What Do Gender Roles Look like in a Refugee Camp?

The following is an excerpt from Farhana Afrin Rahman's After the Exodus: Gender and Belonging in Bangladesh’s Rohingya Refugee Camps published by Cambridge University Press

Munni (my research assistant) and I waited one afternoon in late April 2018 in Hamida’s shelter while she was still at the sewing co-operative where she volunteered. Hamida’s husband, Jamil, had welcomed us into the two-room space separated by a flimsy curtain. Hamida’s 12-year-old daughter (the eldest) helped her father with the three younger children. The children were all buzzing in and out of the shelter – her second-eldest child had just come home from his religious class in the mosque, while the toddler sat by Jamil. It was evening by the time Hamida walked into the house – her face underneath her burqa (full body face veil) covered in sweat from the 2-kilometre walk up the hills in the hot summer sun – as dusk was approaching. She brightly walked in, greeting us with a salaam and hugging her children, who ran up to their mother in excitement. She had brought some sweets from her co-operative today and the children rushed off happily, sharing some with the other children in the neighbourhood.

Farhana Afrin Rahman's,

After the Exodus: Gender and Belonging in Bangladesh's Rohingya Refugee Camps,

Cambridge University Press (2024).

Hamida’s weekday mornings were spent completing sewing orders from neighbours and friends. She does the small sewing business out of her shelter – with no sewing machine, she does all the needlework by hand. Much of the sewing she does is through the limited contacts she has through friends and family in neighbouring shelters. She has also taken on volunteering twice a week outside her home as an embroidery teacher – at 11 a.m. she heads out to the co- operative to teach other women needlework, sewing, and sometimes knitting. Though official work opportunities created by the UNHCR in and around the camps are restricted to registered refugees that came in previous waves of migration, the co-operative Hamida works at was set up by a local Bangladeshi NGO that has been keen on setting up opportunities for unregistered Rohingyas after the 2017 mass exodus.

Hamida’s days were constantly filled, and though I spent many mornings with her in her shelter, there was little time to actually sit down and discuss topics at length. After she came home that day, Hamida and I sat down in the second room in her shelter, which doubled as a bedroom with a soft, large foam laid out on the floor as a makeshift bed. We just sat down as her toddler ran in holding onto the bottom of her bazu and Jamil popped his head into the room to say he would be going out and be back late at night. ‘I’m so tired,’ Hamida exclaimed, skillfully tending to her toddler and trying to change out of her burqa all at the same time. Hamida tells me this was the first time she had worked in her life – she was always skilled at sewing but she never thought to turn it into a business until they fled to the camps eight months earlier. Jamil had been a farmer in Myanmar and was the only breadwinner at home at the time. Since coming to the camps, however, Jamil was unable to find work, and though he briefly had a stint as a brick layer in the camps, paid work opportunities were precarious and oversubscribed. While Hamida took up work, Jamil shifted his time between staying in the shelter with the children and sitting in the market with his friends. When he is out, Hamida’s eldest daughter takes care of her younger siblings.

There are so many times that I wonder if I can manage everything. My days are so busy

… there’s so much … and you know us women have many things to do. I am happy to do this work. I mean, look at how many children there are – too many mouths to feed. [She begins whispering and asks her daughter to check if her husband is still in the shelter. She continues once she confirms he has left.] See I have just come home and he has right away given me all the responsibility of the children. I don’t even have time to wash my face. He is at home all day and I am trying to do what I can for the family. Every day I feel less like a woman. Now we women have outside work and also inside work to take care of children – we have to balance everything.

Many of my interlocutors like Hamida struggled to reconcile the new responsibilities and shifting gender roles that come with taking up employment. It was clear that improving the state of women within the community could be tolerated, provided that women continue to perform their traditional gender roles. Changes in traditional male-dominated customs and practices – that is, paid employment – are only positive so long as they remain consistent within a traditional understanding of what is ‘acceptable’ for women.

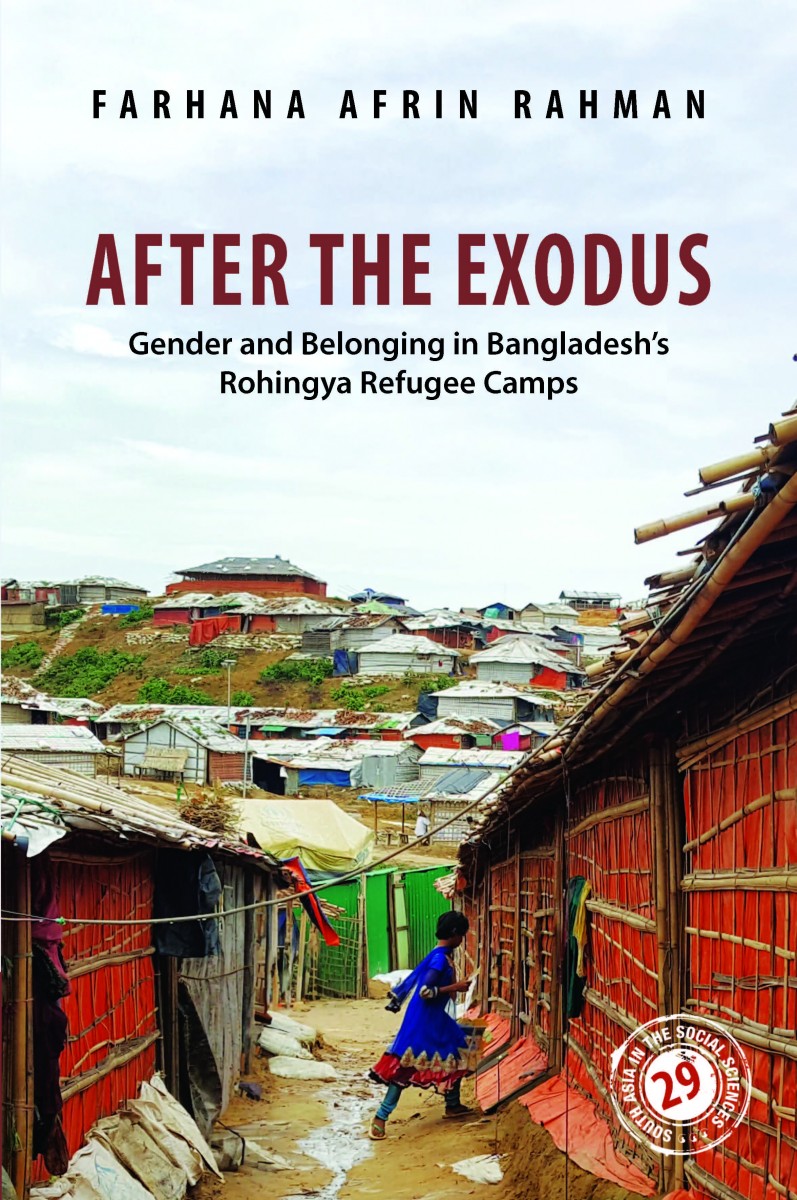

‘Feeling less like a woman’ resonated with many women who were disrupting ‘womanhood’ – or traditional gendered performances of what it means to be a woman – as working outside the home was perceived as a masculine trait. Although there was a sense of relief and ‘happiness’, as Hamida notes to being able to contribute to the household, the feeling of being overworked by taking on both ‘feminine’ and ‘masculine’ roles is something women are having to navigate. As you walk through the narrow pathways in the camp, some Rohingya women are also taking on new roles that were previously associated solely with men back in Myanmar, including working as brick workers to build roads and other infrastructure run by international NGOs.

Ayesha (the woman in her 30s living with her elderly father introduced in Chapter 2) has taken up work as a brick layer. For widows or women with elderly male relatives unable to work, their financial contributions were necessary for family survival, even if it meant the work was something they were not used to before or work that was generally not ‘acceptable’ for women. After a long day in the sun doing heavy labour, she tells me:

When I have to struggle constantly outside and then again at home I do all the cooking and cleaning. I don’t even feel like a woman anymore. Before providing was only the man’s job but not anymore. I used to be a housewife and had no idea about anything outside of the home. This is the first time I have ever done any kind of work like this – look at me! [She begins crying.] I am doing a man’s job now – I never thought I will be working out on the road. It is very painful for me. I was a housewife before. Changing from a housewife to a brick layer is very degrading, but I have no other options.

Women like Hamida and Ayesha spoke of the double-burden of doing masculine ‘work’ and feminine ‘caretaking’. And though the women are navigating these shifting gender roles, they are simultaneously having to come to terms with clearly defined gender roles, which can have a strong effect on the gendered identity of what it means to be a ‘woman’.

The notion of ‘feeling less like a woman’ in many ways, as well, brought with it other gendered reconfigurations within the household. There were some cases where my interlocutors felt that taking on jobs and making financial contributions to the family provided new possibilities and skills that permitted greater ability to negotiate decisions within the household, particularly with their husbands, thereby changing notions of womanhood. This is often done by what Deniz Kandiyoti (1988) considers ‘patriarchal bargains’ where women are able to improve their position for greater autonomy and decision-making. I met Tafura in her shelter one morning while she was completing some sewing tasks. Tafura’s husband was heading out to the bazaar and told her he had taken some money, which she kept safe in a small box under the sleeping mattress. They spent a few moments discussing the finances and budgeted the expenses for the week before he left the hut. She turned to me and said:

Did you see how he let me know that he was taking some of the money? When he was the breadwinner most of the time I did not know how much money we had or even where he kept it. Now I am in charge of safekeeping the money. Did you notice that we discuss these things now? I know it’s not a lot, but it makes me happy that I have something to contribute and he listens to me. I can make some decisions now.

Farhana Afrin Rahman is currently a Leverhulme Early Career Fellow and Isaac Newton Trust Fellow at the Department of Politics and International Studies, University of Cambridge, and a Junior Research Fellow at Wolfson College, Cambridge.

This article went live on September twenty-eighth, two thousand twenty four, at fifty minutes past six in the evening.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.