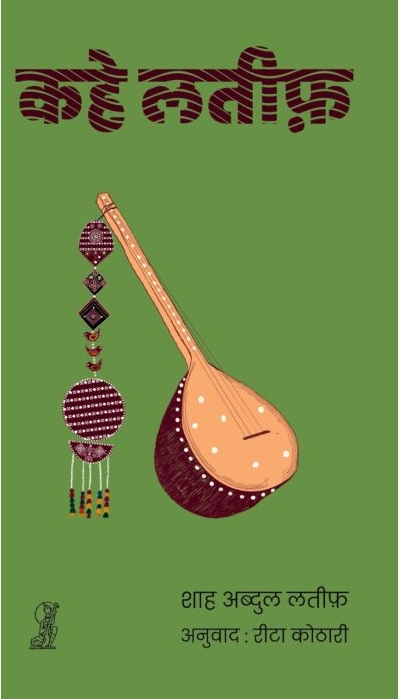

Shah Abdul Latif, translated by Rita Kothari

Kahe Latif

Vani Prakashan, 2025

Shah Abdul Latif (1689–1752) was born in a village near Hyderabad, Sindh, in a Sayyid family. He was erudite in the sense of being well-read or well-informed with the Holy Quran and Persian Poet Jalaluddin Rumi’s Masnawi by his side. His poetry was compiled by one of his disciples after his death as the Risalo, The Message. The text is divided into several books, with each book dedicated to a specific theme and to be rendered in a specific raga (known as ‘sur’ in Sindhi). The verses within the books sing praises to the Divine as the Beloved and in the voices of the heroines of seven folk romance-stories. Among these stories, the story of Suhini-Mahiwar is a variation of the Punjabi qissa of Sohni-Mahiwal. To those familiar with the Hir-inflected Punjabi voice of Sufi poetry, this might be a critical point of reference: that Sindhi and Punjabi shared the worldview of being in love and being devout.

Another point of similarity that will help the readers is Latif’s use of the metaphors of the Beloved and the intoxication that is associated with Sufism. Here is the gentle moon invoked in Kothari’s Hindi:

Sau sau suraj niklein yaa chauraasi chandrama

Yaa Allah! Priya bina sab jagah andhera…

Chaand, main na karta tumhaari barabari priya se

Tum roshan sirf raat ko, saajan nit savera

In English, that would roughly be:

Even hundreds of the Sun and the Moon

keep this world a dark pit without the Beloved…

The Moon shines only in the darkness,

the Beloved is always the dawn.

About wine, Kothari’s Latif says:

Ishq ki sharaab ka ek ghoont bada mehenga

Uski tamanna banaa de shahid, kintu

Kaam hamara ibaadat, nazar uss rehbar ki

In English:

One sip of this wine will cost you your life;

your yearning for Him will turn you into a martyr.

We can only offer our worship under His watchful eye.

One can go on playing with Kothari’s gentle Hindi, but what one must note here is the range of responses it will draw from the different kinds of readers.

Those who are familiar with the text will recite the Sindhi lines in the original while reading Kothari. And those who are not so familiar with the original will not be able to help trying to place her words into whatever little they know or remember of Sindhi. Sindhis who have heard of Latif but never read him because of the lack of access to the script or lack of familiarity with the literary and historical context of Latif’s poetry are likely to find the vocabulary of everyday wisdom in Kothari’s translation:

Vyaapaar karo unn cheezon ka jo hon na purani

Becho aisi cheezein jo munaafaa dein vilaayat mein

Dukaan chalaao aise jo de tumhein mukti

In English, that would sound something like this:

Trade only that which does not perish.

Sell only that which brings you a profit in the other worlds.

Run this business in ways that bring you salvation.

Another detail that is likely to dazzle Sindhis is the presence of the verse about the speaker urging the Divine not to aim an arrow at him: for since the Divine rests within him too, the arrow might end up hurting Him. The verse is a well-known one; it constitutes the opening lines of the 1968 Sindhi film Sindhu A Je Kinare. There might be countless more such instances of Latif scattered in Sindhi popular culture. Those who have the memory and the will to remember will find the Latif they know in Kothari.

In other places, Latif will be a surprise. For instance, he brings in new comparisons of secrecy as love. In Hindi, Kothari writes:

Rehne do apni ruhaniyaat parde ke peechhe

Na sunao dillagi ki kahani

Jo jaan lenge log, kahe latif

Toh roday aayenge raah mein

Roughly translatable as:

Let your intimacy remain behind the veil;

do not recount how love feels in your core.

If they hear any of it, says Latif,

there will only be trouble ahead.

Elsewhere, Latif talks about being in love as being thieves; lovers are those who plan their heists carefully. They keep their love only to themselves.

Rita Kothari.

As mentioned earlier, Latif’s poetry participates in the universe of stories known about Sufis and Sufism. For instance, one of the stories narrated about both the Punjabi Sufi poet Bulleh Shah and Latif is the same: they refused to learn anything beyond the first alphabet alif because there is nothing else to learn beyond the alphabet that begins the word Allah, and Allah is the Universe. The alphabet stands for the sum total of knowledge, like Kabir’s formulation of the two and a half alphabets of prem or love. Latif also invoked the yogis and their ways in his poetry. In one verse, he says one finds Hari, one of the names and avatars of Lord Vishnu in the Hindu pantheon, when roaming in the desert. If one were to find an intersection of Sufi-Bhakti traditions in South Asia, Latif would perhaps be the most poetic and evocative site to locate it. His ways of blending Islamic and Hindu ethos of divinity are what Kothari has called elsewhere in her scholarship as “being-in-translation”. The Sindhi way of life exists in translation from diverse faiths, but ironically it is the least understood or visible practice of translation.

One example of this invisibility ought to be mentioned here. Translation in India, at least the kind that is most visible, is skewed towards translation from Indian languages into English. If there are conversations happening within Indian languages, between authors and texts, they tend to be isolated from the mainstream understanding of translation practices. A cursory look at the history of translation in India outside of English would reveal that the first half of the 20th century witnessed a lot of activity; authors and translators seemed to have been participating in the nationalist fervour by showing solidarity with other languages and approaching their works with a sense of curiosity. Post-independence, Sahitya Akademi encouraged translations among Indian languages as a mandate by commissioning translations. Both before and after independence, Sindhi figures as one of the least translated languages and literatures. While plenty of translations from Hindi and Bengali were undertaken in Sindhi, other languages do not seem to have returned the affection. Similarly, while Sindhis translated a lot of works from other Indian languages into Sindhi, translations from Sindhi into other Indian languages are only a handful.

Against this background of an uneven exchange, Kothari’s translation of the work of the most revered Sindhi poet Shah Abdul Latif into Hindi as Kahe Latif should be seen as a much-needed signpost for Indian translators in their journey towards a sustained, invigorated and equitable handling of translation as power. Kahe Latif deserves to be seen as something more than a text. It is a statement on the silences around certain languages in the subcontinent – and is a challenge to translators, Sindhi ones specifically but also in general, to have the courage to bypass English as a norm for canon making.

Soni Wadhwa teaches Literature Studies at SRM University, Andhra Pradesh. Her digital archiving work includes PG Sindhi Library, Sindhi Halchal Archive, and Sindhi Sanchaya.

This article went live on November twenty-fourth, two thousand twenty five, at thirty-two minutes past eight in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.