The Legal Path to Being Arrested for Merely Loving

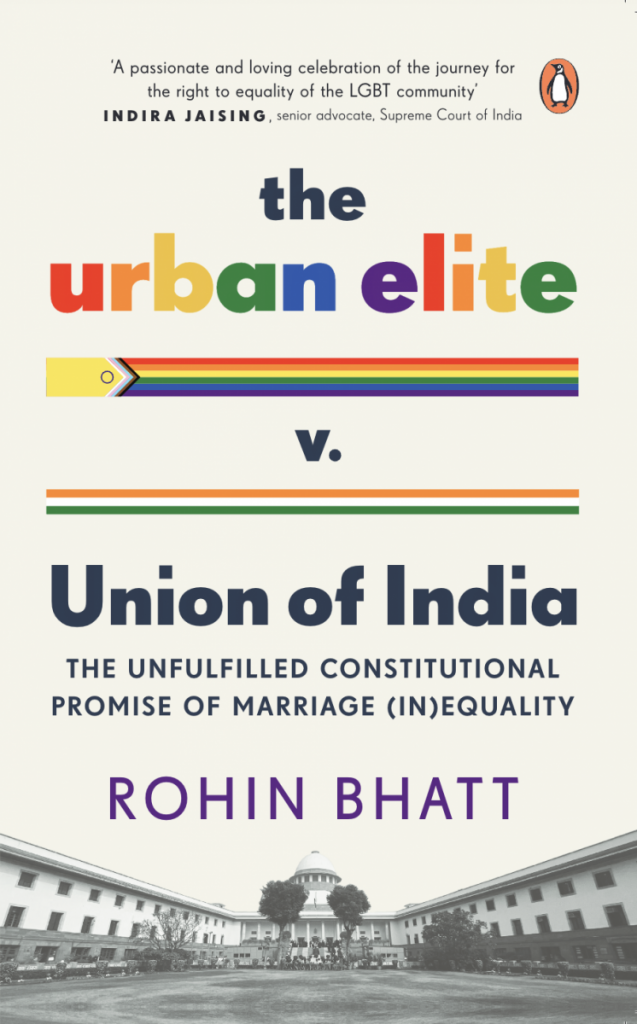

The following is an excerpt from Rohin Bhatt's book The Urban Elite v. Union of India: The Unfulfilled Constitutional Promise of Marriage (In)Equality, published by Penguin.

It was a cold December night in 2017. As a nineteen-year-old, I was enthralled by the promise of Grindr, a gay dating app that I had just stumbled upon. Until I discovered Grindr, the world was a lonely place. I was a nerdy queer child who was bullied and would often look up the word ‘homosexual’ in the yellowed pages of my mother’s copy of the Oxford English Dictionary.

Eventually, I ended up going on one of the first dates with a young doctor. After warming ourselves with several cups of coffee on a chilly winter night in Ahmedabad, we were driving around the city. I do not remember what we were talking animatedly about, but one thing was certain – there was sexual tension, the kind that makes your heart beat so loud that the other person can almost hear it. I think they felt it too, for they leaned in and kissed me at a traffic signal. I blushed. Immediately, there was the sound of a police baton on the window.

*thud* *thud* *thud*

I froze.

'The Urban Elite v. Union of India: The Unfulfilled Constitutional Promise of Marriage (In)Equality', Rohin Bhatt, Penguin, 2024.

A policeman barked at us in Gujarati, ‘Bahar nikdo gaadi ma thi’ (Get out of the car.) He told us he would call our parents (although we were both adults) and that he was, amongst other things, arresting us under Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code. The reason? I was kissing another man.

Having gone through a fair bit of law school by then, I knew that homosexuality was a crime in India, and that I was an unconvicted felon. A conviction under Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC), which criminalized homosexuality, carried a term of life imprisonment, or imprisonment upto ten years and also a fine. Not to mention the consequences of a criminal trial, and the social and moral censure that would undoubtedly follow. I had no idea what to do. I froze. In that moment, my mind raced. I was not out to my parents. To my friends. To the world at large. Hell, if I am being honest, I was not out to myself.

What was going to happen? Would I be thrown out of the house? Would the world accept me for who I am? My mind was racing, and my heart was beating at a gazillion beats per second. After much cajoling, and the person I was with paying a hefty bribe (he refused to let me chip in), the policeman let us go. As I write about that incident today, my hands quiver and my throat goes dry. What happened then was part of the reason I did not come out well until I knew that I had perhaps ‘made up’ to the world at large for my sexuality. Admission into a master’s degree at Harvard Medical School sure ought to compensate for my queerness, right? What I lacked in supposed normativity when it came to sexuality, I ‘fixed’ by checking another box. I did not have the guts to come out to anyone in person except for my sister and a friend. I mostly did it over text messages. Everyone else came to know about it through an Instagram post on 28 March 2021, a few weeks after I got into Harvard.

As a queer person who is a lawyer, this book is animated by lucid rage at having almost been arrested for merely loving, and an abiding disgruntlement with the Supreme Court for its judgment in Suresh Kumar Koushal and Another v. Naz Foundation & Ors (2013) which recriminalized homosexuality after the Delhi High Court, in Naz Foundation v. Govt of NCT of Delhi (2009), had decriminalized it, and now in Supriyo Chakraborty v. Union of India in October 2023, where the Supreme Court has held that there is no fundamental right to marry, and that the right to marry is a statutory right which queer persons do not have. For me, as it is for other queer persons, the meandering legal path that the queer movement takes, despite all of its internal fractures and divisions, is personal, and the personal is legal. This lattice of this book will mesh the personal with the legal. While it is primarily about the marriage equality litigation, it will intertwine with it my lived experiences of queer joy and euphoria, of homophobia, and of the way I have found myself in the midst of the queer rights movement in India.

You do not have to be queer or a lawyer to read this book. But it is about queerness and the law. I want to talk about the experience of the law through a lens of queerness, as someone who has been a part of it, not just as a lawyer but also as an activist. This book also maps my short journey as a lawyer. Usually, one does not write such a book until one is either bald and wrinkled, or dying. Well, perhaps this is what it means to be queer. You break norms. You do not adhere to the rules and boundaries which are set for you. Deviants. That is what we were called for the longest of times. Perhaps it is time to reclaim the word.

The book is not a legal commentary, nor is it a hyper-technical book on the law. It is not going to be too legalistic but is aimed at breaking down complex court-speak in a way that is accessible to the people who may have not studied the law.

A lot of people were following the marriage equality case which came to be called Supriyo Chakraborty v. Union of India (after the lead petition), along with connected matters where nearly fifty non-heterosexual couples were asking for the right to marry. Since this was one of the first cases that had garnered wide public interest and was being live-streamed, I was asked a number of questions: Was approaching the Supreme Court when the cases were pending before the high court the right move? Why were we seeking a declaration?

What is a declaration? What does a mandamus mean? What is constitutional comity? What is the difference between reading down and reading up a provision? But perhaps, the most persistent question was: Will we win? Fascinatingly, whenever the last question was asked, ‘we’ was used not just by queer people but also by allies. Since the live-streaming had taken the case into living rooms, a lot of people, gay or straight, felt as if they had a personal stake in it.

Rohin Bhatt is a Supreme Court advocate and has a Master of Bioethics from the Harvard Medical School. He is a member of the Lawyer's Collective and co-founder of the Indian Bioethics Project.

This article went live on September twenty-seventh, two thousand twenty four, at zero minutes past eight in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.