The Elitist Beginnings of India’s First Foreign Policy Establishment

Most Indians have either never heard of the Indian Foreign Service (IFS) or have only the vaguest notion of what the service does. It does not have the name-recognition enjoyed by the Indian Administrative Service (IAS) or the Indian Police Service (IPS). Unlike earlier times, these days the IFS is not even the premier choice among those hundreds of thousands of candidates who annually knock at the doors of the UPSC to gain entry into India’s elite government services.

In order to bridge this gap, the distinguished journalist Kallol Bhattacherjee has sought to bring to public attention the persons who were first recruited to work as officers representing the newly independent nation that had never before had a professional cadre of diplomats to define and pursue its interests. Bhattacherjee refers to them as “Nehru’s first recruits” as the prime minister was the country’s external affairs minister till his passing away in 1964 and took a personal interest in those selected to join this new service. Nehru also dominated the shaping of foreign policy, influenced largely by his commitment to non-alignment, anti-colonialism and anti-imperialism, and Asian solidarity.

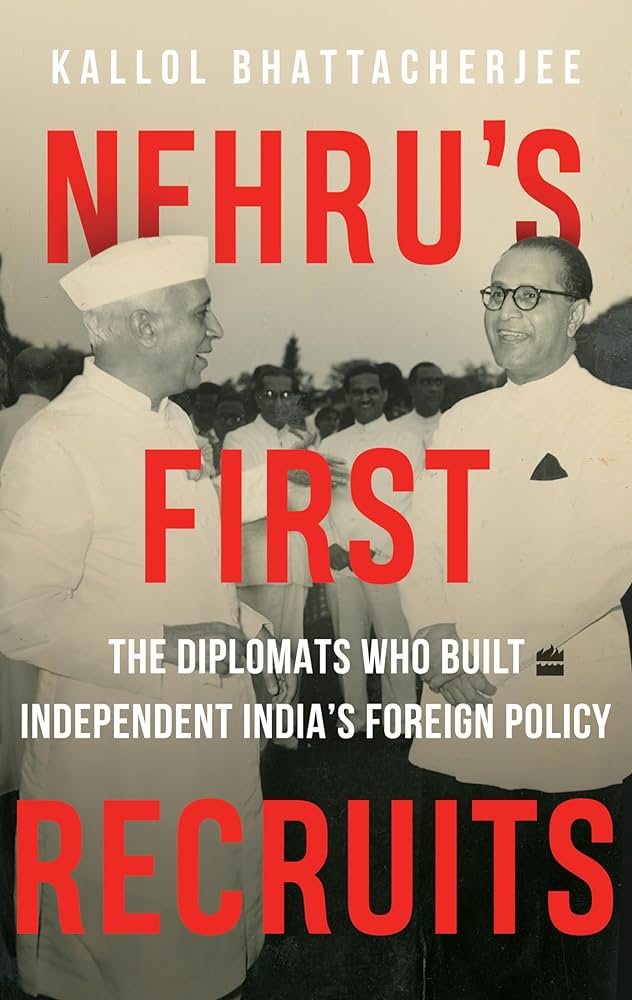

Kallol Bhattacherjee,

Nehru’s First Recruits: The Diplomats Who Built Independent India’s Foreign Policy.

HarperCollins India (2024)

The IFS was formally set up in 1947. The author points out that there was “something unique” about this new cadre in terms of the challenges it faced – the global binary shaped by the Cold War and independent India’s near-total absence of experience in handling international relations, defining a foreign policy to pursue these ties, and using professionally qualified officers to represent India in new and remotes locales.

The author has based his study of India’s first diplomats on the first History of Services published by the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) in 1958 that provided the names, some family details, language skills and postings of all those who were in the service in that year. The importance attached to foreign affairs is attested to by the fact that by 1958, India had 106 diplomatic missions and posts abroad – 40 embassies, 12 high commissions (embassies in Commonwealth countries), 12 legations, 10 commissions and 14 consulates.

The members of the fledging service were drawn from diverse backgrounds: officers from the ICS; young officers from the armed forces who had seen action in World War II; former members of Bose’s Indian National Army (INA); selected royal family members, usually from small principalities; a few with a media background, and some accomplished individuals who had come to the prime minister’s personal attention. In addition, a few joined the service from a “stenographers” background, rising through personal merit to senior diplomatic positions. From 1949 onwards, a small number of officers was directly recruited annually through the UPSC. The book discusses the careers of officers in the period 1947-58.

Not surprisingly, the ICS officers dominated the MEA: they provided foreign secretaries from their ranks till 1976, after which they were followed by two officers from a military background. The first officer from among the direct recruits to the new IFS cadre, Maharajkrishna Rasgotra, became foreign secretary only in 1982.

It is interesting to note that the influence of some of these early recruits continued well into the first decade of this century: two officers, Brajesh Mishra (1951 batch) and J.N. Dixit (popularly called “Mani” Dixit, of the 1957 batch) obtaine

Brajesh Mishra, India’s first national security advisor. Photo: X/@Indiandiplomats

d post-retirement appointments as national security advisers under former prime ministers Atal Bihari Vajpayee and Manmohan Singh, respectively, while Natwar Singh (1953 batch) had joined politics in 1984 and was briefly external affairs minister in the Manmohan Singh government.

Bhattacherjee’s approach is to devote a chapter each to one or two officers who joined the service from different backgrounds, and provide some personal details and a brief account of their career, usually supported by a thumbnail account of the political context in which they worked.

He managed to get several interviews with well-known public figures such as Natwar Singh and Brajesh Mishra. He also obtained substantial information from family members of less known officers such as Dileep Kamtekar (1952 batch), S.J. Wilfred (from a stenographers’ background), K.M. Kannampilly (political activist from Kerala), Cyril John Stracey (INA background), Leilamani Naidu (daughter of Sarojini Naidu; joined the IFS in September 1948, becoming the first lady officer in the service), and MRA Baig (from military and INA background, former private secretary to Jinnah; India’s second chief of protocol).

Superficial content

Though Bhattacherjee’s is a pioneering work, most of us would ask for more, far beyond what the book provides. While the political context abroad in which different officers worked is interesting, at no point do they come alive – we know almost nothing about their personalities, their world-view, and in what ways they contributed to building India’s foreign policy – as the sub-title promises. The diplomats themselves remain cardboard cut-outs. The book would have emerged as a much more substantial a work if the author had interviewed younger IFS officers who had served with these first diplomats (as he has done in one or two instances).

For instance, I was very pleased to see the name of Roy Axel-Khan in the list of officers from came from a stenographers’ background. He had joined the Indian high commission in London as a clerk in 1948. At some stage, he was promoted into the IFS and served in Tehran and Baghdad, before becoming a trade commissioner in Kuwait. After the sheikhdom’s independence, he was India’s third ambassador, and the first ambassador I worked under, when I came to Kuwait as the third secretary (officer-trainee). Axel-Khan was a remarkably urbane and sophisticated envoy, who was, inter alia, deeply committed to my training.

The shortcomings in the book due to the choice of sources are aggravated by the author’s totally uncritical approach – he takes at face value everything told to him by first-hand and second-hand sources and does not ask difficult questions of his interlocutors.

He does not question whether there could have been alternative approaches to setting up the fledging foreign service. Nor does he discuss the implications of shaping the foreign policy of the new nation by a powerful cabal of ICS officers who, in most instances, had no experience of foreign affairs and whose formative period had been spent in serving the Raj in districts and provinces in British India. Since none of them had participated in the freedom struggle, how could they be expected to reflect the values and interests of the new national order?

C.S. Jha, India's foreign secretary (1965-1967). Photo: X/@Indiandiplomats

Again, he fails to point out the culture of arrogance and entitlement that defined the persona of several early recruits, with many of them hardly living up to the standards of intellectual rigour and personal probity expected of them, a bane that has possibly exacerbated in recent years. Flowing from this, it is surprising that the author does not discuss the issue of reservations in the early years of the service. Did several officers not nurture and exhibit serious caste prejudices so that officers from reserved categories often felt excluded from the ministry’s mainstream and were frequently denied the more attractive appointments the service offered?

This leads to further questions: given the strong western cultural orientation that shaped the ICS and early direct recruits, did this not impart a strong bias in favour of postings in Western capitals, consolidated further by early training at Oxford, Cambridge and London? Despite the avowed national policies of non-alignment (and now affiliation with the “Global South”), such a hankering for postings in Europe and the US persists among foreign service officers to this day and has led to a consistent neglect of large parts of Asia, West Asia, Africa and Latin America in South Block.

We must also ask: eight decades since the service was set up, why does the IFS still reject area and subject specialisation? Is this because such specialisation would jeopardise the chances for western postings that most officers still desperately seek?

Final questions

Given that the early recruits cast a long shadow of the functioning and ethos of the service, it is important to raise two larger issues.

Firstly, why has South Block never shaped a long-term vision and a supporting strategy to define and pursue India’s national interests? Bhattacherjee says that the agenda that the early diplomats were expected to implement “was not very complex”; these diplomats “were expected to have a perspective of their own”, have an “innovative approach”, and needed to have “an opinion that would serve the Indian position”. What was the goal of foreign policy? The author simply says that this could be culled from Nehru’s public statements and it was “to serve the people of India in their hour of distress”.

Frankly, such platitudes are not conducive to serious foreign policy-making. The absence of a coherent and substantial long-term approach to India’s crucial interests remains a serious shortcoming even today. In 1992, a visiting American observer, after long conversations with members of India’s security establishment, had concluded that decision-making in India on security issues was reactive, defensive, short-term and ad hoc. Over three decades later, can anyone deny that this is still the case today?

Secondly, what values have the first recruits left the service? The author asserts that the service has been “fiercely protective” of the political leadership. This contention is at best questionable. But what is not deniable is that senior officers have generally been “fiercely protective” of wrong-doers who were close to them: on several occasions, the misdeeds of erring officers were whitewashed and promotions to the top echelons of the service given to obviously underserving officers. This had a deleterious impact on service morale that continues to this day.

Looking back, there can be little doubt that the IFS that emerged at independence reflected what a scholar quoted in the book has called “the concealment of continuity”, ie, the Indian state generally replaced the colonial state, with the Indian elite merely replacing the British ruling elite, while retaining the earlier political, economic and social power structure intact. Real change in the foreign service emerged only in the 1960s when a new generation of officers, nurtured entirely in the post-Independence era, began to join the service. But several pernicious aspects of the old order have not been shrugged off and remain a bane today.

Talmiz Ahmad belonged to the 1974 batch of the IFS and briefly had a worm’s eye-view of some of ‘Nehru’s First Recruits’.

This article went live on August sixth, two thousand twenty four, at twenty-two minutes past twelve at noon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.