Alina Gufran’s debut novel, No Place to Call My Own, follows protagonist Sophia – the daughter of a Hindu Arya Samaji mother and Muslim father – as she navigates her life as struggling young writer in Mumbai. It explores her relationships, friendships, work and life, at a time when being from a religious minority in India is becoming more and more stifling.

Gufran spoke to The Wire about her decision to tell the story in the first person, how she responds to questions about whether it’s autobiographical, what it was like to be watching the 2020 communal violence in Northeast Delhi from a distance and then write about it, and more.

An edited transcript of the interview follows.

Although the story is told in the first person, it doesn’t seem like it’s blind to the protagonist Sophia’s flaws or messes, she’s not perfect.While it feels like she’s being truthful, the story would likely look different if told from a third person perspective. Do you think of her as an unreliable narrator?

I started developing the book from chapter 3 [set in Prague, while Sophia is in film school], that’s the chapter that came to me first, and I was very intrigued by the idea of putting a girl in a situation where she doesn’t end up doing the right thing. And also perhaps interrogating what the idea of the ‘right thing’ is, and how much of it is justified, what does that moral burden look like.

What was interesting to me in that particular chapter when I started writing the story was the gap between the reality of what was happening and what was going on in her head, and how she’s able to justify her actions as well. Of course it’s tinged with a lot of shame, but that dichotomy of a person being who they need to be and should be vs who they really are – and you’re especially able to experience it in the first person because you’re in her head constantly – was extremely interesting to me, because I do feel that literature is that one place which isn’t exactly the realm of politeness, and you can really get into the psyche of a character.

So yes, by and large I would call her an unreliable narrator.

A lot of the book is about her interiority. It’s about what she’s thinking, what she’s going through, the decisions she’s making. But at least to me reading it, it felt like as the book progressed, you saw external factors come in more and more. And then towards the end, they became equally important in some ways. Was that a progression that you planned, as a nod to the intensifying atmosphere in the country?

Yes, I think definitely a bit of both. Initially, the way the book starts, you’re primarily in her head and her concerns might even seem frivolous to somebody, right? And a lot of the concerns aren’t as [frivolous] well, they’re about being an artist, about making it in this artistic ecosystem that we live in, in a country where that isn’t that well supported.

And about having an abortion…

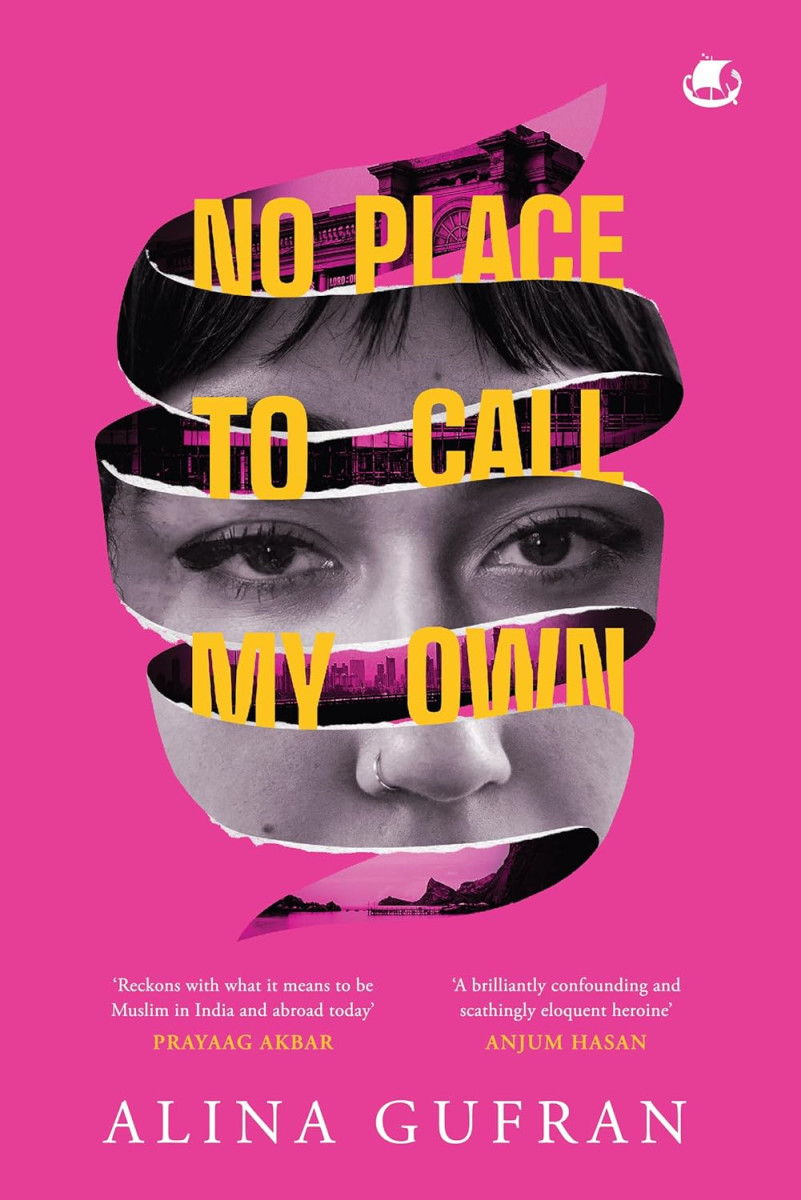

Alina Gufran

No Place to Call My Own

Westland, 2025

Yes. Also about being at the periphery of these very elite bourgeoisie circles she inhabits – and she is a part of it because her education has afforded her that, but she never really truly feels that she belongs in these circles because truly these circles are also concentrated in the hands of upper caste, upper class people. And maybe class isn’t that big a factor, but she’s always very aware of her identity, and also being the child of immigrants, etc.

But I think as the novel progresses, the reason the outside world becomes that much more pronounced is because she is having an awakening of some kind, whereas the doubts about her identity or the way she contends with the contradictions of who she is in the beginning feel internal, you soon realise that they’re not, that’s not entirely true, and perhaps that alienation from oneself is not just something you’re born with, it is something that’s repeated to you and becomes a refrain over the ages.

I think another interesting point for me to explore, which is also a little bit of a lived experience, is that we talk a lot about how 2014 was a turning point, and sure, in many ways it was. But I think for a lot of Muslims and other minorities living in the country, it’s tough to just pinpoint 2014, and that is also something that she starts contending with towards the second half of the novel.

Before I started reading I was looking at the contents, and each chapter is the name of a city. Going into the book I thought maybe spaces would play a strong role – like the city being a character along with her being a character. But that’s not really the case. What went behind thinking of each chapter as a different place?

I think one was a technical point of view for me, just from a craft perspective I wanted to see how she would change, adapt and the ways in which she wouldn’t be able to adapt, navigating all these different spaces. I think with children of immigrants – and not just children of immigrants, but also people who aren’t born into families that are granted societal approval right from the outset – code switching or having to adapt is kind of second nature, right? So for me that was always a very interesting and characteristic part of who she is.

So one was just that from a craft perspective, I was like, okay, I want to situate her in all these different places where she’s coming across situations and people that in part reflect her world back to her. Spaces where you think she would feel like she belongs the most are the spaces where she feels the most alienated, which is why in chapter two, when she’s in Beirut and she’s hanging out with a bunch of Arab filmmakers, essentially, she feels more of a kinship than she does, let’s say, back in Delhi, with her peers who are kind of assimilating into their parents’ businesses and such.

So when I do write, I tend to use a space as a backdrop, because I think there’s a lot in the environment the character can react to. So that’s one. And another is that there’s a certain urban alienation that’s hard to escape for all of us, and even for the character because the book is hyper contemporary, set in the now, it felt like I would be remiss to not couch it in the location that she’s present in.

You’ve been working in film for a while. What about this story felt to you like it’s a novel and not a film?

That’s a really nice question actually. I don’t know, I think when I first started writing the novel, it was at the heels of the pandemic, so the industry had shut down. I had lost a lot of my income sources. I was used to also screenwriting, but I was a writer for hire, I was constantly being commissioned.

There was something about this story where prose has always been a first love, it’s been a refuge from the world. And I was just compelled to write it. I think for the first time many of us we were all kind of taking stock of our lives, and for me the natural conduit for the story became prose. I actually haven’t even thought of it for the screen, and I think it’s primarily for selfish reasons because I just wanted complete control over the narrative.

Because the novel is written in the first person and also because you and Sophia do share some biographical details, like where you studied filmmaking, do people often assume that it’s autobiographical? How do you respond to that?

I think that’s been constant refrain since the beginning of the tour where everyone is intrigued and that is the primary concern – of whether it’s autobiographical or not. I understand the reason why people might need answers to something like that, but I also think it’s a bit of a moot point, because I don’t think it should necessarily matter.

I also think historically the writers that have inspired me, like Elena Ferrante or [Clarice} Lispector, or any of these sorts of authors in the canon, have always carried the burden of something having to be autobiographical for it to be qualified as literary fiction. Or Olivia Lang, I mean, I can go on, the examples are endless. And I don’t think people realise it, but I do think there’s a bit of a gendered approach to this. All fiction somewhere does come from a lived experience, you know, it’s coloured by your own bias as a writer. You’re kind of imprinting your DNA onto the world in so many ways. But I do believe that fiction writers don’t necessarily owe people whatever version of truth they might be looking for. s

So that’s one. But another is that I simply don’t think I possess that level of self-awareness, to write a character like me.

We were talking earlier about the ending of the book and how the external world is imprinting more and more on her life. What we see around then is the end of the anti-CAA protests and the communal violence in Northeast Delhi in early 2020, and then the start of the COVID lockdown. Now that’s a period that I think for a lot of us, maybe especially in this city, but nationally, was formative in some ways, but it also does feel like it was a long time ago. So much has happened in the last five years, and they do say this about pandemics and memory – that it sort of blurs the passing of years and also from the trauma you want to forget. What was it like writing about that period?

Actually it was a strange experience because the time I was writing those bits was very close to when this had happened. So in in some ways it was a very immediate response to what was happening.

For me, the second half of the novel feels intensely personal actually, because in a very visceral sense for me, it was a reaction. I was in Goa, I was very politically and culturally disconnected from what was happening in Delhi, even though my family is from here, I’ve spent some formative years here as a child. And there was a certain sense of helplessness, and the only tool that I really have is fiction. So it just felt I would be lying to myself and to the readers if I didn’t make that a part of the narrative.

I do know that Chapter 9 is a major turning point in the novel and it becomes quite visceral, but I thought it was important to document it somehow, especially in fiction. Stories do become a way of remembering and it wasn’t so much about the readers, but just for myself. It became a way mark that inflection point, because as much as I understand psychologically, it might be important to forget, I also think it’s important not to, and very recently, a fresh spate of violence in Nagpur… so I just thought it’s essential to have it down on paper.

What you’re saying now about you having written it then makes a lot of sense to me, because I read it, it did feel like things we felt in the moment and bringing that back to now, when it feels like it kind of almost happened to someone else.

It was a bit of a double-edged sword because I was, like I said, away from Delhi. There was no way really I could contribute to anything happening. But I was glued to online mediums and going into a fair bit of a spiral about what was really going on and I suppose when you know, ’80s have happened or early ’90s have happened, I’ve just been a child, but this was me witnessing it in a city I was born in, as an adult. So to not do anything about it just felt wrong.

You talked about this a little bit already but in a slightly different context, so I’m gonna ask it anyway. Are there some writers that you feel particularly influenced by, that you think have affected your work in certain ways?

Yes, of course. I think there’s a spate of the postmodernists. There’s Clarice Lispector, who was not really considered anything until much later, posthumously, which always seems to be the case, but I do think she’s a bit of a genius and rightfully deserves her space in the canon. There’s Mary Gaitskill, Shirley Jackson, then on this side of the world, I would say Avni Doshi’s recent book really inspired me. It was the first time that motherhood was really spelled out like that in the South Asian context.

Just before we close, is there something you’ve read recently or are reading now that you’re enjoying? And also maybe because of your past in film, something you watched as well.

I think two things actually. One was I just finished reading yesterday, The Anthropologists, [by Ayşegül Savaş] … I haven’t read her work before. I’m quite obsessed with the contemporary postmodern writers coming out of the Middle East, but they’re like second generation Americans. They have a very interesting lens. I thought it was extremely well written, I remember reading the blurb and it says something to the effect of ‘she is an author who just astoundingly knows,’ and I felt similarly. There’s something about her prose that has left an impression on me. I did feel that because of her background and where the story is set, and the kind of positionality of the characters, I thought there could be a bit of allusion – because I don’t actually believe in politics having to be the subject of something that, that’s the writer’s prerogative at the end of the day – but I thought there might be more of an allusion to the political times, but maybe the next one.

I think in terms of films, I think Anora was absolutely brilliant, because I felt like what Sean Baker started with Red Rocket, where he kind of alluded to that turning of the tide and that character being a metaphor for Trump, he just deepened into that craft and that those themes in this particular film.