A Largely Unfair Assessment of Nehru Seen Through His Debates With the Other Leaders

In these highly polarised times in India, when the ruling dispensation is questioning and reordering almost every idea and institution that has defined the country since Independence, it is not surprising that Jawaharlal Nehru should be at the centre of ongoing debates – he was the colossus who shaped, with his personal vision, commitment and drive, India’s domestic values and its economic and foreign policies. Hence, as the tapestry of the old order is being carefully undone, Nehru must necessarily be the object of calumny and ridicule, as those with alternative visions and passions – and with the unblurred benefit of hindsight – tear into his persona and policy.

Tripurdaman Singh and Adeel Hussain

Nehru: The Debates That Defined India

Fourth Estate India (11 November 2021)

Two scholars – one born in India and the other in Pakistan, both nurtured in the narratives of their divided heritage in the cloisters of Cambridge University – have collaborated in producing this work that places Nehru in debate with four significant contemporaries: Muhammad Iqbal, Mohammed Ali Jinnah, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel and Syama Prasad Mookerjee. With all of them, he had fundamental differences of worldview, vision and strategy relating to India’s freedom and the policies that would define this nascent nation.

In respect of each personality, the authors have picked one specific theme that divided him from Nehru and set out in full the texts of their debate. Each debate is preceded by an introduction in which the authors provide the context of the discussion and a summary of the issues involved. Thus, a reading of the earlier documents gives a valuable background to our ongoing debates, while providing a fascinating glimpse of the personalities in contention and the rhetoric they mobilised to support their positions.

Communal solidarity and divide

Nehru met Mohammed Iqbal in Lahore in 1938, when the latter was quite incapacitated. Nehru approached him as a fellow socialist, but Iqbal’s principal concern at that point was the solidarity of the Indian Muslim community – he feared its integrity was being threatened by the Ahmadi movement, whose followers he saw as “religious adventurers”.

Nehru admitted that he lived “in the outer darkness” in matters of faith, but retained an abiding interest in the historical, cultural and philosophical aspects of religion. However, he noted with derision how opposition to legislative “restraint” on child marriage through the Sarda Act had brought orthodox Hindus and Muslims together.

After the engagement with Iqbal, which brought in matters relating to faith, culture, modernity and identity, Nehru’s exchanges with Jinnah are mundane, even sterile. This is because the letters included in the book are from 1938 – by this date, the two personalities were deeply divided in terms of their vision and agenda; and, while the formal demand for Pakistan was still two years away, the distance between the two was so deep that they could barely be civil to each other.

It is obvious that the divide between Nehru and Jinnah was rooted in fundamental differences in their worldview and vision for free India. Nehru fervently believed that the principal issue before the people was freedom, and viewed this as linked with “a broader global issue around imperialism”.

The real problems, Nehru believed, were economic and emerged from “exploitative capitalism”. Nehru asserted that the Hindu-Muslim problem “is not a genuine problem concerning the masses, but it was the creation of self-seekers, job-hunters, and timid people who believe in British rule in India till eternity”. None of this resonated with Jinnah who even said sarcastically that Nehru’s concerns about the “impending catastrophe that hangs over the world” reflect “thinking in terms entirely divorced from realities which face us [Muslims] in India”.

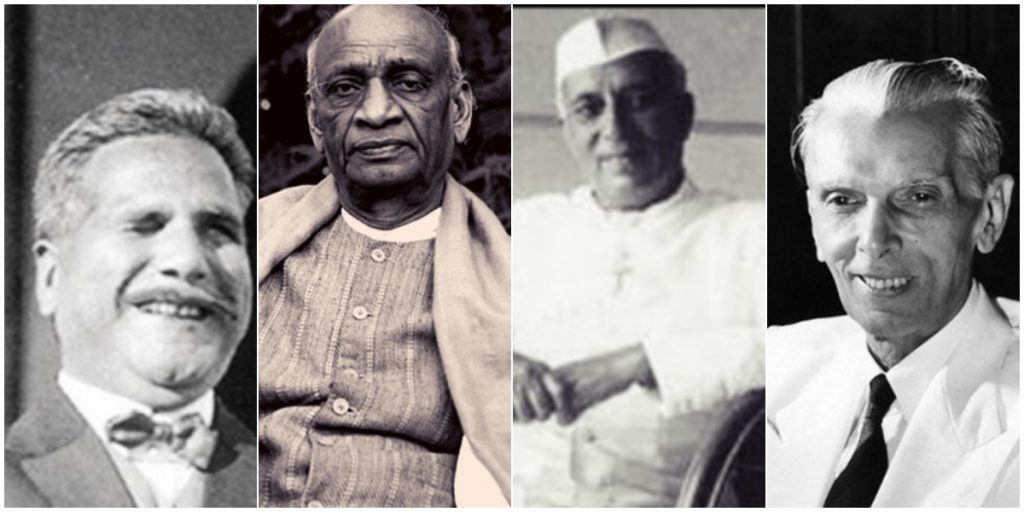

Iqbal, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, Jawaharlal Nehru and M.A. Jinnah. Illustration: The Wire

The constitution

The last two chapters in the book relate to the early days of independent India and discuss two issues – the constitution and foreign policy. Here, Nehru debates with two opponents: Syama Prasad Mookerjee, the head of the Hindu Mahasabha and Nehru’s ideological rival, and Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, his colleague in the Congress and deputy prime minister and home minister in the cabinet.

The debate with Mookerjee took place in parliament when, in May 1951, Nehru moved three amendments to the constitution that had been adopted just 15 months earlier. These amendments pertained to three articles in the ‘Fundamental Rights’ chapter – Articles 15, 19 and 31: these amendments, respectively, enabled the government to expand reservations to “backward classes”, imposed some fresh restrictions on the press, and freed the Union and state governments from judicial scrutiny in regard to laws relating to land reform.

Mookerjee in his lengthy remarks referred to the proposed amendments as “momentous and grave”, with “serious consequences” for the rights and liberties of individuals and the nation. What caused him concern was that the amendment to Article 19 included constraints of criticisms of friendly countries. In keeping with his party’s position on Akhand Bharat, he was deeply worried about media reporting on his party’s pursuit of the undoing of partition and the reunion of India and Pakistan.

Mookerjee castigated the government for “treating this constitution as a scrap of paper”. However, despite the sound and fury at the time, the amendments are barely recalled today, and certainly did not have the cataclysmic impact on personal freedoms that Mookerjee feared at the time. However, for the authors, the mild restrictions on free speech are “an outcome of the Nehruvian state’s determination to suppress political alternatives; a vital part of India’s Nehruvian legacy”.

Given India’s free and raucous media over the last several years, and the frequent swing between political alternatives over nearly five decades, surely this assertion has little basis in reality. In fact, it raises concerns about the authors’ own objectivity amidst the present-day contentions in Indian politics, much of which is centred on Nehru. This is affirmed by the authors’ astonishing observation:

“Boundaries between liberal and authoritarian visions of India, between Nehru and Mookerjee, … are not only more blurred than commonly imagined – they often do not exist at all.”

The authors would do well to contrast the ongoing assault on the media with the extraordinary freedom that it enjoyed over the previous seventy years.

The China question

The authors present the foreign policy debate with Patel largely in the context of relations with China. They contrast Nehru’s world view, anchored firmly in progressive anti-imperialism and “Asianism”, with Patel’s hardheaded and unsentimental critique of China, its intentions and the threat it poses to India. This is based on Patel’s well-known letter to Nehru, dated November 7, 1950, in which he refers to “China’s malevolence”, its perfidy, and that it is not a friend but a “potential enemy”.

Patel’s letter is in two parts: the first part raises concerns about the recent Chinese annexation of Tibet and the threat this poses to India. The second part sets out what India should do to safeguard its interests in terms of strengthening infrastructure in the border areas and developing policy positions on larger issues, such as the McMahon Line, representation in Tibet and China’s membership of the United Nations.

Nehru prepared a note for the cabinet on November 18, 1950 that addressed several of the points made by Patel and obtained cabinet approval a few days later. Patel passed away in December of the same year. The authors assert that, with Patel gone, “the challenge to Nehruvianism evaporated” and “Tibet was abandoned at the altar of friendship with China”. Losing all self-restraint, they refer to Nehru’s “vapid, ineffectual slogans of anti-imperialism and world peace”, but do not clarify what they mean.

The issue of Tibet was obviously much more complex than what the authors have set out here, nor was Nehru the naïve, uninformed idealist they have painted. As former foreign secretary Nirupama Rao points out in her recent book, The Fractured Himalayas, Nehru wrote to finance minister John Matthai in September 1949 – well before Patel’s letter – that “Chinese communists are likely to invade Tibet sometime or other … within a year”.

Nor did Nehru ever ignore Patel’s letter. Rao says that a day after receiving the letter, Nehru asked the secretary general in the Foreign Office to consider India’s foreign policy in the UN and in regard to neighbouring countries, including China, “with reference to our defence problems”. Nehru also took cognisance of Patel’s suggestions relating to infrastructure along the Sino-Indian border. A high-level committee was set up under the deputy defence minister to “study the problems created by the Chinese aggression in Tibet and make recommendations about the measures to be taken to improve administration, defence communications, etc, in all the frontier areas”.

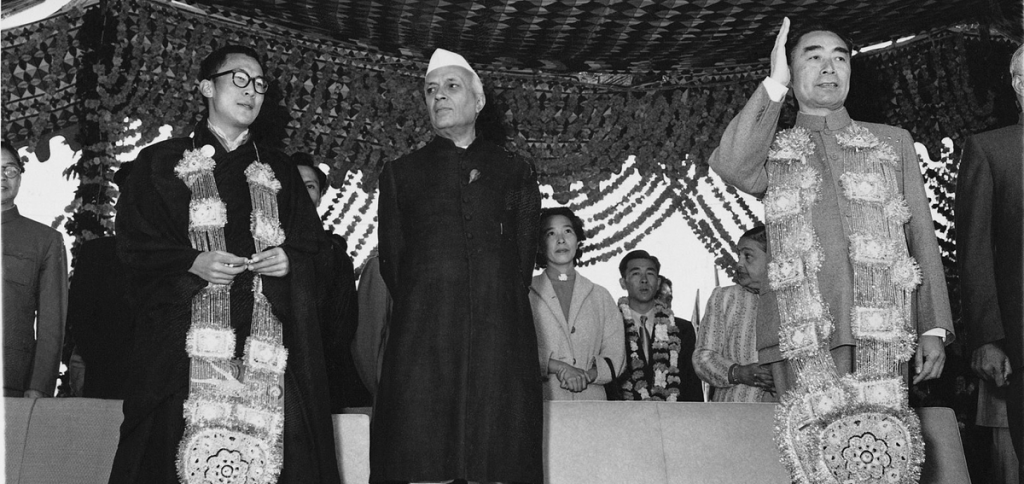

The Dalai Lama, Jawaharlal Nehru and Zhou Enlai in 1956 in India, at the UNESCO Buddhist Conference in Ashok Hotel, New Delhi. Photo: Homai Vyarawalla/Wikimedia Commons, Public domain

Instead, the authors highlight “the conceptual challenge to the Nehruvian worldview that was taking shape in the minds of Patel and many other detractors”. What they don’t say is that there was clearly an active US role promoting this position. Just three days after Patel’s letter to Nehru, on November 10, 1950, the US ambassador in Delhi, Loy Henderson cabled his secretary of state that the Tibet developments “had resulted in increasing dissatisfaction within the government with the direction of India’s foreign policy”.

Henderson then quoted Patel “stating privately” that he would shortly insist in the Cabinet “that India not only change policy in direction of closer cooperation with Western powers, particularly the US, but that it make an announcement to that effect”. The ambassador added that Patel planned to resign from the cabinet and “break openly with Nehru than to allow matters to drift”, and that he had the backing of several senior leaders in mounting what amounted to a coup d’etat to unseat Nehru.

The US obviously had a source fairly close to Patel and had been persuaded that the coup against Nehru would be successful. The ambassador was perhaps misinformed or deliberately misguided by his informer, but this story makes it clear that the US has at no stage abandoned its efforts to co-opt India into its strategic orbit.

A backward look in a divided polity

This book is in many ways unsatisfactory. The contextualisation of each dispute has generally been quite inadequate – particularly the two sections relating to post-Independent India. Here, it appears, the authors have not only sought to revisit the earlier discussions, but have placed themselves not as observers but as participants – their hostility to Nehru is palpable and generally unfair.

For instance, going beyond the matter of China, the authors’ statement that “one of major functions of Indian diplomacy then became the projection and protection of Nehru’s image as the champion of the Third World” is without foundation and betrays an ignorance of the values and sense of purpose, consensually held, that continues to drive Indian diplomacy. Ideas of non-alignment and, later, strategic autonomy, remain powerful influences on Indian foreign policy and impart a deep sense of confidence and pride to Indian diplomats.

One final cavil. If debates of nearly 80 years ago are to be revisited, should not an attempt have been made by the authors to provide, in a concluding essay, their assessment on where these issues stand today? Such an assessment would have, I believe, supported the validity of most of Nehru’s values, perspectives and principles – which far lesser beings are today seeking to demolish, with venom and violence.

Talmiz Ahmad, a former diplomat, holds the Ram Sathe Chair for International Studies, Symbiosis International University, Pune, and is consulting editor, The Wire.

This article went live on February seventeenth, two thousand twenty two, at zero minutes past eight in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.