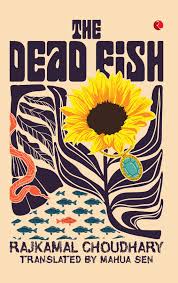

'The Dead Fish': Why Rajkamal Chaudhary’s Unsettled Modernism Endures

Rajkamal Chaudhary has always been a difficult presence in Hindi literature. A restless figure who lived only 37 years, he wrote poetry, fiction, reportage and even film scripts, with an impatience that reflected the urgency of post-Independence India. He belonged to no school, was suspicious of sentimentality, and wrote with a raw directness that unsettled his contemporaries.

Machhli Mari Hui (The Dead Fish), first published in 1966 and now available in English in Mahua Sen’s translation, remains his most controversial novel. It was the first Hindi work to openly deal with same-sex desire, particularly lesbian relationships, and confronted, without disguise, the hypocrisies of urban modernity.

To read this novel now is to be reminded how radical it was in its time, and how uneasy it still makes us.

A city, a man and a wound

The novel unfolds in Calcutta, a city Chaudhary knew well and depicts with industrial precision. His Calcutta is not the genteel city of poets but a place of steel, skyscrapers, cheap boarding houses and smoky cafés. It is a city that stirs restlessness in its inhabitants.

Rajkamal Chaudhary, translated by Mahua Sen

The Dead Fish

Rupa, 2025

The protagonist, Nirmal Padmavat, is a man of contradictions – an industrious businessman, hardened by commerce, yet marked by emotional fragility. He once loved Kalyani, but she marries another man, Dr Raghuvansh, and their daughter, Priya, becomes an inadvertent reminder of his wound. This triangle – Nirmal, the lost Kalyani and the symbolic presence of Priya – forms the novel’s psychological core.

When Priya brings into her orbit Shireen, a strange, neurotic friend, the novel changes register. Shireen is described as a woman adrift, a ‘dead fish’, her desires thwarted, her homosexuality unacknowledged, her existence suspended between numbness and hunger.

The first lesbian character in Hindi fiction

It is difficult to overstate the audacity of Chaudhary’s choice. In the mid-1960s, Hindi literature had barely begun to discuss sexuality in heterosexual terms, let alone depict lesbian desire. Same-sex relations were either invisible or dismissed as ‘Western imports,’ a view repeated by conservative critics well into the 1980s. Chaudhary broke that silence.

Shireen’s presence is not symbolic decoration: she is the novel’s unsettled conscience. She is restless, hungry and often written with a clinical harshness that reveals the author’s own conflicted gaze. Some scholars have accused the novel of lesbophobia, noting that Shireen’s sexuality is depicted as neurosis or sickness. There is truth in that charge. Yet, one must also recognise the significance of her very visibility. By writing her at all, Chaudhary marked a rupture in Hindi fiction.

The metaphor of the “dead fish” is crucial here. It suggests a life half-lived, suffocated, yearning for water yet condemned to dryness. In the novel’s haunting final passage, a rain shower briefly revives the dead fish, suggesting that compassion, however fleeting, can restore breath. It is an ending both elegiac and ambiguous: neither redemption nor doom, but a recognition of life’s stubborn will.

The abrupt modernist

Readers accustomed to the lush prose of Hindi realists will find Chaudhary’s writing sparse, almost abrupt. His style is unadorned, yet strangely piercing, closer to reportage than to lyrical fiction. In this he appears impatient with illusions, unafraid of exposing weakness, unwilling to comfort.

Characters in The Dead Fish are not rounded personalities but fractured beings. Nirmal’s ambition is always undermined by his unhealed longing for Kalyani. Kalyani herself is drawn with a coldness that denies her the easy role of muse or betrayer. Shireen, meanwhile, is all nervous edge, resisting assimilation into the social world. None of them are offered redemption; Chaudhary refuses the neat moral arc.

This refusal is precisely the novel’s modernist strength. It dramatises the dislocations of an India in the 1960s, urbanising fast, absorbing Western ideas, yet still shackled by social hypocrisies. Desire is expressed but never fulfilled. Empathy flickers but rarely sustains.

Translation as excavation

Rajkamal Chaudhary.

Mahua Sen’s English translation deserves notice. Chaudhary’s prose is deceptively simple, but its rhythm is particular: short sentences, abrupt shifts, sudden images. Rendering this into English without smoothing away its jaggedness is no easy task. Sen succeeds in preserving the starkness, even if certain passages inevitably lose the idiomatic bite of Hindi.

The greater achievement of the translation, however, is historical. It excavates a forgotten text, making it available to a global audience at a time when queer literature in India is finally claiming recognition. What might once have been dismissed as pathological can now be read as testimony, evidence of how desire was written, distorted, suppressed, yet still present.

The novel in context

The Dead Fish is not an isolated outburst but part of Chaudhary’s larger project. He belonged to the ‘Nayi Kahani’ (New Story) movement of the 1950s and 60s, which sought to depict the alienation of middle-class life with new honesty. His contemporaries – Mohan Rakesh, Kamleshwar, Nirmal Verma – were experimenting with form and theme, but none matched Chaudhary’s fearless treatment of sexuality.

Beyond Hindi, Chaudhary’s novel resonates with other world literatures of disquiet. One thinks of Jean Genet, whose homosexual characters inhabited the margins of French society, or James Baldwin, who wrote of same-sex love in an America hostile to it. Closer home, Ismat Chughtai’s Lihaaf (1942) had already hinted at lesbian desire in Urdu, but Chaudhary’s novel was the first in Hindi to bring it into the open.

More than half a century after its publication, The Dead Fish is still not easy to read. Its depiction of lesbianism as neurosis can offend readers; its characters’ jaggedness will unsettle others. But its importance lies in its refusal to conform. Chaudhary dared to write what most of his peers ignored. He exposed the fractures of middle-class life, the loneliness of men, the restlessness of women, the suffocation of queer desire.

In our present moment, when queer voices are reclaiming space in literature and politics, this novel re-enters with a different resonance. It is no longer ‘shocking’; it is also a document of repression and survival. Its metaphors remain powerful because they speak to lives still lived in shadows.

Chaudhary died in 1967, leaving behind an unfinished body of work. Had he lived longer, he might have reshaped Hindi fiction more decisively. Yet even in his short career, he carved a reputation as one of its most uncompromising voices. The Dead Fish is proof of that courage.

The novel is unsettling, at times crude, but never dishonest. Its metaphors of deadness and revival, its fractured characters, its abrupt prose, all bear witness to a society in transition and a writer unwilling to look away.

To revive this book now, in English, is not only to restore Chaudhary to our attention but also to recognise that the histories of Indian modernism are not neat, nor polite. They are jagged, like the lives they describe. And in that jaggedness lies their enduring truth.

Ashutosh Kumar Thakur is a management professional, literary critic and curator based in Bengaluru.

This article went live on August twenty-ninth, two thousand twenty five, at thirty minutes past eight in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.