The Legacy of Sheikh Abdullah Amidst Shifting Narratives in Kashmir

In the aftermath of Sheikh Abdullah’s pivotal accord with Indira Gandhi in 1975, a poignant cartoon appeared in an English daily that depicted the transformation of Sheikh Abdullah’s image from a formidable ‘Sher-e-Kashmir’, to a seemingly toothless lion, stripped of its dentures. Against the backdrop of Indira Gandhi wielding a whip, the cartoon's caption read: ‘He will roar but cannot bite.’

By the end of 1974, Abdullah's revolutionary fervor had waned, replaced by a treacherous – or, as some would say, pragmatic – acceptance of the position of chief minister of Jammu and Kashmir within the Indian union. It was a momentous decision for which he has earned revulsion from Kashmiris to this day, yet at the same time, he appeared to be an inevitable choice.

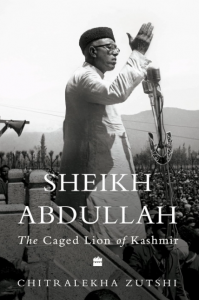

The second biography in the Indian Lives series, Sheikh Abdullah: The Caged Lion of Kashmir by Chitralekha Zutshi, edited by Ramachandra Guha, successfully captures the essence of its subject and presents a much needed exploration of a man who was both deeply admired and often derided. A guide and a harbinger of freedom to some but at the same time a traitor, a demagogue and an opportunist to others.

Sheikh Abdullah: The Caged Lion of Kashmir by Chitralekha Zutshi (Fourth Estate India, December 2023)

In contemporary Kashmir, inquiring about Sheikh Abdullah often yields acerbic responses with many condemning him for selling Kashmir down the drain in 1975. Zutshi delves into this problem meticulously and reaches an interesting conclusion.

Kashmiris born prior to 1947 continue to revere Abdullah as a pious, peerless individual. However, the generation born after 1947 – who came of age when he was in prison and were young adults at the time of 1975 Kashmir Accord – are particularly embittered by what they see as a betrayal of their political dreams; dreams that he had himself fostered.

The first biography of the series is about Ashoka, authored by Patrick Ollivelle.

Jawaharlal Nehru’s unwavering backing of Abdullah in his struggle against the Dogra Raj paid off in the form of the state acceding to the Indian union in 1947. It was evident that Nehru, with his distinct motivations, strategically nurtured Abdullah as a counterbalance to Jinnah and his two-nation theory. Abdullah did not need Nehru as much as Nehru needed him at this point of time in Kashmir’s history. However, when Abdullah began to outgrow his assigned role in 1953, he was decisively curtailed and put under arrest.

Prison punctuated his political life multiple times. He would spend a total of 16 years, six months and 22 days in jail as a prisoner either of princely Dogra state before 1947 or the J&K state within Independent India that followed it.

1953 was a pivotal moment in the association between Kashmir and India, altering its dynamics forever. The escalating Praja Parishad agitation in Jammu, spearheaded by Balraj Madhok, strategically aligned itself with the Jan Sangh, exerting significant pressure on Nehru, resulting in the dismissal of Abdullah in 1953. Jammu Hindus were acutely unhappy with the economic policies of the National Conference, particularly the passing of the Big Landed Estates Abolition Act in October 1950. According to this Act, the maximum amount of land that a landlord could hold was 182 kanals (22.75 acres) and transfer the rest of the land to the tenants, who had until that point worked as serfs on the land. The Praja Parishad felt that this was against the interests of the landlords of Jammu.

The movement demanded ‘Ek Vidhan, Ek Pradhan, Ek Nishan’ (One Constitution, One Prime Minister, One Flag), precisely to undo these reforms. For Sheikh, India meant Nehru, and this is where he erred. His friend, on whose advice he had once converted the Muslim Conference into the National Conference in 1939 and earned the wrath of his fellow companions, was accusing him of being communal and approved of his arrest in 1953.

Jawaharlal Nehru in conversation with Sheikh Mohd. Abdullah in the Constituent Assembly. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Life in prison and sacred spaces

Abdullah’s enduring popularity as the most significant leader of Kashmir through a large part of the 20th century, according to Zutshi, is best understood through the lens of two themes that defined his political career: prison and sacred spaces.

To illustrate this, two crucial instances from his political career are paramount to understand. In 1953, Abdullah’s administration faced criticism for severe corruption and other maladies. His plummeting popularity was instantly restored as soon as he was dismissed in 1953 and made a political prisoner again, allowing him to reprise his role as a revolutionary leader of the movement of Kashmiri self-determination. In 1975, after the accord with Indira Gandhi, Abdullah’s popularity in Kashmir took a severe beating. In an attempt to salvage his image, he initiated the construction of Hazratbal shrine, aiming to turn around the public opinion but failed to do so substantially.

He would not allow Kashmir to be merged into and fall to the tyranny of the postcolonial state after delivering it from the authoritarianism of princely rule. And yet in one of the central contradictions of his political career, at certain times when he was in power, he himself became the postcolonial state’s most trusted agent and the repressor of his own people’s rights. His image as a Muslim leader in Kashmir was one that he would carefully cultivate and maintain even at the cost of alienating people from Jammu and Ladakh provinces of the state. Ideally, he wanted to be both a Muslim leader as well as a secular, nationalist one, but succeeded in being neither.

In the contemporary Kashmiri psyche, Abdullah’s image is less that of a liberator who freed his people from the clutches of feudalism and Dogra rule, endowing them with a sense of dignity. Instead, he is often perceived as a figure who veered away from the very cause of Kashmiri nationalism that he had meticulously crafted and ardently fought for. As his life drew to a close, the spectre of ‘Kashmiri nationalism’ haunted him. He was called a Frankenstien who created the monster of ‘Kashmiri nationalism’ and now had to pay the ultimate price.

Zutshi’s biography brings to the table an array of arguments that act as a counterbalance to this dominant narrative. The watershed moment of losing East Pakistan in the 1971 India-Pakistan war played a pivotal role in shaking Abdullah’s belief in Pakistan being a potent player in the Kashmir dispute. He lamented that he could not stand idly by witnessing the gradual decline of his beloved Kashmir, plagued by corruption, familial separations across borders, inflation, and unemployment among the educated.

Motivated by a profound desire to rectify these issues, he made a strategic return to power with the ambitious vision of forging a New Kashmir. The Kashmiri cartoonist, Bashir Ahmad Bashir, captured the feelings of the people at this time. In one of the cartoons, he showed Abdullah striding towards the chair of the chief minister while a grave in the background marked ‘Liberation Front’ cries out, ‘Meri Kahani bhoolne wale, tera jahan aabaad rahe’ (Oh you, who forget my story, may your world prosper). He died a sad, broken man, crushed under the weight of his unfulfilled promises to the Kashmiri people. This biography by Zutshi is as much a biography of this one towering man as it is of the entire generation of leaders who shaped the destiny of Jammu and Kashmir forever.

Saleem Rashid Shah is a book critic and an independent writer based in Kashmir.

This article went live on January thirteenth, two thousand twenty four, at sixteen minutes past four in the afternoon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.