Prabir Purkayastha Memoirs: An Unbroken Commitment to Rationalism, Scientific Temper and Justice

The memoir of Prabir Purkayastha, political and science activist and founder of the digital news portal NewsClick, includes a vivid and stirring account of his incarceration during the Emergency of 1975-77. A grim irony is that this was published barely days after his fresh incarceration by the present regime.

This time, his arrest was for charges under a terror law.

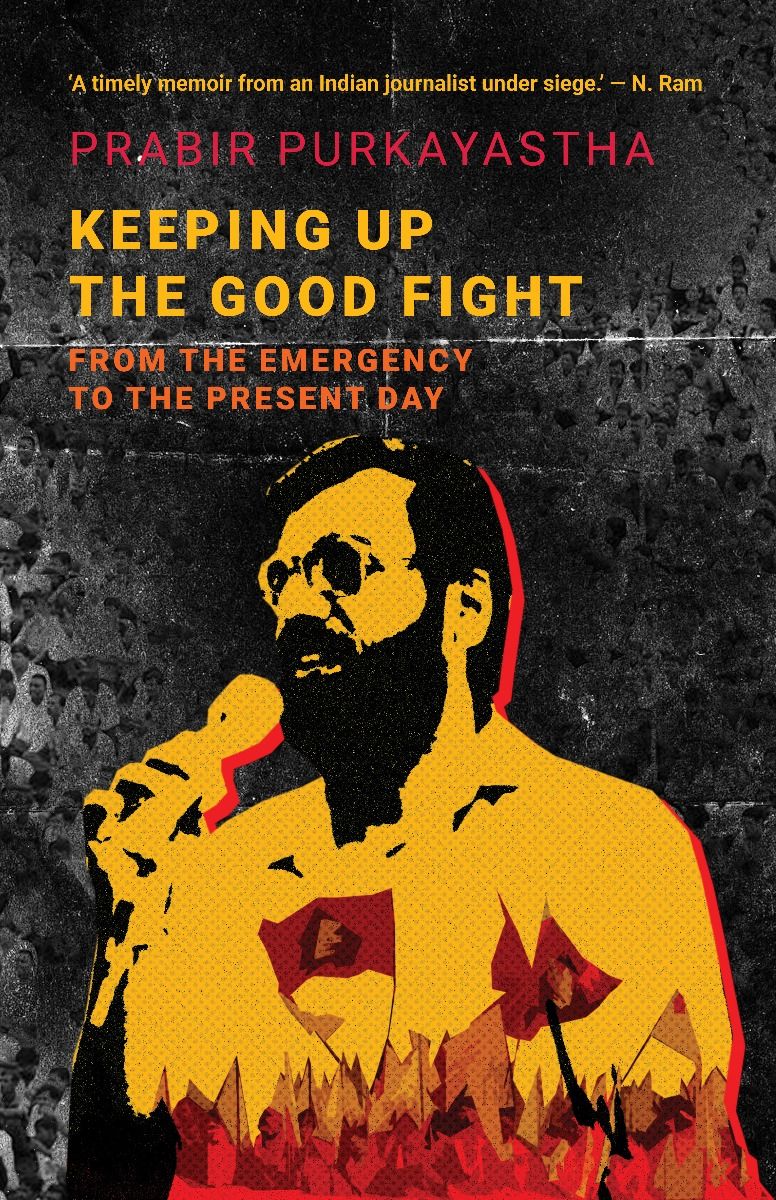

This is only one of many reasons that makes Prabir Purkayastha’s Keeping Up the Good Fight: From the Emergency to the Present Day compelling, indeed necessary reading.

For millennials born after India’s epochal transformations with the neo-liberal restructuring of the economy and the rise of majoritarian politics with the Ram temple movement, Prabir’s record offers an instructive window to a time of nation-building that they never saw, a time of upheaval, resistance and hope, when young people in universities, unions and people’s collectives were convinced that a better world is possible, and that they would be part of making this happen. His account stirs nostalgia among many like me who grew to adulthood through these more idealistic times of both the erecting and contestations of a new nation coming of age from the decades of the 1960s onwards.

§

By any measure, Prabir’s is a remarkable life. But his own recounting of it in his memoir is characteristically low-key. Unlike any number of similar chronicles, he never foregrounds his own remarkable courage and steady idealism or his many significant accomplishments. He prefers instead always to focus on public issues and challenges, and to the contributions of many others who pass through his life. But despite his restraint and modesty, what still shines through the pages of this slim dossier of his life’s work is his unbroken commitment to rationalism, scientific temper and justice for the country’s most oppressed people.

Prabir Purkayastha

Keeping Up the Good Fight

LeftWord Books (October 2023)

Prabir describes briefly a somewhat lonely childhood: his father, an officer of the Indian Revenue Service, was transferred too rapidly from city to city to make lasting friendships possible for Prabir. His early great love was for books, with a relish for adventure stories, detective fiction and historical romances. It was during his childhood years that he was also drawn to science and maths, and he also developed a scepticism about religion and God, laying the foundations for a life-long atheism.

Prabir speaks of the three driving forces of his life – science, technology and politics.

Of science and technology, his commitment is first to making scientists and technologists accountable to ordinary people. This calls for both the demystification of science and popularising its social dimensions. Next is the promotion of scientific temper. The third is to fight the linkage of scientific and technological research to private profit. And fourth is the promotion of self-reliance in science and technology to decolonise scientific knowledge and free India from dependence on rich and industrialised countries. These together formed the core of his contribution to various popular science movements.

The mass killings of Sikhs after the assassination of Indira Gandhi in 1984 and the movement for the demolition of the Babri Masjid also drew Prabir inexorably into movements to defend secular democracy and the rights of religious minorities.

§

But what drove his life most was his politics. His politicisation began in university after he joined the Bengal Engineering College. He recalls this to be a time of ferment – the war in Vietnam, students in Paris occupying the campuses in 1968, the food movement in Bengal, and student protests, all of which helped mould his political consciousness.

He was captivated by the writings of Marx: he recalls a “gooseflesh moment” when he first read The Communist Manifesto. He was drawn to Marx’s intellectual framing of problems rather than liberal romanticism. He describes also how Vietnam inspired him as a “powerful symbol of resistance”, this “completely unequal struggle of the Vietnamese people against the biggest military power in the world…”. He underlines that when Marx spoke of the role of force in history, he did not necessarily endorse violence, but instead the coercive power of oppressed classes.

He describes in his memoir his early resolve, as an engineering student, to support and eventually join the Communist Party (Marxist), the CPI(M), and his steady commitment to the party throughout his adult life. The moment of choice came when he heard Hare Krishna Konar of the Kisan Sabha speak. The Sabha was organising land struggles including to forcefully occupy surplus lands. He explains also why he rejects other dominant streams of the Left – the Maoists and Naxalites, the Trotskyites and the CPI (which incidentally supported the Emergency and believed that the Congress would lead the country to an Indian variant of socialism).

After graduating, as he lived in Kanpur with his parents for some months, he drew close to local party and trade union leaders. It is in his Kanpur days that he also learned to accept comrades whose political views he might disagree with. While some in the Left are quite sectarian, while Prabir holds strong political views, he is always open to working with, respecting and trusting people whose commitment to progressive values he recognises, even though he might disagree with their political alignments. The yardstick he would apply lifelong in choosing his comrades is this: What side of the larger class struggle is the person on?

He joined an engineering college in Allahabad for his Master’s degree. Student politics in Uttar Pradesh he found to be very different from Bengal and Calcutta. These were marked by muscle power and caste in ways that he had not encountered earlier. The party in Kanpur was very weak. Prabir would try to engage students with discourses in understanding the violence that our society inflicts on the poor which people of relative privilege do not register.

It was his research quests that transported him to Delhi, a relocation that was destined to be the most decisive turning point in his adult life. He initially reached out to work with leading scientists at the Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi. But all his leisure time, he spent in the canteens and lawns of Jawaharlal Nehru University. He loved JNU, its friendly welcoming climate, the diversity of class and region of the student population, the ease with which men and women students related with each other, the comfortable relationship of the faculty and students very different from the rigid hierarchies of Uttar Pradesh, and the rich debates between various streams of Left politics. His descriptions of his years in JNU rouse an immense wistfulness for a space that was egalitarian, intellectually robust, politically vibrant and encouraging of critical thinking and debate, especially because under the current regime, all of this has been systematically decimated.

It is in JNU that Prabir met Ashoka, the woman he loved and married, a fiery student leader. These are again the few pages that he allows himself to dwell on his personal life, how the young couple had to negotiate family prejudices on both sides, to insist on a civil marriage with no religious ceremonies, and how their marriage was interrupted for many months by Prabir’s sudden arrest after the Emergency was imposed on the country. And later their marriage, their happiness as they lived in a single-room apartment dividing domestic responsibilities, the birth of their first child, and finally the thunderbolt of Ashoka’s sudden death at the age of 31, leaving Prabir desolate and a single father for their newborn son.

§

Prabir’s description of the Emergency and the fear and repression that it unleashed is a significant part of the memoir, in which he bears witness to the 18 months in which democracy was suspended. He relates how – mistaken for the president of the JNU Students’ Union – he was arrested and jailed.

His accounts of his year in prison – first in Tihar and later in Agra – are some of the most riveting in the book. The highly divergent political groups that fought the Congress led by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi were lumped together in the prison barracks – from the RSS and BJP at one end, to the various streams of socialists, to the breakaway Congress, to the CPI(M). Prabir describes how he divided his time between political debates, reading and cooking (ineptly) in the jail kitchen; and how they looked forward to the mulaqats or meetings with family – Ashoka mainly came, and sometimes his parents – where inmates would scramble together news of the country and if there was resistance and popular dissatisfaction. What marks out Prabir’s jail narratives – including of a period of solitary confinement and a hunger strike – is again a singular absence of both self-pity and bravado.

Representative image. Photo: Tum Hufner/Unsplash

§

In the opening pages of his memoir, Prabir fast forwards to the present, to February 9, 2021, when his Delhi home was raided by the Enforcement Directorate. The raid continued for 113 hours. The months that followed were packed with innumerable interrogations and court hearings. Prabir responded again with his characteristic courage and resolve, unwilling that the authorities damage his morale or halt the independent reporting of NewsClick.

Prabir asks poignantly: Does every generation have to face an emergency? He speaks of the markers of this undeclared emergency, still unfolding as he writes, of “the hatred-driven hounding and trolling, the assaults, the detention, the spurts of violence, and above all, the fear”. He describes the murder, jailing and official discrediting of rationalists and secular activists, the changes in citizenship laws creating an implied hierarchy of citizenship based on religion, the repression of the heroic farmers’ protests, and the soaring of hate speech and lynching. The first emergency had much of this – the fear, the silencing of dissent, the muzzling of the media and the courts. But there is one critical difference, Prabir notes. “The Congress ideology,” he observes, “did not view certain sections of the people as outsiders, to be treated either as second-class citizens or excluded from citizens’ rights”.

The book was probably at the printing press in its last stages of printing when its unwritten epilogue was crafted. On October 3, 2023, officers of the Special Cell of the Delhi Police arrested Prabir and his colleague from NewsClick under the dreaded anti-terror law, the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967, which makes bail extremely difficult and shifts the burden of proof on innocence on the accused.

Also Read | ‘The Difference Between Then and Now’: Prabir Purkayastha on Emergency and the Modi Years

§

I read his words again and again. “Living politics needs,” he reminds us, “a firm commitment to struggling for equality.”

All the while as I hold his book in my hands, and as I write this account of why the book is necessary reading to understand our times, I am haunted by the image of Prabir, now 47 years older than when he was first jailed in the Emergency of 1975-77, once again in prison, feebler in body, challenged by serious health ailments, but as blameless, as resolute and as brave as the first time.

His continued incarceration diminishes us all.

Harsh Mander is a social worker and writer.

This article went live on November twenty-sixth, two thousand twenty three, at forty-six minutes past eleven in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.