Ankur Bisen’s book Wasted: The Messy Story of Sanitation in India, A Manifesto for Change, written lucidly and packed with information (sans tables and charts), makes for a great read for all concerned global citizens. This book could not have been more propitiously timed than at this hour when global society is battling various environmental disasters created by humans themselves.

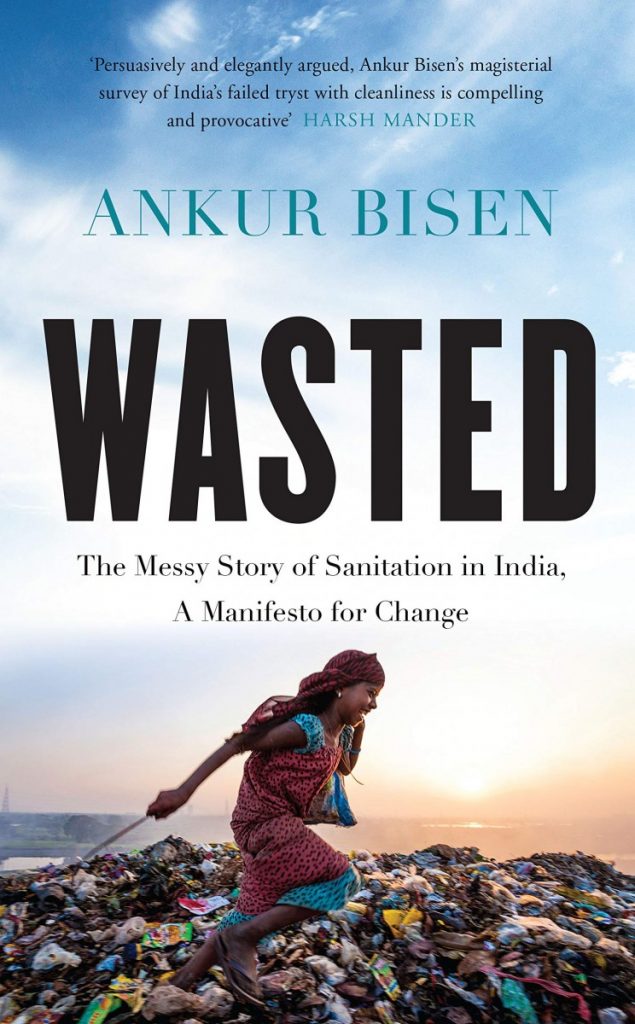

The cover illustration of Wasted is just as captivating as is the book itself. The picture of a child rag picker hopping in a wanton mood on a mound of urban garbage, unmindful of the risk it involves, speaks volumes about ‘the messy story of sanitation in India’.

The book under review problematises waste management in India by disentangling the intertwining caste and sanitation attitudes towards hygiene, and the unabashed defilement of public spaces. Almost the entire landscape of urban India is dotted with untended mounds of garbage, overflowing open sewers, open defecation and urination, piles of plastic bags that mostly find their way to cattle digestive tracts.

The author relentlessly poses hard-hitting questions: Why are Indians so stubbornly undisciplined in keeping their surroundings clean? Why is it so that Indians keep their homes relatively clean while treating public spaces as their rightfully owned dumping ground for all kinds of garbage? Does this have anything to do with the socio-cultural structure of the Indian society? The author tries to provide an insight into the psyche of the Indian society that so unhesitatingly gets accustomed to living in unhygienic neighbourhoods.

Also read: The Stumbling Block of Caste in Solving India’s Sanitation Crisis

The author categorically mentions at the very outset that the book does not have “tables, graphs or charts…because its purpose is not to find facts or to pinpoint villains. For there are no villains in this story, but there are biases and prejudices”. Yet the book is divided into eight chapters and an introduction. Interestingly, as one glances through the bibliography, one notices that most references are from newspapers and journals.

Ankur Bisen

Wasted: The Messy Story of Sanitation in India, A Manifesto for Change

Macmillan, 2019

With barely any book in the reference list, the bibliography reveals the fact that for this pertinent issue not much has been documented or written and this huge gap is what Wasted tries to fill. However, Bisen cites some literary and cinematic works to substantiate his arguments on failed urban planning in India and on the malaise of the caste system that afflicts Indian society at large.

Every library, private or public, should have this book on its stacks for the simple reason that it provides an intensive narrative about the creation of waste (it traces the history behind it), its disposal during the pre-industrial and the post-industrial times, and how, with every technological advancement, humans also create collateral hazardous waste. The author brilliantly brings out the stark differences between the treatment of waste in India and in other countries, mostly from the first world, by juxtaposing their respective sensibilities of hygiene against that of India.

The book attempts to unravel the mystery that surrounds the ambiguous behaviour of Indians about the very concept of sanitation. The twin concepts of cleanliness or purity and pollution are anchored deeply in the socio-religious psyche of the Indian society, and it is not surprising then that this binary opposition of these constructs is treated as the guideline in all banal activities. The private space is treated as pure while the public as impure and polluted.

Furthermore, the problem gets compounded by the caste structure where the cleaning of public spaces is considered to be the duty of the untouchable caste. Such skewed notions about what can remain clean and what cannot are, to a great extent, responsible for the messy situation in India. This practice has been there since antiquity and presumably will remain so even in the future unless Indians stop taking public spaces for granted and start owning responsibility for maintaining public spaces in a manner similar to their homes.

For this to happen there has to be a strong sense of belongingness among every citizen, the feeling that every nook and corner of India is their own, and needs to be treated as such. Can we tolerate anyone who spits betel leaves in our drawing rooms, or could we just let off any individual who urinates in our bedrooms? Then why do we use our streets, roads, public offices, parks and other common spaces to litter, spit, urinate, defecate, and to dump?

Also read: What India’s Next Sanitation Policy Can Learn From the Swachh Bharat Mission

Bisen tries to highlight the stark failure of the state in prioritising sanitation and waste management despite being the world’s largest democracy. What is notable also is the fact that waste treatment was never accorded much importance by the framers of the Indian constitution, or by subsequent governments. However, his remark that India need not suffer from an inferiority complex just because the clean countries of today started their cleanliness drive a century ago is not well-argued. On the contrary, the clean countries of today are clean because of the concerted and combined efforts of both the states and the citizens.

One of the most informative chapters is the penultimate one that educates the readers about the hazards of e-waste, or the new generation waste. India is the third-largest generator of e-waste, after the US and China, and according to an estimate, India annually “generates 2 metric tonnes of e-waste”.

Unfortunately, any legislative effort to acknowledge the hazards of e-waste and make any efforts to arrest its proliferation began only in 2015. India is far more backward than Japan when it comes to handling e-waste, or recycling it by using various processes such as metal extraction. The Indian political class is myopic in its vision that deliberately avoids taking stern measures to handle the hazards of e-waste.

What then is the panacea to make India a clean country? How far has the clarion call for ‘Swachh Bharat’ been able to make an impact on the psyche of the Indian society at large that is so tethered to prejudices regarding caste-based responsibilities, private and public spaces and skewed concepts of purity and pollution?

The author comes up with some viable suggestions in the last chapter, ‘Clean India: Capturing the Chimera’ to help India achieve a degree of cleanliness comparable with that of the first world countries. He suggests that by accelerating the growth of the recycling industry and also by laying emphasis on quality management, India could, to a great extent, address the problem of waste management. Wasted will force us to think twice before we sling or slide poly-bag-filled- garbage on the streets.

Dr Rafia Kazim is an assistant professor at the Department of Sociology at LNM University and a former fellow at CSD.