Three Stories From the Worlds of Bohra Muslims, Chettiars and Eurasians in Singapore

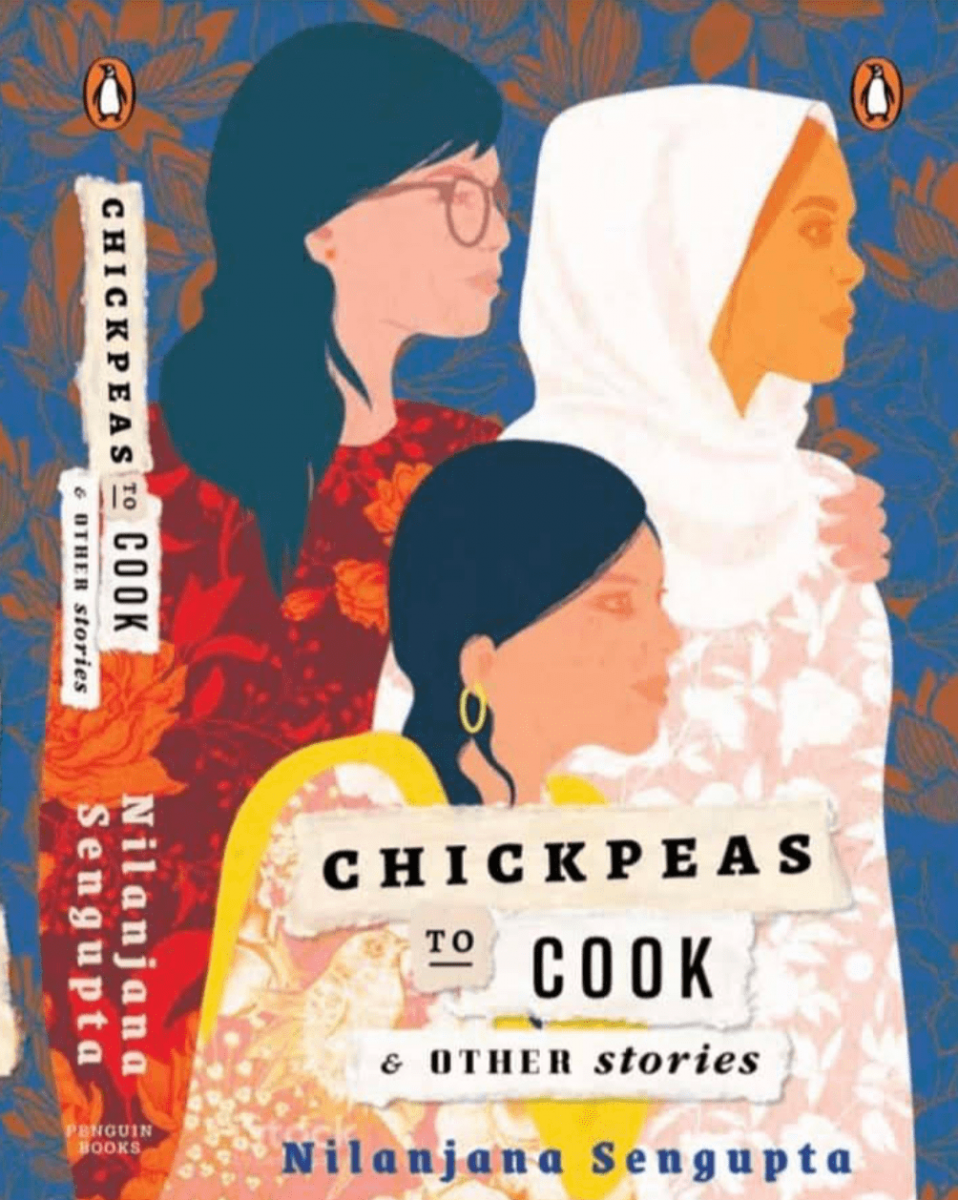

The following are three excerpts from Nilanjana Sengupta's Chickpeas to Cook, a book that looks at women of the smaller communities of Singapore. Some of these communities consist of only a few hundred families, where women find themselves caught at difficult intersections of faith, religion, family, community and country.

From Ablaze, the story on the Bohra Muslims

It was yet another evening. It had rained heavily the entire day. By then she was in junior college. They had moved to Chai Chee, the first of the Housing & Development Board apartment buildings of Singapore. She’d known she was late and so had sprinted up the staircase and rang the doorbell.

But the door hadn’t opened. She’d rung again, but it had remained shut. Aunt Susan from next door had come out to plead for her.

‘Come on, brother Hasan, have pity on the girl lah!’

'Chickpeas to Cook and Other Stories,' Nilanjana Sengupta, PRH SEA, 2023.

Finally, when Abba opened the door a couple of hours later, Sakinah was soaked through. The street outside had quietened down. Without a word she’d entered, sat down for her dinner. But then, at the sight of her, Amma had started crying and she’d known – this is it.

Abba had screamed, ‘Suk kam itni mori avi? (Why did you come so late?)’ and hit her hard across her face. He hit her again and again until Sakinah fell face forward into her food. And all the while, she could hear Amma cry, making the same soft, wailing sound that she always did, till Abba had taken his face close to Amma’s and jeered,

‘Soda water!’

‘That day, I thought to myself, what kind of a love is this? Amma was crying because she loved me so much, Abba was hitting me because he wanted me to be a good girl, and yet why didn’t their love make me happy?’

From New Beginnings, the story on the Eurasians

Will: I got my DNA test done (pulls out a paper from her pocket, shows it to Ruth)

Ruth: What! You of all people! I can’t believe it. Did you get patriciaed into it? Something to add to your precious family tree?

Will: No, no. Stop pulling Patricia into everything. That day in the wet market, when I went to buy chilli padi, you know, the day I wanted to make sambal belacan, remember, you told me to make it extra spicy with the grago from Portugal—

Ruth: (impatiently) Yes, yes, okay, the DNA test, you’re saying . . .

Will: Oh yes. There was this woman with a lot of makeup on her face, I remember because she was sweating a lot and her pink foundation was melting—

Ruth clicks her tongue again impatiently.

Will: Okay, okay, to cut a long story short, she asked me, ‘You speak like a Singaporean, but you don’t look like one. Where are you from?’

Ruth: But that’s nothing new. We’ve been asked that before. You yourself told me when Nana was asked . . .

Will: Oh yes, my dear father, he used to sit in the balcony of our Katong house every evening—reclining like this on his favourite planter’s chair, with his stengah balanced on his tummy . . .

Ruth: Yes, yes, I know, that gorgeous house with all its silver bought from Nassim & Co, its chaise lounges and lace antimacassars, a prie-dieu in every bedroom, and Nana’s Studebaker ....

Will: (smiling at Ruth approvingly, warming up) And so your Nana was sitting, when in walks a gentleman — in full silk suit and a hat, and Nana askes him as he usually did, all nice and polite, ‘Hey man, so what’s your poison?’ But the man, instead of answering, says, ‘I was noticing you in office today talking to the workers, so where are you really from?’

Will stops for a moment to look at Ruth to check for her reaction, then continues.

Will: My father, always cheeky! Too cheeky for his own good, if you ask me. Finally, couldn’t keep his job down, couldn’t keep his ang moh bosses happy. So, he looks the man up and down and says, ‘Where am I from! Bloody burger, I thought this was my land till you walked in!’

Ruth: Yes, exactly. Isn’t that exactly what you’ve told me always – that we’re the originals, the others are the imposters. So, what made you do the DNA?

From Brahman, the story on the Chettiars

They had landed at Kundrakudi with the sole purpose of finding Vishnupriya, all of twenty-six by then, a groom. After running through the list of promising bachelors in Singapore, Amma and Appa had failed to find someone within the community who could match up to their daughter’s qualifications. And so, Agasthya had walked into the picture – a software engineer, yet with his feet firmly grounded in Chettiar roots, nurtured by the wind and sun of their very own Kundrakudi.

That day it had been another day of Skanda Sasti celebrations. From the morning, it had been overcast. Under the gloomy sky, Vishnupriya had watched the preparations underway at the temple, the brass lamps that were lighted, the fire that rose in a searing orange flame, the pilasters with their vivid layers of bright colour that seemed to bear down on her just as they had done in her childhood, the yali’s fierce claws that seemed ready to tear away flesh. The courtyard outside was being prepared as a battlefield, iron stakes chiseled in the village foundry being driven in with powerful blows of a hammer.

Even beyond, morning gradually turned to a scorching, relentless afternoon. Agasthya and Vishnupriya had met away from all the commotion, on the banks of the Kundrakudi tank. By then it was early evening. There had been a brief downpour in the afternoon and the air had cooled down. The tank water rippled pale green, smooth as chiffon. Vishupriya wore a saree. Amma had braided red oleanders in her hair, little pinwheels from Murugan’s chariot.

When Agasthya walked in, she noticed a man lean for the height he carried, with quick eyes that not only noticed everything, but also seemed keen to engage with all that they saw, a moustache thicker than Appa’s over his upper lip.

Without much preamble, he had started talking about himself, the difficult life he and his mother had had after his father passed away young, how he got away from the village to study at Annamalai University. If anything, unlike her own usually tongue-tied self, Vishnupriya had noticed the rather portentous way of speaking he had, as if he thought every word he uttered would go down in history.

Yet today, when she thought of that evening, all she thought of was Shravanan. How was it possible that after all the miseries of his own childhood, Agasthya had so little empathy for his own son?

It was while they spoke that day in Kundrakudi that a young man whom Vishnupriya knew by sight had passed by. He had called out to Agasthya in a familiar way,

‘Annan, romba naalachu parthu, brother, long time since we saw you last!’

Agasthya had seemed inordinately pleased at being remembered. He’d waved at the man, and for a few seconds afterwards kept smiling to himself. Vishnupriya could imagine him going back home and telling his mother about the incident, both of them nodding in approval.

Difference number two, Vishnupriya had told herself. Unlike him, she hated being noticed and had always tried her best to blend in backstage.

§

In those initial years, Vishnupriya had thought Singapore and India would not remain separate for too long, Kundrakudi and that magical evening by the chiffon green waters would work as a bridge. Within a year she had sponsored Agasthya’s citizenship in Singapore and an extended permit to stay for Aathaa, her mother-in-law. They had moved to their new home in Tanah Merah.

Appa had been a regular visitor to their home then. Aathaa loved to hear him sing and her amiable father would happily sit on the divan, singing songs of Sundarar and Appar, one after the other till he was lost in their words, completely immersed in their beauty.

But then, as the marriage moved beyond its fifth anniversary – and Vishnupriya crossed the threshold of thirty – his visits became rare for on every visit, Aathaa would bring up the topic of Vishnupriya not conceiving a child.

‘Five years,’ she would sigh, ‘and yet there is no grandchild to play in our home. All she thinks of is office! Doesn’t she realise that as a wife, giving a child to her husband is her duty? Is this what this blasted country teaches her, only to work, work and work?’

By the end of the sixth year, Appa would come only once, on the day of Pongal. He would arrive bearing the gifts meant for a daughter’s home – the brass pots of jaggery and sugar cane and turmeric plant – and sit on the divan, looking mildly apologetic. Vishnupriya would watch Appa continue to laugh at what had been said, his eyes crinkling up because he knew if he stopped, the hurt would show.

It was Aathaa who had taught Vishnupriya to fast for Sasti in the hopes of a son. Every month, on the sixth night of the waxing moon, Vishnupriya would go to the Tank Road temple after office, having drunk nothing but water the entire day. In the evening after worship, she would eat a few slices of fruits. If for a few moments she would wonder what she was doing, standing in queue with the other women who had come to plead for boons, she would quickly brush the thought aside. For had not her parents always taught her that her first duty was towards her family? Singaporean or not, did not every Chettiar know that no sacrifice was too big when it came to the happiness of one’s parents?

It was a relief when Shravanan finally arrived – as dark-eyed as his father, as sensitive to his family’s wishes as his mother, as vulnerable in his need of their love. For a few years, their home in Tanah Merah overflowed with happiness. Amma and Appa would come every weekend bearing gifts and play with their grandson. Vishnupriya would watch indulgently as Amma and Aathaa cooked together in the kitchen, made the idiyappams and thosai that Shravanan loved, made fish poriyal but with very little chilli mixed into the curry powder. They would add tamarind juice to coax his taste buds, yellow ginger powder with its antiseptic qualities.

But as they say, whatever life gives, it takes away in equal measure. And so, with time, they made some unsavoury discoveries about Shravanan – that he did not do as well in school as they expected, that he did not seem to have the acumen for numbers that every Chettiar was supposed to be born with. Amma had wailed, she had known the scourge would someday return to haunt her again. Aathaa had fallen silent, sat in front of her altar as if turned to stone.

Agasthya had gradually distanced himself till he became one of those fathers whose only encounter with his son was a mutually disappointing one on the day of school results. And so, the years had passed till last evening, when Shravanan’s school principal called with the news that he was not able to cope with his STEM subjects, that he would have to repeat the final year of secondary school.

‘He’ll not accompany me to the temple today,’ Agasthya had burst out that morning. And even as Vishnupriya looked at him aghast, added, ‘I find it embarrassing! I have friends there from Kundrakudi, engineers who studied with me in university. They ask questions!’

‘We don’t go to the temple to meet your friends, Agasthya; we go there to meet God.’

Nilanjana Sengupta, an author based in Singapore. Her publications include, A Gentleman's Word: The Legacy of Subhas Chandra Bose in Southeast Asia (ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, 2012), The Female Voice of Myanmar: Khin Myo Chit to Aung San Suu Kyi (Cambridge University Press, 2015), My Country: Biography of M Bala Subramanion (World Scientific Press, 2016) and The Votive Pen: Writings on Edwin Thumboo (Penguin Random House, 2020).

This article went live on April twelfth, two thousand twenty three, at thirty-four minutes past five in the evening.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.