Remembering Charles Correa’s ‘Architecture for Argument’ Plans

The following is an excerpt from Charles Correa: Citizen Charles (Niyogi Books, 2024), the first biography to be written on the architect, urban planner and film-maker.

In 1973, Charles Correa prepared a proposal for an alternate residence for the Prime Minister of India. Located in Mehrauli, Delhi, this new second home, or retreat was intended to function as an Indian ‘Camp David’. This would be a contemplative space, where the Prime Minister (Indira Gandhi, at the time) could convene with Heads of State for more informal (and perhaps more significant) parleys, about the country and

the world.

Charles Correa: Citizen Charles, Mustansir Dalvi, Niyogi Books, 2024.

Here he chose to rework an un-built design for a farmhouse for the Sen Family in Kolkata, by arranging a range of ‘caves’ or cells around a square courtyard, recalling a Buddhist Vihara, or the cloisters of a Gothic Cathedral, but built with the simplest of Indian materials, mud and bamboo. This frugality was an indicator to visitors about the importance of simple living and high thinking, and also a demonstration of how an important government edifice can relate with village homes, and those of the poorest of the poor in the country.

‘The fall-out,’ Correa wrote, ‘from such a project would be manifold:

a. It would perhaps be a more realistic place to come to grips with India’s problems than the corridors of Imperial Delhi.

b. It would create the ideal “ambience” for a think-tank.

c. It would give the state visitors a unique and unforgettable experience of India.’

While the cells were private spaces or suites, it was important that the dignitaries should emerge into the enclosed square courtyard for their important confabulations. The courtyard, for Correa was at once a primal image/space, as much as a viable contemporary place for a variety of functions. Correa hoped this building would act as a role-model, or ‘a catalyst, in introducing into our society a much simpler way of life.’ In many ways, this design was reminiscent of the Gandhian principles which had informed his work at the Sanghrahalaya. The manner of building envisaged, with local construction materials and labour, also mirrors the honest labour of cottage industry, of which Gandhi was a lifelong advocate.

Sketch on page no. 34, Archaeology Museum, Bhopal (1985): copyright Charles Correa Associates, courtesy Charles Correa Foundation.

It is unclear whether this proposal was appreciated by those in power, but it remained on paper, a building as an idea. Was Correa expecting too much of the ruling establishment two decades after Independence? That they would still follow the path of the Father of the Nation? Was there a certain naïveté to his vision?

On several occasions in his career as an architect, Correa would encounter resistance with ideas that pushed the envelope of public acceptance, whether in his additions to Rajghat, or providing for the homeless on the streets of Bombay, or indeed his proposal for what should be built at the disputed site at Ayodhya, after the Babri Masjid was wantonly demolished in 1992.

Deeply secular, Correa was disturbed enough by the events in India in 1992-93, particularly the communal bloodletting in Bombay, to offer a proposal for peace through architecture – an alternative for the disputed site at Ayodhya, where once the Babri Masjid had stood.

He sought to unite fractured minds through an ‘un-building’, and chose a primordial form that sank a few levels into the earth, rather than rise up to monumentality and aggression. This design, too was about landscaping and climate as much as architecture. Through this, he conveyed an ‘architectonic symbolism,’ which showed how much all religions have in common.

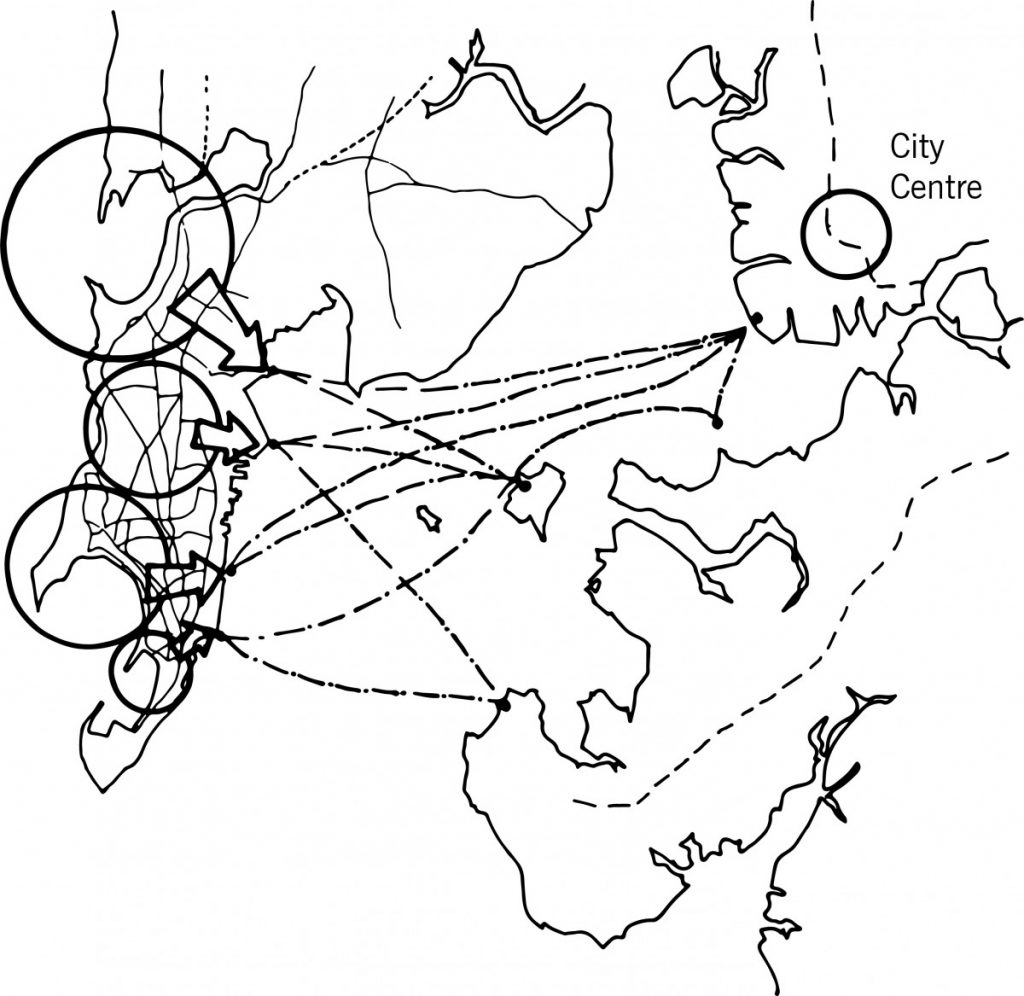

Sketch on page no. 108, Planning for Bombay (1964): copyright Charles Correa Associates, courtesy Charles Correa Foundation

‘Bombay, originally was the finest of things: a city on the water. From this grew its character.’ - Charles M. Correa, Pravina Mehta & Shirish B. Patel, ‘A Master Plan for Bombay,’ The Times of India, March 29, 1964.

This space, with a plan that was formed by a cross overlaid on a square, sank like a stepped-well, like the kund at Modhera. But at the same time, its empty centre reminded the observer of a Mughal Charbagh, with the water-fountain at its centre. The ‘axis mundi’ rose intangibly from its centre recalling a Buddhist stupa, the oculus of the Roman Pantheon, and the Bramha-sthan of the Vedic vastu-purusha-mandala. By not building, the un-manifest was made manifest. This entirely outdoor project would bring people of all faiths together into the bright light of day, and soothe their brows with breeze cooled by a central water-body.

In the proposal for Ayodhya, like the design for the PM’s think-tank, we see Correa’s ‘architecture as argument’, not necessarily intended for building, but for provoking discussion, and perhaps changing our ways of seeing. In both projects, the courtyard begins as a climatic device and then starts to garner a deeper signification as an empty centre, devoid of form but full of possibilities.

Mustansir Dalvi teaches architecture in Mumbai. A PhD from IIT-Bombay, Dalvi is also a published poet and translator.

This piece was first published on The India Cable – a premium newsletter from The Wire & Galileo Ideas – and has been updated and republished here. To subscribe to The India Cable, click here.

This article went live on October third, two thousand twenty four, at fifty-one minutes past nine in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.