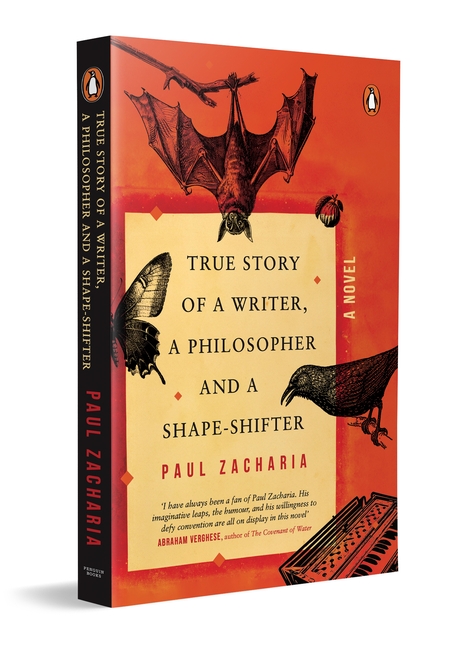

Paul Zacharia’s latest novel, True Story of a Writer, a Philosopher and a Shape-shifter, is a wink, a sleight-of-hand, and a meditation. A wink on account of the determined eccentricity of the characters and the loopy worlds that Zacharia situates them in. There is a hard-won authorial courage at work here, especially in an age when serious-mindedness afflicts great many. Instead, what we get is a novel that is determined to have fun, to let loose Zacharia’s comic and bawdy imagination into a metaphysical otherworld that few authors – especially one like Zacharia who remains singular in his intense and lifelong commitment to the written word – will find the courage to summon onto pages and sustain.

The peril however is that this wilful loopiness of the novel is deceptive – a card trick perpetrated upon the unsuspecting who may laugh and squirm, losing sight of the novel’s underlying ambitions. Thus, what we get, on the surface are sentences that roil between two ends – the author’s pen and the reader’s mind – all the while as the narrative periodically exhales the pleasure-poison of absurdity. But unlike our creation myths, there is no blue-throated God who appears on the scene to swallow this frothing and offer up an answer to that most unanswerable of all questions – what is this novel all about? This is an easy question to ask but harder to distil into an explanatory brew.

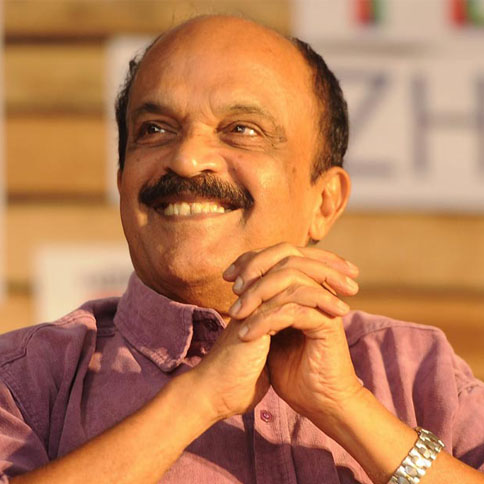

Paul Zacharia

True Story of a Writer, a Philosopher and a Shape-shifter

Penguin, 2025

On the surface, the novel is an episodic chronicle of Lord Spider, a 41-one-year-old fiction writer, who is tasked with writing a piece of non-fiction for an unnamed Revolutionary Party (no points for guessing this ideological hegemon that lumbers across Kerala’s politics and the Malayali mind). This setting is perfect for asking heavy-set questions that are the favourite of many a party politician who moonlight as intellectuals: in a world filled with politics, blood, ethnonationalism and class struggle – how must a novelist describe the world? If a novelist is deemed as a prophet of human destiny, how must he write about a future? What is the role of the artist at a time when all the valences of our collective and individual lives – love, justice, freedom, wealth – are elided and steadily eroded? These are the sort of questions that send a thrill up the thighs of party ideologues and intellectuals of Zacharia’s generation, especially in Kerala, as they slither up the stage with reptilian finesse for barn busting oratory. The result of their speechifying typically alternates between the terrifying and the assuredly soporific, and all the while party faithful sleepwalk from one public address to another as they collectively await an imminent but ever receding Revolution and, its perfumed henchman, the social Renaissance.

Thus, our novelist hero, Lord Spider, who is neither a Lord nor a spider, but rather an all-too-familiar figure of an author in search of inspiration and who is stuck in a rigmarole as a servile husband to an imperious wife, the philosopher Dr Rosi, meets an improbable amanuensis in the form a shapeshifting bat who in his human form is called Mr J.J. Pillai. Together the two of them – Spider and Pillai – seek to compose an essay with ample guidance and contribution from Dr Rosi. (On occasion, I wondered why Zacharia, who rarely shies away from mischief, didn’t call their intellectual output ‘the manifesto’, with all its accompanying resonances.)

In this kind of narrative framing, one recognises a familiar trope that writers from Vyasa in the Bhagavad Gita on down have relied upon wherein the plot unfolds courtesy the tensions and contradictions that emerge between a high-minded but dissolute protagonist stuck in a rut and the everyday cunning and transcendent wisdom of his improbable foil who offers a breakthrough. Thus, seeing the ping pong between Lord Spider and Pillai, one sees shades of Akbar and Birbal tales, Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, Jeeves and Wooster, the narrator and Alexis Zorba (in Kazantzakis’ Zorba the Greek), Ramakrishna Pai and Govindan Nair (in Raja Rao’s The Cat and Shakespeare), and even the letters of Marx and Engels. But what complicates this binary system of give and take walks is the presence of Spider’s wife who has her own mind and doesn’t hesitate to speak it. She has little use for this nonsense cooked up by these men, even if she is sympathetic to their adventures and is herself not averse to being puffed up by Pillai’s flattery. But the real complication, the serpent in this garden, is that J.J. Pillai is no ordinary squire to Lord Spider. Mr Pillai wants to be a writer too.

On various occasions, we come face to face with the melancholy truth that Zacharia suggests but never instructs – that the act of writing is an individual’s struggle with himself, and the world of politics is its antithesis that manifests as a collective hallucination. And when the two worlds meet, flirt and couple in the bed of compromises, they birth a monstrous form of writing that is part self-fulfilling prophesy and part propaganda. Zacharia invites us to witness the birth of one such abomination.

This is perfect material for a writer to offer up homilies and moral instructions for our witless times. But thanks to Zacharia’s determined effort to avoid pontification, he sees society, its mores and his own alter-ego (a novelist protagonist) as a site for mockery and reflection. The result is we, the blessed reader of this madcap novel, are subject to various clever, suggestive and inspired segues wherein men become avian creatures, bats metamorphose into men, Satan brushes his teeth mid-air, and Jesus is involved in a complicated and unexplainable routine in Tamil Nadu. I laughed as I turned the pages, not only because of Zacharia’s sly matter-of-fact descriptions but also because I could see India – that ever engorging and all corroding boa constrictor – transmuting biblical foreign bootleg into our local variety of intellectual arrack. It is a testament to Zacharia’s genius for observing this deep truth about India that allows for these waves of recognition to shimmer in a reader. All of this is courtesy his manic energy, a determination to be non-serious even if on occasion jokes are forced, that pulsates through the pages, as if Zacharia were laughing all the while as he wrote up these lucid absurdities.

Paul Zacharia.

An unsuspecting reader, who has read little of Zacharia over the years (his first short story ‘Unni enna Kutty’ appeared in 1964, in the Mathrubhumi magazine), may conclude that Zacharia has gone mad in the 79th year of his life. But writers who go out on a limb, especially those with a reputation for seriousness, are prone to such suspicions. When Emerson published his poems, we are told, The North American Review asked, “Is the man sane who can deliberately commit to print this fantastic nonsense?” But on closer inspection, once Zacharia’s novel ends and the ongoing suspicion of what-the-hell-am-I-reading abates, and when the words and scenes have settled down in the subterranean worlds of a reader’s mind, the underlying conceits and ambitions of Zacharia’s novel reveals like some cosmological koan. This recognition laughs at our own despair as we realise that the novel, in its deepest sense, meditates upon the very (unnatural and, yet, all too human) act of writing and all that flows from it.

Among the novel’s various running themes, one of them is the obsequiousness of a wannabe writer who, as it turns out in Pillai’s case, knows more (at least, theoretically) about the art of writing than Lord Spider himself. This mastery of second-hand knowledge ought to come as no surprise to anyone who has observed the Indian variant of this phenomena. We see this effort to be authentic by mimicry among religious converts and political ideologues who spend their entire lives emulating an ideal which is indistinguishable from an illusion. But Zacharia’s Pillai is not just an empty shell. He is a raconteur whose stories begin from the impossible and metamorphose into the insane. He is Kafka on acid.

Thus, we hear early on that Jesus was a young man living in Papanasam, near Tirunelveli, and later, we discover that when the much-feared Stalin – the Lord-of-the-Gulags – disrobed, there stood a woman ‘down to her last detail’. Jesus the Tamilian, Stalin the cross-dresser and so on – the novel is peppered with many such wonderfully outlandish images including a final aerial flight of the birds that reminds one of Fariduddin Attar’s The Conference of Birds. As any reader of Zacharia’s writings and life as a public intellectual who refuses to play ball with progressive and conservative pieties of Kerala’s social life will recognise, these throw away details – the garnish over the main course – undermine the two bête noire of his life, the convenient hypocrisies of organised religion and the authoritarian violence of political parties.

What thus animates the novel’s glee filled rage is Zacharia’s instinct to cut down the pomposity of the powerful – including his own alter-ego – while still recognising that the weak (Pillai, in here) are just as capable of cunning as well. To this end, he returns time and again to the image and metaphors that have come down to us via the great religious traditions, treating them as props to aid the description of the human experience. This is not just an aesthetic in service of a comic novel but is also an attitude towards life, a form of a skeptic’s intelligence at work, a humanist’s suspicion of his own progressive shibboleths and much claptrap that is trafficked in the name of tradition.

Of the three characters who fill this voluble threesome, arguably, the most real and therefore the most underwritten is the wife, Dr Rosi, who is the philosopher in the novel’s title. She is gentle in her disposition but stern in her opinions – anyone who has known Malayali matriarchs will recognise this variety of the human species instantly – and has the assigned role of bursting the pomp filled writerly-bubble of Lord Spider and interrogate the mythomania of J.J. Pillai. And in more intimate matters with Lord Spider, she is cool towards his erotic ministrations – because of which, or perhaps despite it, sex is never far from Lord Spider’s mind. In a passing tryst with a character called Sister Molly Magdelene, she holds Lord Spider’s nakedness in her palm, and says, ‘From today, you are like Jesus to me.’

Together, the three of them – a novelist wracked by self-doubt, his wife who embodies a sensual omniscience, and a shapeshifting phantasm who aspires to be a short story writer – present a three-body problem with no equilibrium in sight. The trio are built differently, their life goals – confidence, renown and insight – are orthogonal to each other, and never will they find harmony except in this temporary denouement in the form of a political essay with which this book of follies and frolic ends.

Zacharia, as a writer of acid-tongued columns in newspapers, has seen up-close generations of self-aggrandising politicians who have ravaged our body politic like some pestilential sore. The result is that he turns these questions of the kind they would ask inside out. What matters is not the answers, he seems to suggest, but how we get to the answers, howsoever provisional it may be. And much as the apocrypha attributed to Bismarck warns about the perils of inspecting the sacred too closely lest we lose our sense of sanctity for it (“Laws are like sausages. It is best not to see them being made.”), Zacharia’s novel wades into the very making of ideological and bombastic statements by intellectuals on behalf of political parties.

Once the reader sidesteps the various subplots that seek to distract and seduce and confound, what remains are Zacharia’s meditations on the craft of writing, meditations on the impossibilities of rendering experience onto the pages, and in the final reckoning meditations upon facing the most implacable enemy of every writer – the blank page. Far removed from the haze and light of Zacharia’s energies, we realise that he has inverted the often-pedestrian piece of political writings that appear in the form of editorials and essays in our newspapers and magazines by asking instead how it is all put together. The answer he proffers is not a political screed or an effort to excavate some ur-form of ideological commitments.

Instead, Zacharia uses it to dwell on themes he has no doubt thought often about in the past. And the answer, in so far as one can decipher from this novel, is not a happy one or even weakly comforting. Most writers, it seems Zacharia is saying, despite their pretensions on social media and public pronouncements at literary festivals, have little idea of how to go about the very act of writing. It is a game of wrong starts and perseverance, wild turns and rapid shifts in register, all the while as some large narrative architecture takes shape. But no writer can do it alone – even if much is made about the solitudinal figure of the author in our contemporary discourse. To this end, Zacharia’s novel tells us that some dosage of reason and restraint (in the form of Dr Rosi) and a fistful of irrational inspirations (a role that Mr J.J. Pillai plays) need to come together to aid the quiver and tremble that thrive inside a writer when he sits in front of an empty page.

Zacharia has had an illustrious career as a short story writer, essayist, novelist and travel writer – what runs common through them is his commitment to to see the world without the blinkers that come naturally to one and all, including in his case as one born into a Malayali Christian cultural context and as one who has had little use for the Church’s hegemonic presence, as one who has ridiculed the Church’s commercial and liturgical overreach in our secular times, and as one who has periodically found new enemies. (His enemies, over the years, have ceased to argue since they now stare vacantly from burial grounds or crematoriums, while he still goes on, sprightly, curious and full of literary ambition.) But to reduce Zacharia into some sort of gadfly is to overlook his masterly talent for transmuting human experience and hypocrisy and self-loathing into a language that reveals the untruths that men tell each other to make life bearable. In this he has been unsparing in his entire oeuvre.

Zacharia has no use for language that makes life bearable. Life, he has time and again shown in his writing, is an unbearable absurdity. The only question is can we make some art out of it and throw some light upon the human experience. And laugh while doing so, as we do repeatedly when reading this slender work that hides its wisdoms on the surface and refuses to take itself seriously. There is a lesson in there somewhere. A lesson Zacharia refuses to describe as one.

Keerthik Sasidharan is the author of The Dharma Forest and lives in New York City. On X, he is @ks1729.