Exploring State Repression and Its Psychological Aftermath

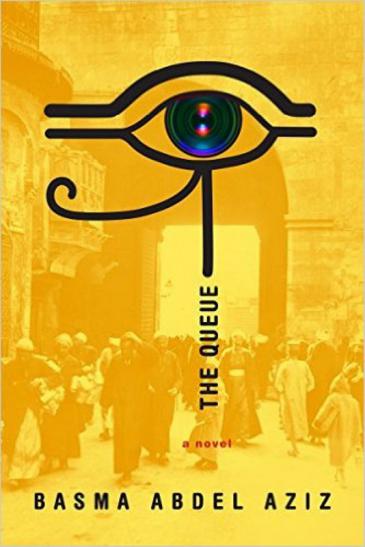

Through The Queue, a dystopian novel, Basma Abdel Aziz provides an incisive look into the functioning of dictatorships.

People line up at a polling station as they wait to cast their votes during parliamentary elections in Cairo November 28. Credit: Reuters/Amr Abdallah Dalsh/ File Photo

Basma Abdel Aziz wrote The Queue in 2012. Translated by Elisabeth Jaquette, it appeared in English in May last year.

Set in an unnamed country, the novel revolves around the Gate and, by extension, the Queue, with the latter being the main focus of the novel. The Gate – where the authority resides – has closed down for an indefinite period of time. Nevertheless, the citizens still require permission from the Gate for everything, from the simplest to the most complicated activities.

This clampdown and bureaucratic maze have come on the heels of a failed popular uprising called the Disgraceful Events – which has divided the citizens over its merits. The novel is as much an inquiry into state repression both before and after the Egyptian Revolution as much as an attempt to examine the psychological implications of a centrally constructed structure such as the Queue. The citizens stand in the Queue and it becomes “like a magnet… [it] drew people toward it, then held them captive as individuals and in their little groups... it stripped them of everything, even the sense that their previous lives had been stolen from them.”

In the 2012 biopic of Hannah Arendt, the character Arendt tells her students that “the entire concentration camp system was designed to convince the prisoners they were unnecessary”. There is no real point in comparing Adolf Hitler's concentration camps to anything else, but Arendt’s genius lay in giving us a vocabulary to discuss many such totalitarian systems. They ring true for The Queue as well. The Queue has been designed purposefully, so that the countless people queuing up outside it for equally countless – and ridiculous – reasons are rendered jobless and worthless. In the concentration camps, the psychology of terror was at play, in The Queue the terror is limited and mixed with uncertainty and optimism, leading primarily to manipulation.

The people in Aziz's dystopian nation are also in a camp, but they are hardly aware of it, because they cannot see any physical or visible walls around them they feel free. They are also unaware that the Gate is building walls around them, walls which are invisible yet – or perhaps hence – deadlier. Come to think of it, the idea behind 'concentrating' a population to monitor and eventually eliminate is also the point of the Queue, with the exception that it does not seek to eliminate – or at least not yet, although it is easy to imagine that it could do so. People from within the Queue who have uttered words of frustration and dissent against the Gate have disappeared. Although the number is not high, the people in the Queue notice these disappearances. Moreover, they have returned, presumably without any physical damage but with a mental trauma which persists.

Take the case of Amani – whose is the only case we are given – who, after a series of events, is detained and dumped in a dark hollow, where “she heard no voices, her hands felt no walls, no columns, no bars.” Amani is detained, but she has no idea where and to her it all feels like nothingness – if one can call that feeling. The emptiness outside mirrors the emptiness inside Amani and her mood swings from rebellious denouncements to pleading for forgiveness. It doesn't matter, though, because in that void she is alone and nobody is listening.

Amani is denied simple needs. Needs we are never even aware of – the need to touch, the need to smell something, anything and the need to talk with the assurance that someone would listen. There's no physical torture in Amani's case, but she is put in a situation where she is not sure of anything and she would prefer physical torture to this trauma. Because torture would mean someone touching her and touch, after a point, is what she desires, irrespective of how it comes. This chapter, titled 'Nothingness', is suffocating for the reader, who suffers along with Amani.

Otherwise, though, the reader remains alienated from the characters. It is difficult to feel any real pity for the character of Yehya, for example, who took part in the Disgraceful Events and whose body has become "a map of the battle." A bullet is lodged inside his body and tragically, since the Gate denies having fired any bullets on its citizens, Yehya is the only one who can prove otherwise. That, however, does not change the reader's emotions – Yehya remains someone who took part in the events and is suffering for it, but the reader – this reader anyway – does not really wish that the bullet be finally removed and Yehya be saved.

There is a similar ambiguity with Amani and the chapter before 'Nothingness' when she is in the military hospital. The chapter is supposed to be a thrilling point in the novel, a push to the narrative, but it manages to retain the same pace as the rest of the novel, which is to say drab. Not even the brief chase within it alters this.

Eventually this drabness makes the reader care less about the characters and the plot and more about the themes that Aziz is trying to present. It is astonishing how a novel that doesn't really impress prose-wise can provide a number of themes to mull upon. It is almost as if Aziz wanted the reader to be disinterested in the prose and plot because she wanted the themes to emerge and stand out rather than the story itself.

If that is the case, it is unfortunate, because the story Aziz narrates is the story of a real, troubled and silenced Egypt that woke up and that story is vital. Take, for example, the military hospital Zephyr: the surrealism starts from the name, for the hospital is anything but a breath of fresh air. In fact, it is an enclosed space with rooms which are crammed with files and presumably secret passages that wind down to more rooms crammed with files. The hospital in Egypt is an institution that, during the time of the despotic Hosni Mubarak regime, failed to function.

Alaa Al Aswamy, an Egyptian writer, writes extensively about this in his On the State of Egypt, appropriately sub-titled 'What Made the Revolution Inevitable.' The state of medical services in Egypt was, without a doubt, one of those reasons why it became inevitable. In one of the columns, 'Who is Killing the Poor in Egypt?' he relates the story of Nashwa, the sister-in-law of a famous Egyptian journalist. She is involved in a traffic accident and taken to a government hospital where she is “dumped into a place... without any first aid or treatment and without any doctor examining her.” After much delay on the part of the doctors and shouting and threatening on the part of the journalist, Nashwa is treated, scanned and then moved to a private hospital. She is saved but Nora Hasem Mohamed, an ordinary woman from the lower rungs of the society who falls gravely ill one day, is not.

Aswamy mixes Nora's story with that of the Egyptian football team's match with Algeria, highly publicised and attended by the nation's health minister – which is the point. While Nora is transported from one hospital to another, ignored and made to wait, the health minister worries about Egypt scoring a last minute goal. While Nora dies of neglect, the health minister, along with Mubarak and his sons celebrate that last minute goal. “Congratulations to Egypt for reaching the World Cup and may God have mercy on the soul of Mrs. Nora Hashem Mohamed,” Aswamy concludes.

The hospitals in The Queue are equally depressing. Tarek, the doctor handling Yehya's treatment – or the absence of it – is a conflicted figure who is and has always been on the right side of the law. He is initially very agitated that he has to handle the case of Yehya, someone who is suspected of taking part in the Disgraceful Events. He is miserable about the whole prospect and puts off Yehya every time the young sales executive comes limping in for a progress report on his file.

The whole cycle of indifference and bureaucracy described within The Queue reminded me of the comic yet poignant pages in Nihad Sirees's The Silence and the Roar – when a doctor asks the protagonist, a writer, to give him a word “for what's going on here.” The scene is played out in a hospital where scores of patients have been admitted of which many have died in a march glorifying the despotic Leader. They all have died in 'national interest' and for the love of the Leader which leaves the doctor depressed. All he needs is a word and the writer gives it to him: “surrealism.”

In The Queue though, even the surreal is drab and Tarek the doctor comes off as a cardboard character with whom the reader does not develop any kind of a relationship. That again is problematic because these are the protagonists of the novel and their actions need to evoke emotions within the reader. Admittedly, that is not absolutely necessary in each and every novel, but the actions of the protagonists in The Queue and their development through those actions is prominent. But it feels like the development comes without any kind of a catalyst and is thus unjustified. So when Tarek finally comes around to doing something about the whole business, we are not impressed and it feels too little, too late anyway. Which it is.

Yehya, Tarek, Amani and the scores of others in the novel all had the potential of developing into strong characters who are suffering and have no way of doing anything about it. But we are only provided with a hawk's eye view of their stories and are instead left with a number of themes to discuss.

The Queue is not a bad novel, but it is disappointing due to its potential to be a tale of the psychological control a state can wield over its population without the latter having any idea about it. Sirees's novel, which was written in 2004 and translated in 2013, manages to underscore that point better and in more effective terms than The Queue. Curiously, even Sirees places his protagonist in an unnamed country, though a lot of people have placed him in Syria. Perhaps that is right, because in an afterword, Sirees writes about the roar of “artillery, tanks and fighter jets” that have “already opened fire on Syrian cities.” It makes it all the more easier to place the protagonist in Syria, rather than say North Korea, a nation that seems closer to the unnamed country of Sirees's imagination in its absurdity.

Do these writers place their fiction in unnamed nations to defy the Western idea that novels coming out of the Middle East represent an insight into the “war-torn” and “troubled” part of the world? Can this structure be interpreted as a way to protest against the perception of Middle Eastern fiction being a personal experience and an exotic journey into conflict, all the while forgetting the aesthetics of that fiction? Perhaps a case for this is presented by Ina Kosova in her post on Khaled Khalifa's In Praise of Hatred on the blog Arabic Literature. But perhaps Sirees and Aziz use, in the words of Mia Couto, “untruth” to “fight the cause of truth” thus revealing a “lie that doesn't lie.”

In any case the lie they present to us is a terrifyingly alarming one, one that, in The Queue, is capable of rendering necessary people unnecessary.

Atharva Pandit is a student, currently pursuing a BA in politics at Ramnarain Ruia College, Mumbai.

This article went live on February eleventh, two thousand seventeen, at eleven minutes past four in the afternoon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.