While memoirs of political prisoners are not uncommon, what one doesn’t often find is their stories told through interviews which probe the more intimate aspects of their lives and the enduring ways in which their incarceration has affected their families and loved ones.

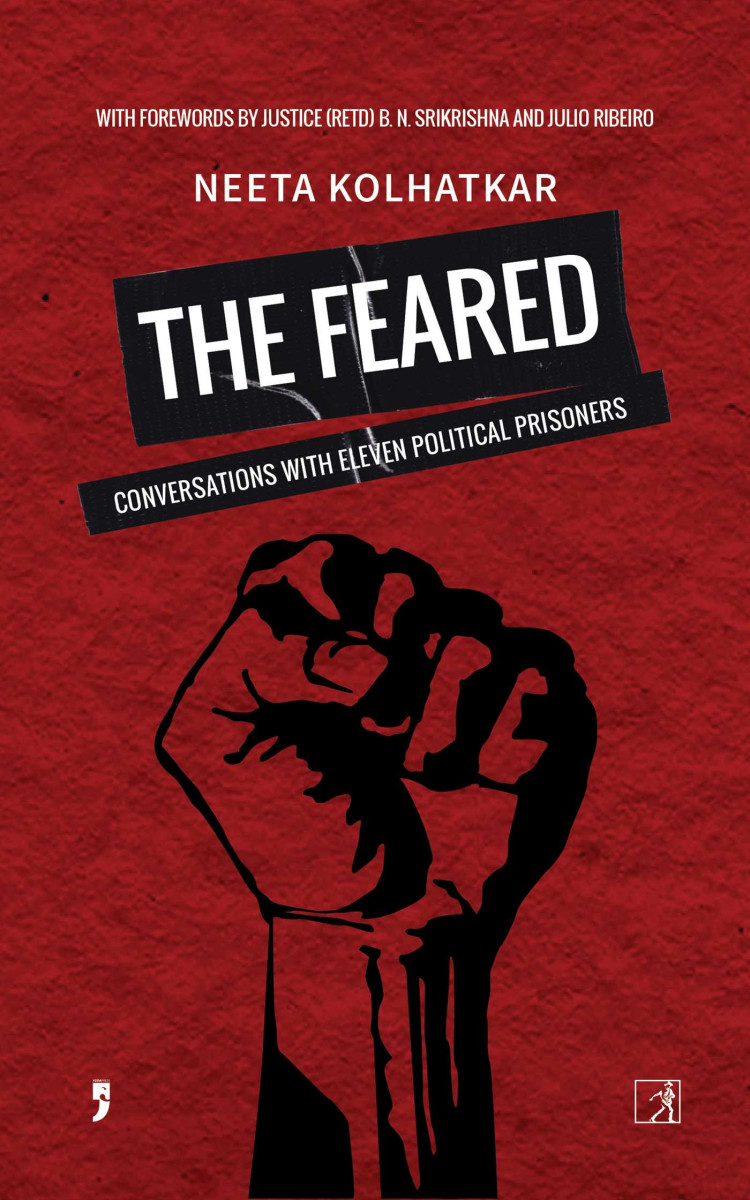

In The Feared, a book that is just as moving as it is unsettling, journalist Neeta Kolhatkar interviews 11 political prisoners (described in the book as those who speak up against the government of the day) and their family members. The interviewees range from the accused in the Elgar Parishad case to politicians from opposition parties, journalists and doctors. The book explores the events that lead to their incarceration, and the lives of the interviewees while they were in prison and after being released. While some of them have been released after being acquitted of the charges against them, many of them are out on bail with the looming threat of possible re-incarceration.

Neera Kolhatkar

The Feared: Conversations with 11 Political Prisoners

Simon & Schuster, 2024

The 11 interviewees recount their experiences serving lengthy periods in prison, their repeated arrests, unlawful detentions, the appalling conditions of Indian prisons, particularly those in Maharashtra, and the sheer indignity of being a Indian prisoner.

One learns of the struggles of not just the subjects but their family members, many of whom have dedicated years of their lives fighting for the release of their loved ones. The most striking aspect and one that runs through all 11 interviews is their concern for the anguish that has been caused to their family members due to their incarceration. Sudha Bhardawaj talks of the guilt of not being able to spend time with her daughter; Binayak Sen speaks of pressure that his case put on his wife and two daughters and how he regrets this tremendously; Sameer Khan breaks down while reflecting on the trauma caused to his wife and children due to his imprisonment.

Through this, we learn of the opaque “mulaqat” system or one-on-one meetings with family members and how this varies greatly from one state to another. Several of the interviewees talk of the severe restrictions put in place during these mulaqats in Maharashtra and of being able to see their family for merely 5 to 10 minutes every couple of weeks. We learn that “gala bhet mulaqat” (hugs) are only allowed to those prisoners who have children below the age of 16 a few times a year while other prisoners have to cope with the pain of (infrequently) seeing a loved one through a glass screen. The book tells us, for example, of the ordeals of those like Rama Ambedkar (Anand Teltumbde’s wife) who had to travel for six hours only to be able to see her husband for 10 minutes through a glass barrier. Their trials were exacerbated due to the Covid-19 pandemic. All mulaqats had stopped during this time. Nilofer Malik (the wife of Sameer Malik) talks about finally being able to see her husband after several months once the pandemic restrictions were lifted, but the torment of having to do so from five feet away across a glass partition was a shattering experience for her.

The book highlights the uniquely human ability to find joy and even purpose in the bleakest of circumstances. Kolhatkar is as eager to learn about her interviewees perspectives on politics as she is to know about their daily routines in prison and their coping mechanisms. She discovers how watching cats, doing crosswords and sudoku, and helping their fellow inmates navigate their court cases and aiding them in whatever way possible has kept many of the interviewees from despair.

Interestingly, while being probed about their struggles in prison, almost all of the interviewees draw attention to the fact that they are relatively better off as compared to other prisoners, the majority of whom are from marginalised communities. On account of the fact that many of their cases receive media attention, the prison officials often treat them differently, even with respect, we learn. They have access to good lawyers, they receive the support of civil society groups and sympathisers. They are also able to follow the developments of their respective cases.

Neera Kolhatkar.

This is not so with most other prisoners. Sudha Bhardawaj talks about how most of the women in Byculla have been abandoned by their families and receive no support of any kind. They are unable to follow what is happening in their cases and have no idea how long they are likely to remain in prison for. Although the lives of the interviewees have been challenging in unique ways on account of being “political prisoners”, we learn that the lives of those who do not have any such special, distinctive tag are far, far worse. Remarkably little is written about entire classes of prisoners whose identities themselves are criminalised or whose lives are not deemed valuable enough but have suffered immensely.

Although the book is meant to be a story of the struggles of those characterised as political prisoners, the book is ultimately a human story of resilience. While it is evident that their experiences have caused many of the interviewees physical and mental trauma, it is clear that their prolonged incarceration has not had the intended effect of breaking their spirit. If anything, their resolve has been fortified by many of their experiences in prison. For Bhardwaj, it made her realise the importance of legal aid to undertrial prisoners. She talks about her desire to file a PIL for legal aid to undertrials. Teltumbde speaks of how this was an important experience for him as a civil rights activist and the need of having prison rights figure on the agenda of democratic rights institutions, which is often not the case.

We learn that although many of the interviewees have been left in a state of limbo and anxiousness due to pending cases, their families too have suffered. Shikha Rahi (Prashant Rahi’s daughter) speaks of how has gone from the age of 24 to 40 fighting for her father’s freedom – how the whole world around her has moved ahead and she is stuck in time. Koel Sen (Shoma Sen’s daughter) talks about the bouts of anxiety and depression she has suffered. Even through all of this, far from any sense of resentment or anger, one senses only admiration and solidarity.

Fittingly, the book ends with a speech delivered by Hemlatha (Varavara Rao’s wife) at a conference in Delhi, titled ‘Companionship in a Journey of Courage’ and a poem written by Rao for Hemlatha expressing his gratitude to her for not just staying by his side but joining the struggle for a better world.

Through these interviews, Kolhatkar manages to reveal a more delicate, vulnerable side of the interviewees, compelling the reader to see them not as political prisoners but as humans.

Meenaz Kakalia is a lawyer based in Mumbai practising primarily in the field of environmental law and reproductive rights.