A Memoir: My Grandmother's Flight From Karachi to Bombay in 1947

An excerpt from 'Inheriting the Hamam Dasta and its Stories,' a chapter by Maya Mirchandani in Looking Back: the 1947 Partition, 70 Years On, edited by Rakhshanda Jalil, Tarun K. Saint and Debjani Sengupta and published by Orient Blackswan.

Courtesy: Maya Mirchandani

The Wire’s #PartitionAt70 series brings a number of stories, through text and multimedia content that will attempt to draw a comprehensive picture of those weeks and months when entire geographies and histories changed forever.

Sometimes, on Sundays especially, I like to cook. I pull out my old notebook of family recipes and take down a beaten brass mortar and pestle to pound the spices I need. Over the years and several conversations, I have written down recipes for signature Sindhi cuisine, with my grandmother’s spectacularly revealing notes about how she conned us into eating stuff we didn’t necessarily like as children – Sindhi kadhi (no yoghurt, and lots of kokum and lots of vegetables), sai bhaji (put in all the vegetables no one likes to eat, they will never know) or sehal gosht (the easiest mutton curry recipe ever—just toss everything in together and let it cook).

In my home, I don’t think we have ever used the term mortar and pestle. We call it a hamam-dasta. And if it were a living thing, it would be the second oldest member of my family. Second only to my grandmother, Savitri, who arrived by ship to Bombay from Karachi in late October 1947 with two toddlers – my father who was two, and my aunt who turned one that month – one small suitcase of clothes and this hamam-dasta, packed for her without her knowledge by the lady who helped look after the children. So that even as a refugee fleeing the violence of Partition spreading to Sindh, she would be able to set up a kitchen no matter where she landed.

Dadima, as I call her, turned ninety-four in September 2016. She insists on living independently in her one-bedroom house in New York in spite of entreaties by her children to move in with them. On Tuesdays, she plays cards with a Sindhi friend she made there, about twenty years younger than her. Someone with whom she can speak in the language of her childhood, and what is still the language of her thoughts. If anyone drops in to see her, they will find her singularly engrossed in the rummy game. But her brood of children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren, who get their stubborn streak from her and insist on disrupting her game by walking through the front door unannounced, never tire of her stories.

Savitri Mirchandani (née Gidwani) was born in September 1922 in Hyderabad, Sindh, to a family of zamindars – the sixth of ten children. She moved to Karachi at the age of nineteen, as a young bride in December 1941. And there she lived with her husband, a police officer, his family and two very young children. Until one day, six years later, around the end of October of 1947, when she was rushed out of the house overnight. She cannot remember the exact date, but does say that my aunt had her first birthday in Bombay – on the 19th of November.

Sindh, especially upper Sindh, and also the cities of Hyderabad and Karachi had stayed calm for some time after the bloody Partition of August 1947. Sindhi Hindus – for whom language and culture came first, and religion second – had no intention of leaving their homes and lands. After all, unlike Punjab or Bengal, Sindh was not divided, but went wholly to Pakistan, and while they were concerned about their new status as a minority community in a new Pakistan, the question of leaving hung in the air without a clear answer. But as a new Pakistan went about the business of nation-building, on the streets and in mixed neighbourhoods, anger simmered. It was only a matter of time before violence flared. As mobs began to loot Hindu homes, and her husband Sunder, was on duty round the clock, helping to maintain law and order, her safety and that of her two young children became paramount.

After having retired as one of the few Indian officials working for the British-run Karachi Port Trust, her father-in-law, Rewachand Mirchandani had become a card-carrying member of Raja Ram Mohan Roy’s Brahmo Samaj, working for social reform in the city. To him, Savitri was a daughter and given the same status and liberties as Mohini and Rukmini, her sisters-in law. He was liberal but strict – qualities Dada also inherited. But that day, there was no discussion; only an order. After assessing the danger, he came home with a ticket for a berth on a ship that was sailing a few hours later to Bombay, where Savitri’s sister Sita lived.

I often tell Dadima that I consider all Sindhis Sufi. According to what I have learned from her over the years, in many families, the first son became a Sardar and many Amil Sindhis are Nanak Panthis, or followers of Guru Nanak, and follow many Sikh traditions, especially during weddings and funerals. My Dadima still recites from the Granth Sahib every day. My grandfather, on the other hand, pursued his father’s Brahmo Samaj ideals and while he was superstitious about the stars and planets (he famously threw my grandmother’s sapphire ring into the Indian Ocean when they lived in Colombo), he didn’t believe in any religious ritual. In that regard, perhaps we are unlike many families, but in my mixed-up home (my mother is Telugu), Dadima ensured that my brother and I learned our prayers from the Granth Sahib, and even today we recite them anywhere and everywhere we feel like or in places of worship, irrespective of faith – at Gurudwaras of course, but also at dargahs and churches or at the most traditional Hindu temples.

Dadima recounts from memory the terror she felt that night. Like most days and nights at the time, my grandfather was at work. The governor of Sindh had cancelled all leaves and rejected all resignations from police officers, irrespective of their religion. After a posting in Larkana, where he made local headlines for having killed a ‘dacoit’ in an encounter, my grandfather was finally back in Karachi. The city was burning and the governor needed his men. Hindu neighbourhoods and their women were suddenly no longer safe, and her frantic arguments against leaving home, her pleas to stay, to contact my grandfather, all fell on deaf ears. Rewachand told her not to worry, Sunder would be told, but she simply could not stay.

Today Dadima loves to tell everyone that she travelled from Karachi to Bombay in the same ship and in the same cabin that Fatima Jinnah had made the reverse journey in. No one understands why she so has clung to this story. Perhaps because it allows her a chance to make sense of her hurried departure from Karachi – after all, others who had made Bombay their home were doing the same, in reverse. Sindh was part of the Bombay Presidency and the two were considered sister cities – bustling, cosmopolitan and wealthy. Telling us about the ship and of strangers tied together by a shared experience must make it easier for her to talk about it. I don’t know about Ms. Jinnah – who left behind a thriving dental practice in Bombay – but I do know about Dadima. The thought of having left for good was somehow inconceivable to her. Maybe my grandmother’s domestic help who packed her hamam-dasta without telling her knew better.

It wasn’t until after some months later, during which there was absolutely no communication, when my grandfather was finally able to resign from his job and make the journey to India; Dadima says it was a little after Mahatma Gandhi was assassinated in January 1948. But there was an uncomfortable condition to his resignation, a final assignment. He had to escort a train-load of Hindus fleeing from Sindh – alive, wounded or dead – across the newly created border. His resignation letter was submitted and accepted only once the assignment was complete, at Khokrapar, on the border inside Rajasthan.

It wasn’t until after some months later, during which there was absolutely no communication, when my grandfather was finally able to resign from his job and make the journey to India; Dadima says it was a little after Mahatma Gandhi was assassinated in January 1948. But there was an uncomfortable condition to his resignation, a final assignment. He had to escort a train-load of Hindus fleeing from Sindh – alive, wounded or dead – across the newly created border. His resignation letter was submitted and accepted only once the assignment was complete, at Khokrapar, on the border inside Rajasthan.

Dada – Sunderdas Rewachand Mirchandani – a lawyer by training and a policeman by profession, was a man of letters. Fluent in Farsi, nothing was more valuable to him than his books. He had some time to prepare before he left for Bombay and so he carried a few things he felt were important – a book of historical essays he had received as a prize in college, a wedding photograph and the front page of The Sind Observer with the lead story of Germany’s unconditional surrender in World War II. And for Dadima, he brought some jwellery and her wedding sari. A royal purple organza with bunches of grapes all over, woven in pure silver zari. So delicate that it is now frayed and split into pieces, one of which I still wear on rare occasions as a dupatta, to much admiration.

Many Sindhis who arrived in similar ways to Bombay stayed on. The sea air, proximity to Karachi and the ability to speak in their own language with others from the community who arrived under the same circumstances made them feel close to the home they had left behind. In fact, Mumbai today has one of the largest Sindhi communities in the country and many of them have contributed significantly to the city’s cultural and financial character. Their entrepreneurial spirit is legendary – often admired and reviled in the same breath. In fact, my grandfather’s sister Mohini and her husband Gopal Sipahimalani (Sippy, for short) a practising lawyer in Karachi, who reinvented himself in Bombay as one of the most prominent film producers of his time, tried very hard to convince my grandfather to join them. But my Amil grandfather, who had no head for business and perhaps no stomach for painful nostalgia that gripped so many members of his family at that time, wanted to leave the lament of exile he heard all round.

For those who are unfamiliar with the class-based segregations in Sindhi Hindu society, the Amils (from the word Ámal in Farsi, meaning to administer) were well educated and mainly worked as accountants and lawyers. Some even held government positions – of the very few government positions that Indians were allowed during the Raj. Many Bhaibands – the other major Sindhi community of traders and businessmen – stayed back to protect their businesses as long as they could. But with relatively little in terms of trade and business interests to hold them back during the violence, most of the Amils fled, like so many others, across the Sindh province to India.

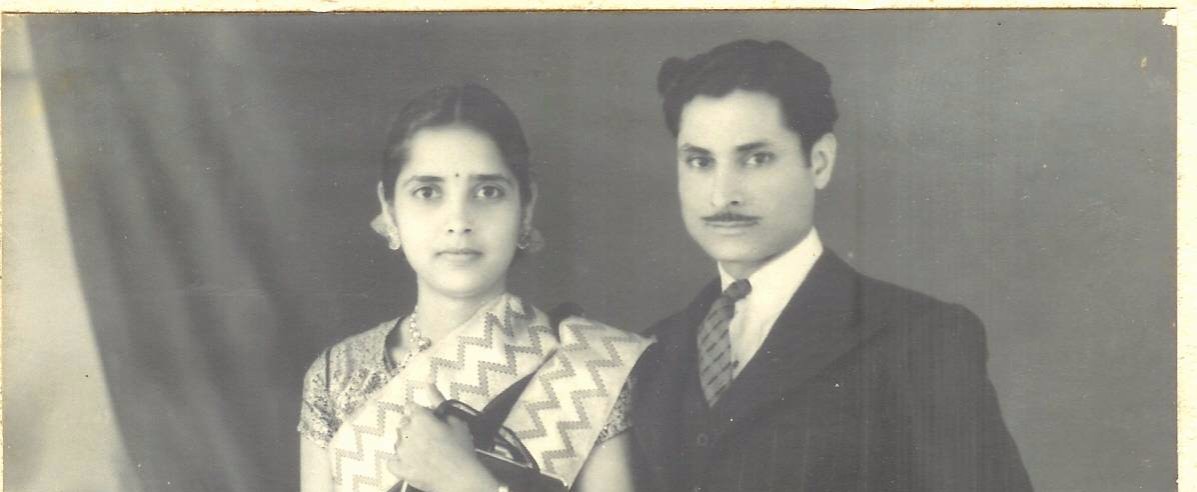

Savitri and Sunderdas Mirchandani (Dadima and Dada) on their wedding day, December 20, 1941. Courtesy: Maya Mirchandani

Days after he found Dadima in Bombay (not wanting to be a burden on anyone she had moved out of her sister’s place by then), the reunited family left bag and baggage for Delhi and lived as refugees, crammed into a single room with another of my grandmother’s sisters, Kalavati (Kala) and her family comprising a husband, Rochi and two children. In the Shershah Mess refugee camp, where the Delhi High Court now stands, Rochi uncle and my grandfather searched for work, joining the line every day to meet the government recruiters who came there. Ours is a family of civil servants and so, Sunderdas Rewachand Mirchandani decided he was going to do what he knew best – serve the new India in whatever capacity he could. Several weeks and many queues later, he was re-employed as a police officer, this time with the Gujarat cadre. Together, my grandparents and their three children (my father’s youngest brother was born twelve years after Partition) travelled all over Gujarat, and then overseas, as my grandfather went up the ranks of the Indian Police Service.

In the winter of 2004, fifty-four years after she was forced to flee her home and her culture and thirty years after my grandfather died, I decided to make the journey back to Sindh with Dadima. I had heard several stories of Partition survivors breaking down and bending to kiss the earth upon arrival in their villages in modern- day Pakistan, so as a caveat, I must state that my grandmother is not a sentimental woman. In my lifetime, even though the stories are told and retold, sometimes with embellishment depending on the audience, I have never seen her express either extreme joy or extreme sadness. And so, armed with a walking stick, she wandered about Karachi as a curious tourist more than anything else. We drove around the city’s formerly Hindu areas in circles – what were empty maidans once were now built-up colonies, old bungalows had given way to swanky new buildings, all but obscuring the streets and landmarks of the Karachi that she once knew.

But Hyderabad, the small dusty town of her birth two short hours north of Karachi, was different. The city had grown, but its core felt familiar to her. In the small narrow streets of Hirabad, the formerly Hindu neighbourhood where my grandmother spent so many of her early years, the old havelis still stood (at least twelve years ago, they did). Engraved in stone at the entrance were names of the families who had once lived there and the dates they were constructed – testaments to the affluence of the original inhabitants. It is hard to say what happened to the individual residents of each home, but in all likelihood their stories must be similar to that of my grandmother’s. The journeys and histories of so many like my grandmother’s family who left Sindh and suddenly found themselves landless, homeless and most importantly, stateless, is largely undocumented. While many of the Hindu families from upper Sindh moved south into the cities after these homes were vacated, the vacuum created by the sizeable community’s departure was largely filled by Muslim refugees from India – the muhajirs, as they are called in Pakistan today. While the Muslims from Punjab settled mostly in and around Lahore, those who left Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Bengal, Madhya Pradesh, settled in Sindh.

So it was a more than special surprise when, while searching for my grandmother’s childhood home in Hyderabad, we were directed to an original resident in one of these havelis. For two complete strangers – my eighty-two-year old grandmother and eighty-eight-year old Dadi Leela at the time – their connection was almost immediate. In 2004, when they met, Leelawati Harchandani, better known to everyone as Dadi Leela (Dadi means older sister in Sindhi), was the oldest living Amil Sindhi in Hyderabad. Her memory was sharp, and her wit still dry. She told us the entire neighbourhood emptied out at the time of Partition, including members of her own family, but she couldn’t bring herself to leave. When I asked her why, she replied: "When I was a little girl, my headmaster told me I had three mothers. I remember getting very offended, as though he was saying things against my father. Then he explained to me who the three were. He said the first was my mother who gave me birth. The second was my mother tongue. And the third, my motherland. I never forgot that."

My conversation with her was in Urdu; I understand Sindhi but unfortunately, cannot speak it. My grandmother and Dadi Leela, however, spoke in the language of their mothers, their childhood, and their hearts. And as I listened, half understanding their conversation – fast and furious with excitement and nostalgia – I couldn’t help but reflect on the idea of home and the nature of identity. I watched as Dadima, elegant and cosmopolitan – she who called Delhi and New York home – transformed into Savitri, the young girl from Hyderabad, Sindh.

Dadi Leela was a singer. My grandmother has always urged me to learn Sindhi kalams – odes to the Lord written by Sindhi saints like Shah Abdul Latif Bhitai and Shahbaz Qalander, whose shrines in Bhit Shah and Sehwan are visited every day by thousands of people. As my grandmother sat down with her on the charpoy in the sunny courtyard where she spent winter afternoons, Dadi Leela pulled out her harmonium for us, and together she and my grandmother sang these kalams of their youth, and mine – I have heard these songs sung at Sindhi gatherings in Delhi and Bombay all my life. And at the end of our visit, she told us she used to know my grandmother’s aunt, and directed us to the house she had lived in, almost next door. A family from Aligarh opened the door and their home to us and asked us to stay as long as we liked. Karachi, Pakistan’s bustling commercial hub, may have been completely unfamiliar, but this short afternoon in Hyderabad, my grandmother’s city made our entire trip worthwhile – as though we had found home.

Today, after over a decade since we went, the stories of that trip, rounded off with a visit to Panja Sahib Gurudwara in Hasan Abdal, have been added to Dadima’s kitty of tales that make up our family history. Her travels in Sindh, like her memories of 1947, are told and retold to family and friends. At home in New York, where her self-taught English has become her first language, the only one who can speak in Sindhi with Dadima is her Tuesday afternoon Rummy companion, and the occasional extended family member who visits.

It wasn’t always like this. When she first moved there in 1985, there were many like her – Sindhis of her generation who had lived all over the world and finally decided to create a home where their children had come to live and work. When they met, conversations were a happy, even if sentimental mix of nostalgia and entrepreneurship, of what home has come to mean for so many of them – where statelessness and exile were superimposed with discussions of new horizons and challenges. While Delhi and Mumbai particularly, followed by cities like Ajmer and Ahmedabad have sizeable Sindhi communities, the community has spread itself all over the world. From Japan to the Caribbean, from South America to Europe, and every place in between, Sindhis are running businesses, own real estate, and adopting new cultures and nations along the way. That is what happens when an entire ‘nation,’ in the ideological sense of the word, becomes stateless.

Dadima, like her few surviving friends, has learned to adapt to new cultures and identities, even within our family. While for some of them the adapting has been about new cities and cosmopolitanism, at home my Telugu mother has introduced the Mirchandani clan to a new cultural sensibility and cuisine; my brother is married to an American of Irish and Danish heritage. In that, I suppose we are not an oddity. Generation after generation, like with so many other cultures and communities, the ‘Sindhi- ness,’ as it were, is getting diluted. Today, even though she tells us not to disturb her concentration when we walk through the door, Dadima speaks our language and listens to our music.

I like to think, though, that the core of who we are as a culture, as a people, has not changed much. My grandmother’s resilience, her perseverance in the face of adversity are to me singularly the most impressive and abiding traits of an entire community. She has held on to them for dear life and passed them on to her children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren, despite our mixed identities and the many places we call home. We all still look forward to our Sunday lunch. In New York, her recipes – including her famous methi fish curry – have found their way into the menu of my brother’s Manhattan bistros. And in my kitchen in Delhi, I pound my spices fresh in that precious hamam-dasta, checking my recipe book as I cook lunch for my retinue of friends who walk through the door in much the same way as we walk into my grandmother’s house – demanding our favourite food. As the sai bhaji simmers in its pot, the scents of my kitchen remind me of Dadima and the flavour of home she carries with her, and that will stay with me wherever I am.

Maya Mirchandani is a senior journalist.

This article went live on August fourteenth, two thousand seventeen, at thirty minutes past eight in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.