The Nepal-Sikh Alliance That Could Have Changed History

Although it is not history’s job to dabble in ‘what-ifs’, could an alliance between the Gorkhas, the Sikhs and the Marathas have succeeded in ending the East India Company's machinations in the subcontinent?

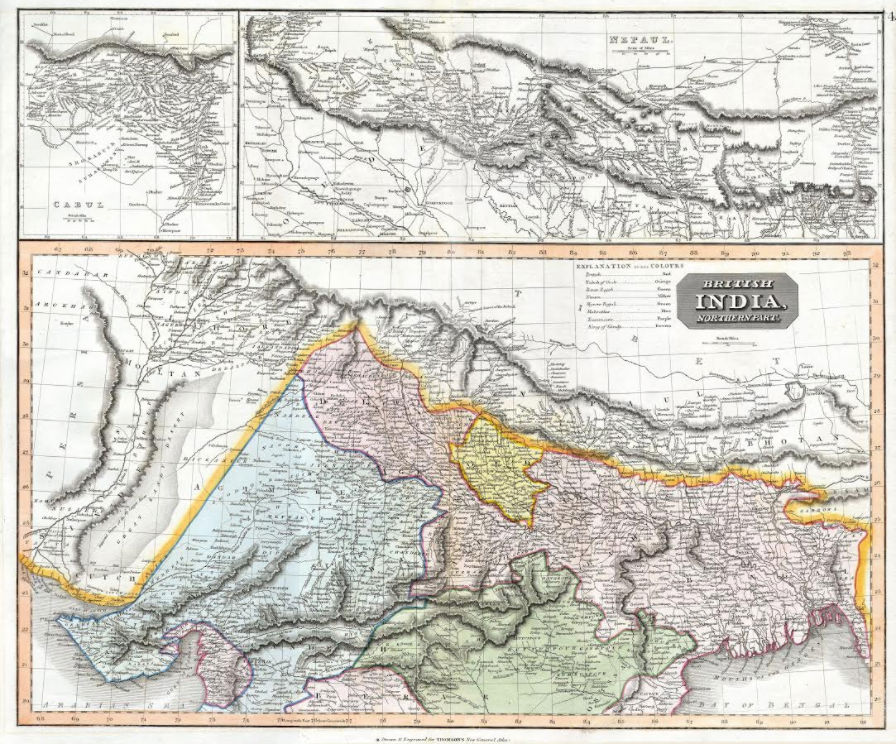

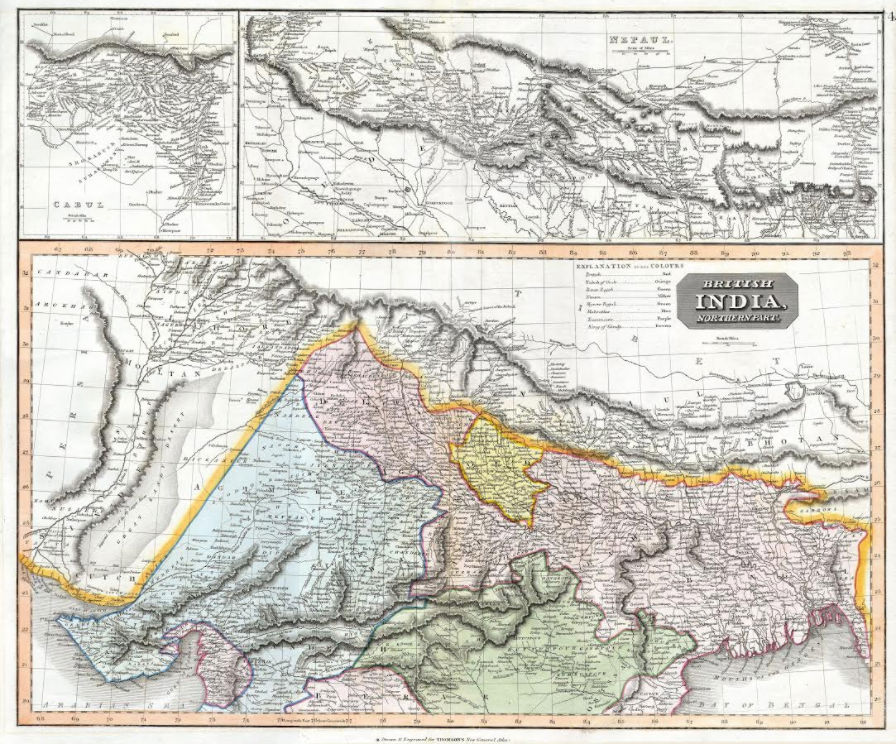

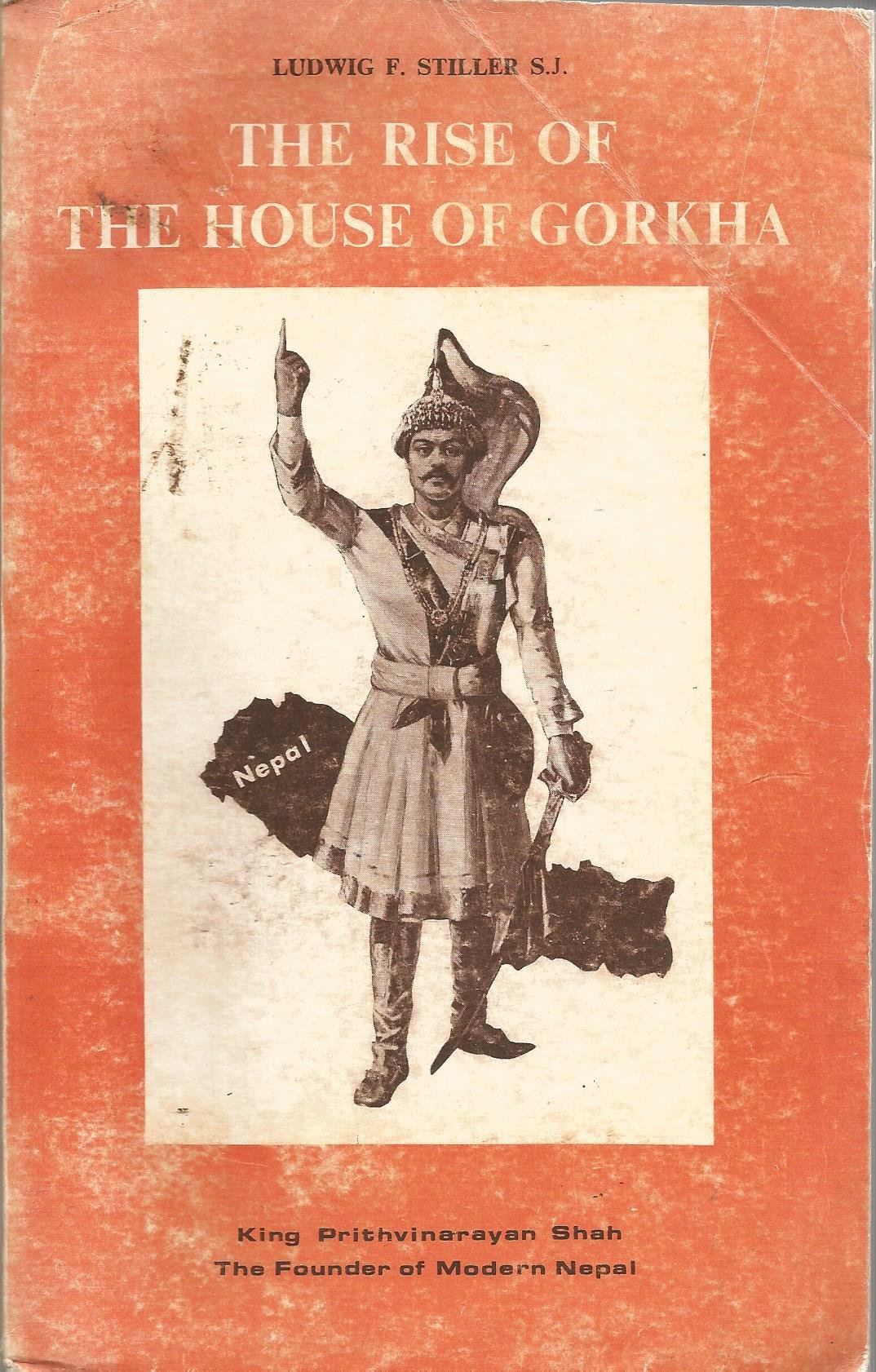

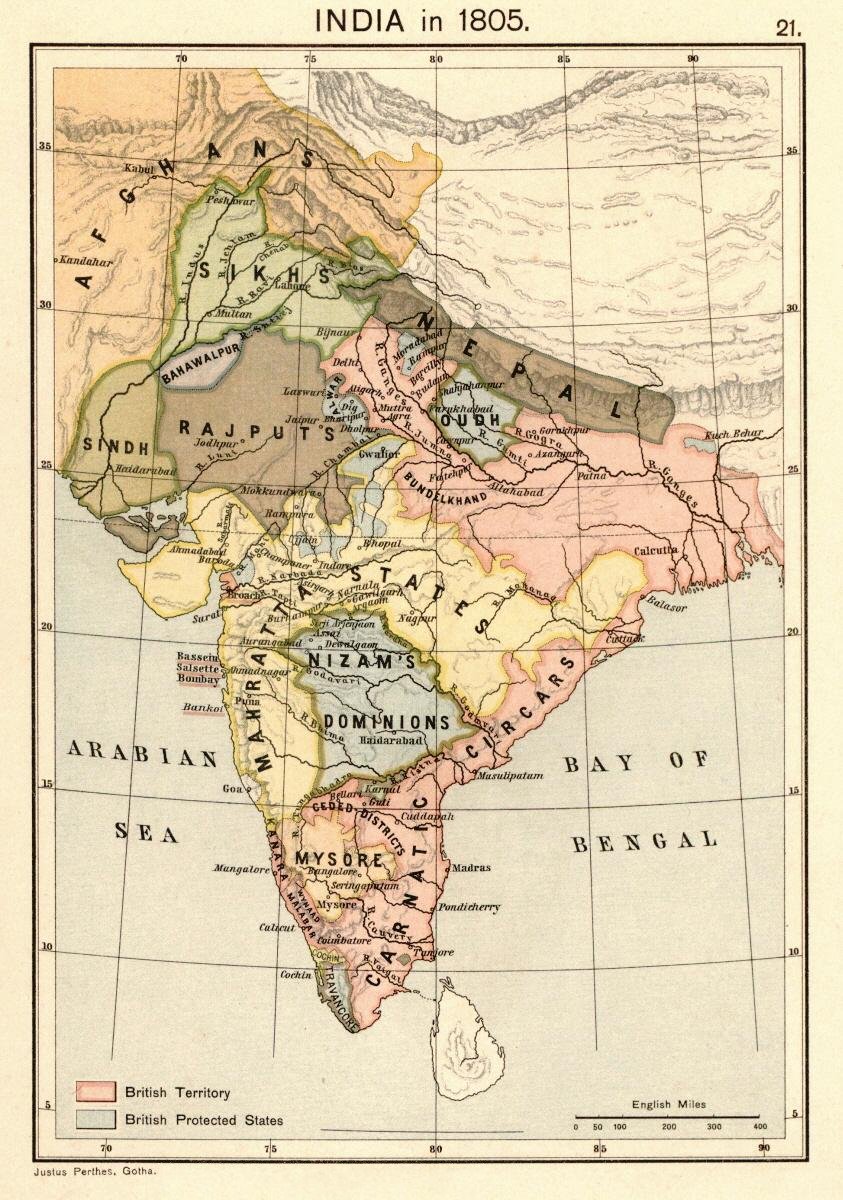

In the early part of the 19th century, a small settlement called Sugauli, in modern-day east Champaran, Bihar, was witness to a treaty that would shape the subcontinent’s history, and political boundaries. The House of Gorkha, the ruling Shah dynasty of the kingdom of Nepal, had sued for peace after suffering its heaviest defeat – the loss of its newly conquered territories of Garhwal and Kumaon – despite inflicting heavy damages on the East India Company in four other fronts. Although Nepal had to give up over 40,000 square miles of territory – Garhwal and Kumaon in the west; the kingdom of Sikkim, which the British had promised to return to the Chogyal; and land in the fertile Terai – the subsequent treaty, Jesuit historian Ludwig J. Stiller describes, "was the logical conclusion of the failure of...Kathmandu to insist on restraining the army’s westward march until an adequate and competent administration could be set up in the conquered territories."

I came across Stiller’s very readable history of Nepal, The Rise of the House of Gorkha (1973), earlier this year, two years after the infamous Indian blockade of Nepal, at a time when nationalistic pride is the new frenzy both in India and Nepal. As in the British era, Nepal’s kings (and politicians) have always looked south for continued support for their actions in the country. When it wasn’t coming, as witnessed by tacit Indian support to the Madhes movement and the 2015 blockade, Nepali politicians pushed the nationalist agenda, a harkening back to the supposed injustices of the Sugauli treaty (and the subsequent Indo-Nepal Treaty of 1950). A moribund political movement called the Greater Nepal Movement gains ground every time a dispute arises between India and Nepal, the latter accusing the former of not returning the territories it had conquered.

Stiller’s account, however, points to an intriguing line of enquiry. It begins with a letter that Maharaja Ranjit Singh, the founder of the Sikh empire, sent to Amar Singh Thapa, commander of the Gorkha military expedition west of the Sutlej, in August 1809.

Ranjit Singh had skilfully cut off Gorkha supply lines in their newly conquered territories east of the Sutlej and in Garhwal. The Gorkhas were trapped. "Had the Nepalese succeeded in reducing Kangra, there is little doubt that they would have very shortly after extended their conquest to Cashmere," a Captain C.P. Kennedy wrote in his Report on the Hill States in 1824.

Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s intervention in the Gorkhas’ military campaign had put a spanner in the works. The smaller rajahs of the hill states had been subdued by the massive Gorkha war engine that had already swept Kumaon and Garhwal, and was knocking on Kashmir’s door. Kazi Amar Singh Thapa offered to pay Ranjit Singh if he would withdraw his army, but Ranjit Singh himself had designs on Kangra. Instead, he wrote the Nepali general the 1809 letter, where he proposed, if Thapa withdrew from the area, the Lion of Lahore would cooperate with the Gorkhas against the East India Company.

Amar Singh Thapa refused to entertain Ranjit Singh’s missive, and even imprisoned the messenger, incensed by a treaty Ranjit Singh had previously signed with the Company in April that year. The letter, Stiller writes, struck him as ‘the height of hypocrisy’.

Thapa withdrew his forces after a fierce round of hostilities with Ranjit Singh’s troops. Five years later, the Gorkha empire would meet its most formidable opponent, the Company, all by itself.

§

The Shah king Prithvi Narayan Shah, who spearheaded the Nepali unification campaign, had fought against the Company in Sindhuli, Nepal, in August 1767. Captain George Kinloch led an ill-fated expedition that entered the Terai during the monsoons, when the aulo fever, malaria, was at its worst. Shah’s mastery of the terrain helped him beat back the British, but it was clear an uneasy truce had been struck. The Company would look the other way if the Gorkha war machine stuck to the hills, which it did, expanding relentlessly till Sikkim in the east, before it turned its eyes west from 1789 onwards, thus placing it irrevocably on a course of war with the Company. Stiller writes:

"The House of Gorkha and the East India Company had been on a collision course from the time that the Gorkhali advance to the west had placed them squarely athwart the trade routes [to] Tibet. Given the economics of the situation, the position of Nepal, and the British sense of their right (emphasis in original) to trade, there was no way of avoiding the war short of a complete and sudden reversal of character on the part of the Nepalese or the British."

War was coming, and the powerful Nepali prime minister Bhimsen Thapa knew it. But the Nepali army lacked the long-range cannons needed to besiege the Company, and wedged in by the powerful Ranjit Singh in the west and the Company to the south and the east, Bhimsen Thapa could not acquire "a better grade of steel and greater skill in casting" for his cannons. But there was still a card left to play:

"One of the key factors in Bhim Sen Thapa’s thinking was the recognition of the real weakness of the British position in India…[i]t was apparent to all that the Indian powers could drive the British out of the subcontinent if they could combine against them. But no one had succeeded in forming the type of confederacy that would be required for such a war."

In 1814, Bhimsen Thapa sent out missives, among other princely states, to the Marathas in Gwalior, where, although the Scindia was "impressed [by the Gorkhali courage] in standing up to the British", he agreed on allying with the Gorkhas only if Ranjit Singh joined the alliance. Amar Singh Thapa was required to send the Kathmandu missive to Ranjit Singh, which offered the Lion of Lahore: "a division of the Gangetic plain from Delhi to Calcutta between the Sikhs, the Gorkhalis and the Marathas…[and] an appeal to Ranjit in the name of Hinduism to drive the British out of India".

The tripartite alliance never came to be. One account suggests Ranjit Singh, like other Indian states, preferred to bide his time; also, that he turned "over to the British several letters that had been sent to him by Nepal" and mobilised his army to the Sutlej to take "advantage of any opportunities that might arise". Stiller suggests the Marquess of Hastings’ movement of over half of all Bengal army, ‘46,629 British troops’, to the Nepal front and ensuring the Marathas were up to no mischief by moving the "whole disposable force of the Madras army" to the northern border of Bhopal, scuttled any plans of such an alliance.

In any case, the moment was lost. Nepal went to war on five different fronts with the British between 1814-1816 before suing for peace, which resulted in the Sugauli Treaty that inextricably bound Nepal’s fate to the colonists, and after independence, to India. It lost all territory west of the Mahakali (or the Sharda, as it’s known in India), east of the Mechi and over half its territory in the Terai. The Gorkhas were now wedged in on three sides by the British or its protectorates, and on one side lay the impregnable Himalayas, their dream of creating a unified pan-hill state across the Himalayas halted in its tracks by a trading company.

§

By all accounts, the Gorkha empire was as opportunist as any other empire of its time, hungry for resources to fuel its massive army. Would it have stuck to its words had the proposed alliance come to be and they’d beaten back the British? We don’t know, considering the Gorkha empire’s sights were set on Kashmir, and so was the Sikh empire’s, but the alliance that could have been encourages a query: what if Amar Singh Thapa had acceded to Ranjit Singh’s initial request?

Although it is not history’s job to dabble in ‘what-ifs’, a query tickles the imagination – could an alliance between the Gorkhas, the Sikhs and the Marathas have succeeded in ending Company machinations in the subcontinent?

Amish Raj Mulmi is a Nepali writer and a publishing professional. He's currently digital editor at Juggernaut Books.

This article went live on May twelfth, two thousand seventeen, at zero minutes past six in the evening.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.