Revisiting Rabindranath Tagore's English Gitanjali and its Bengali Original

Rabindranath Tagore died on this day in 1941.

Where the mind is without fear and the head is held high;

Where knowledge is free;

Where the world has not been broken up into fragments by narrow domestic walls;

Where words come out from the depth of truth;

Where tireless striving stretches its arm towards perfection;

Where the clear stream of reason has not lost its way into the dreary desert sand of dead habit;

Where the mind is led forward by thee into ever-widening thought and action –

Into that heaven of freedom, my Father, let my country awake.

That, inarguably, is one of the most commonly-cited poems from Rabindranath Tagore’s Gitanjali: Song Offerings, maybe from his entire poetical oeuvre, even. Readers who are familiar with the poem’s Bengali original are aware that the English poem was derived from a sonnet which features in Tagore’s 1901 book of poems titled Naibedya (‘Offerings’) – a sonnet not in the Petrarchan or the Shakespearian mould but in the form that Rabindranath made his own, comprising seven rhyming couplets. In its mutated shape, let’s admit it, this poem does look more than a little unfamiliar to a native speaker of Bengali. And, regardless of whether she reads Bengali or not, every reader of this poem will likely puzzle over its finished form when she is told that this is how the poem originally looked in Tagore’s own translation:

Where the mind is without fear and the head is held high; where knowledge is free; where the world has not been frittered into fragments by narrow domestic walls; where words come out from the depth of truth; where sleepless striving stretches its strenuous arm towards perfection; where the clear stream of reason has not lost its way in the dreary desert sand of dead habit, and where the mind is led forward by thee into ever-widening thought and action – there wake up my country into that heaven of freedom – my father!

So how did a free-flowing single-paragraph prose poem get broken up into as many as eight stanzas (albeit single-sentence stanzas)? Admittedly, there are only a few changes in words or expressions from one version to the other, though a couple of those changes – notably in the last line/stanza and the substitution of ‘broken up’ for ‘frittered’ and of ‘into the dreary desert sand…’ for ‘in the dreary desert sand…’ are happy emendations.

But overall, can we say for certain that the published text reads better as a poem than Tagore’s manuscript text? Scarcely so. Indeed, William Radice, one of Rabindranath’s foremost recent translators into English, is of the view – shared by many Tagore aficionados – that English Gitanjali – the landmark 1913 Macmillan book edited with an Introduction by W.B. Yeats – fails to do justice to a vast majority of the poems collected in the volume.

And one of the main reasons why Radice believes this happened is the rather cavalier fashion in which many of the poems’ layout has been fiddled with – and, unlike ln verse poems where line endings, metre and rhyme schemes determine the poem’s layout, in prose poems paragraphing plays a critical role. The very liberal paragraphing of many poems in the English Gitanjali, originally conceived as single-paragraph (or at most two- or three-paragraph) contemplations in understated, unadorned prose, has served to often significantly alter the poems’ tone, their complexion.

“The manuscript version”, Radice writes,“has a personal, immediate effect – precisely the kind of thing that one would write in a private notebook. The published version is much more incantatory, and has become a prayer for public use”. Indeed, writing in the year 2010, Radice tells us how “passaages from Gitanjali are used in Unitarian worship to this day”.

This mutation shows up even more starkly in the following example cited by Radice in which he reads the text of the English Gitanjali’s poem no 36 side by side with Rabindranath’s translation of the same poem. First, the poet’s own version:

This is my prayer to thee, my lord – strike, strike at the root of all poverty in my heart.Give me the strength to lightly bear my joys and sorrows. Give me the strength to make my love fruitful in service. Give me the strength never to disown the poor and bend my knees before insolent might. Give me the strength to raise my mind high above all daily trifles. And give me the strength to surrender my strength to thy will with love.

Let’s now turn to Yeats’s rendering of the poem for the printed book:

This is my prayer to thee, my lord – strike, strike at the root of penury in my heart.

Give me the strength lightly to bear my joys and sorrows.

Give me the strength to make my love fruitful in service.

Give me the strength to never disown the poor or bend my knees before insolent might.

Give me the strength to raise my mind high above daily trifles.

And give me the strength to surrender my strength to thy will with love.

In this instance, the emendations are even fewer than in the case of ‘Where the mind is…’ – and their value to the poem a matter largely of the taste of the individual reader. What is unmissable, however, is that the published text is more akin to a public religious invocation than to a quiet personal prayer reflecting an individual’s private religious-moral musings.

As Radice has emphasised, Rabindranath was of course a deeply religious person, but his religiosity was personal and meditative and he was at heart sceptical of institutional religion and its public rituals. (In that sense, it may indeed be more appropriate to think of Rabindranath as profoundly spiritual, rather than religious in the more commonly understood meaning of the word.)

Sadly, this is not what English Gitanjali conveys to most readers, especially to first-time readers of Rabindranath’s work. Rather, the image of the poet that leaps to the eye from the book’s pages is that of one ‘absorbed in God’ (Yeats’s words to poet Thomas Sturge Moore), an essentially mystic poet whose principal theme was communion with his god. Indeed, the first impressions that London’s cultural elites carried from their first exposure to Tagore’s poetry in the summer of 1912 – when the Gitanjali poems were read aloud to them in the painter William Rothenstein’s home by Yeats – were that here was a poet who was verily like “a powerful and gentle Christ” (Frances Cornford in letter to Rothenstein), an other-worldly, saintly man whose sangfroid and serenity belonged to a long-lost time which the modern-day world could only wistfully look back to.

No doubt such impressions were buttressed in no small measure by the poet’s appearance and demeanour as well: his fine, flowing beard, his aquiline nose and high forehead, the long, bright robes he was clothed in, his poise, the unhurried elegance of his manner and his very distinctive voice, at once deep and melodious. All in all, to his English audience, Rabindranath looked the perfect picture of the oriental sage of yore.

The often biblical tone of the English Gitanjali is also a function of the vocabulary and idiom that feature right across the book. And that tone is set right in the first stanza of the very first poem:

Thou hast made me endless, such is thy pleasure. This frail vessel thou emtiest again and again, and fillest it ever with fresh life. (Tagore’s manuscript reads:” ….with fresher life”, but ‘fresh life’ is a decided improvement.)

There’s no question that this biblicality – if we may use that expression – traces back in part to Rabindranath’s own translations, but, as Radice points out, it is significantly heightened by Yeats’s editorial interventions. The elaborate paragraphing of the poems that we noted above, Radice observes, breaks these poems up into ‘verses’ as in the Authorised Version of the English Bible. Besides, there’s the very important issue of the extensive changes that Yeats made to punctuation, particularly in the much more frequent use of the comma, which, together with the broken-down paragraphs, quite palpably affects the rhythmic energy of the poetry, slowing it down and giving it a somewhat self-conscious languor that impedes the tempo and modulates the cadence in a manner originally unintended by the poet. Here’s an illustration:

There is thy footstool and there rest thy feet where live the poorest and lowliest and lost. When I try to bow to thee my obeisance cannot reach down to the depth where thy feet rest among the poorest the lowliest and lost…(Tagore’s manuscript)

Here is thy footstool and there rest thy feet where live the poorest, the lowliest, and lost.

When I try to bow to thee, my obeisance cannot reach down to the depth where thy feet rest among the poorest, the lowliest, and lost…(English Gitanjali, poem no 10. Note the preponderance of pauses via commas here. Also, ‘Here’ replacing ‘There’ in the first line is an unnecessary alteration.)

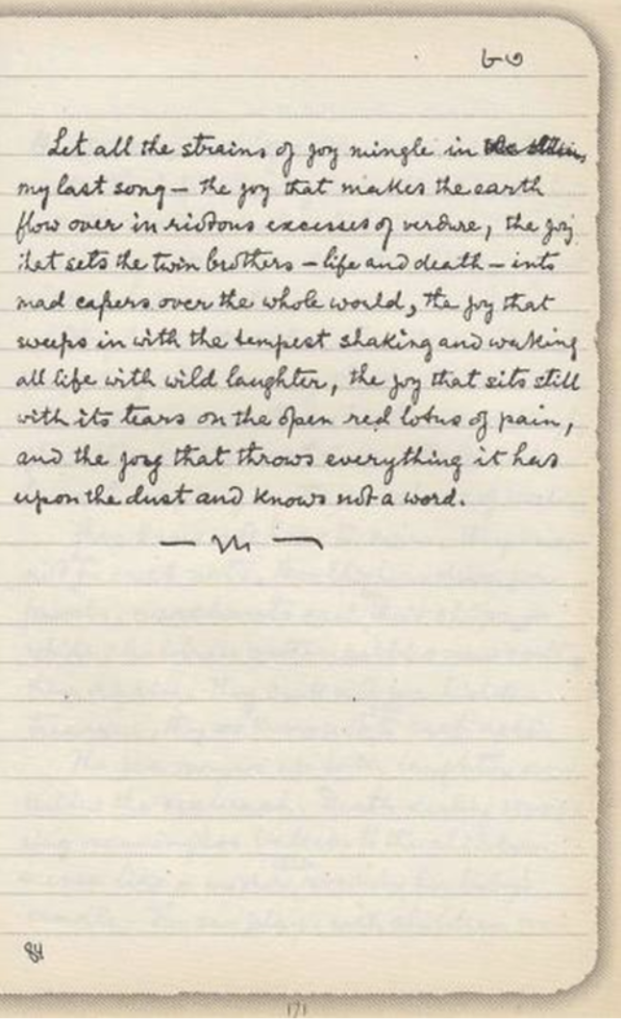

A page from Tagore’s manuscript of the English ‘Gitanjali’.

Radice has also suggested that Yeats’s frequent use of the comma and the semi-colon before ‘and’ (for example: “The morning time is past, and the noon.” or “The morning sea of silence broke into ripples of bird songs; and the flowers were all merry by the roadside; and the wealth of gold was scattered….”) in Gitanjali is a literary artifice common to the English Bible (“In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God…”) which sounds self-consciously archaic, ‘slows the pace and removes energy and turbulence’.

The distinct slant that Yeats’s editing imparted to Tagore’s translations was a product of Yeats’s very limited understanding of what had gone into making Tagore what he was. In Yeats’s estimation, Rabindranath was very nearly a contemplative hermit who represented to the Western world, where Yeats himself came from, “(a) whole people, a whole civilization, immeasurably strange to us”.

In other words, Tagore was “a symbol, a type, an icon”, a sublimely oriental personality who had evolved out of cultural impulses that were wholly unfamiliar, indeed alien to the West. This perspective was flawed on many counts, but most spectacularly in that it was completely blind to the very rich texture of the culture that Rabindranath grew out of, a texture in which Europe met and mingled with the East in great freedom.

Yeats’s celebrated Introduction to English Gitanjali didn’t see Tagore so much as a supremely-gifted individual working in a specific time and place towards poetic self-expression as the representative of a people that was characterised, in Ezra Pound’s words, by “this spirit of curious quiet”, by “this sense of a saner stillness come now to us in the midst of our clangour of mechanisms”.

Anyone who has read Tagore’s Gitanjali – or, for that matter, any single work of his – in its Bengali original does, however, know that a sense of exceptional spiritual calm was far from being the defining quality of his poetry. (And we need to remember that of the English Gitanjali’s 103 poems, only 53 were drawn from the Bengali Gitanjali, the rest having been gathered from several other collections of his poetry.)

Arguably, even the English Gitanjali in Rabindranath’s own translation – before Yeats got to mould it in his own mental image of the ‘Noble Orient’ – doesn’t pervasively exhibit “this sense of saner stillness” Pound talks so rapturously about.

Gitanjali also features exquisite love songs, like “I ask for a moment’s indulgence to sit by thy side” (poem no 5), as well as magnificent paeans to nature, like “I must launch out my boat. The languid hours pass by on the shore….”(no 21) or “This is my delight, thus to wait and watch at the wayside where shadow chases light….”(no 44).

Sadly, however, Yeats’s presentation of Gitanjali was to set the tone for the way in which Rabindranath was regarded in the West throughout most of his post-Gitanjali career. One reason, of course, was that while he won his Nobel as the author of (the English) Gitanjali – and that created such a sensation in its time – subsequent English translations of his poetry, quite many of them done by the poet himself, left a lot to be desired, no doubt because they were often rush jobs completed to meet publishers’ deadlines. So Tagore’s reputation in the West as a great poet rose and fell on his English Gitanjali – up until a new crop of capable and dedicated translators (viz., William Radice, Ketaki Kushari Dyson and a few others) emerged on the scene from the 1980s onwards.

Yet it cannot be said that Gitanjali – neither the Yeats presentation nor Tagore’s own manuscript of it, nor later versions done by Radice and others, nor even its original Bengali text – represents the best of Tagore the poet. The universe of Rabindranath’s poetry is infinitely richer and more varied than what Gitanjali offers a glimpse of, though William Radice would not necessarily have agreed with me on this. Semantically, structurally, in incredibly supple rhyme patterns and endlessly creative poetic idiom, and in its supreme musicality – not to speak of the staggering range of the contents he dealt with – Tagore’s poetry kept evolving till pretty much the last years, or even the last weeks, of his long life. So, though each of his poetry collections was sui generis, the world of Gitanjali, a book first published in 1910 (I am referring to the Bengali Gitanjali here), is necessarily defined by Tagore’s Weltanschaung and the stage of his moral-intellectual development at that point together with the poetic idiom (or idioms) he was most at home in then. Many themes and motifs and quite many skill-sets were to get added to his repertoire in later years, and these were to give his poetry a catholicity of temper, a breadth of vision and a technical virtuosity not yet attained in the Gitanjali years.

Anjan Basu can be reached at basuanjan52@gmail.com.

This article went live on August eighth, two thousand twenty five, at three minutes past eleven in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.