When a Young Woman Responded to the Ghatam's 'Pukaar'

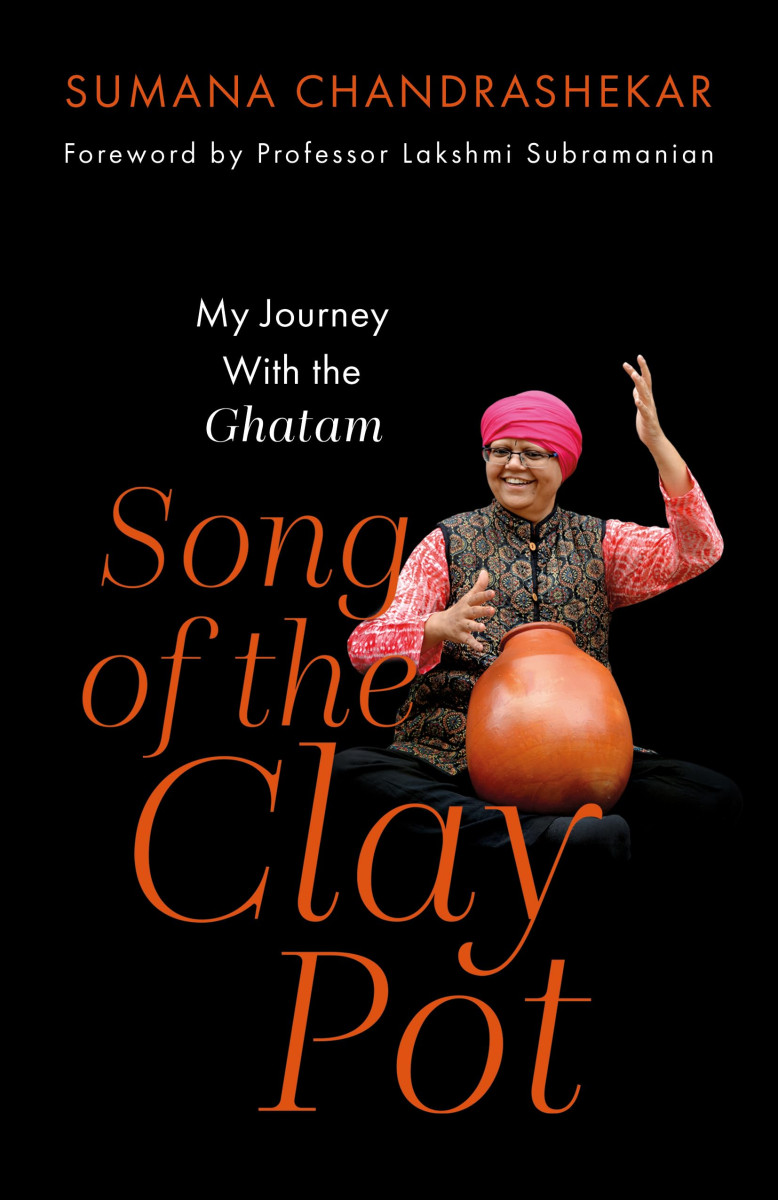

Excerpted with permission from Song of the Clay Pot: My Journey with the Ghatam by Sumana Chandrashekar.

Seeking new livelihood opportunities, [Harihara] Sharma relocated with his family to Madras in 1950. Soon after this, as destiny would have it, he lost the ring finger on his right hand to a freak accident. The window shutter of the tram he was travelling in had come down heavily on his hand. For a mridangam player, the right ring finger is the anchor that supports the entire playing. After the accident, Sharma was unable to play the mridangam again. However, he went on to become one of the most sought-after teachers for learning the mridangam. In Madras, he established a school for percussion which he named Sri Jayaganesh Thalavadya Vidyalaya. The visionary that he was, Sharma even authored one of the first textbooks for mridangam learning. Titled Mridanga Paada Bodhini, the book, written in Tamil, was a pioneering attempt at documenting and structuring existing mridangam pedagogy. It went on to become an important learning aid for students and is even now held in great esteem among learners of Carnatic percussion.

‘It was an unusual and interesting school in the Madras area,’ writes the American scholar Mary Joy Curtiss. In an essay written in 1969, Mary says that the school ‘is directed by its founder, an elderly man who gives all he has to the school’s development. An old elementary school building serves as the teaching area, and the instructors are his sons and former students, who now donate their services to give young boys with no money an opportunity to learn music. The teaching is of excellent quality, and the students love their master. The rhythmic precision of complicated patterns in group performance is unbelievable.’

*

As we now know, it was not just young boys who trained there. A few girls also trained in percussion in the elderly man’s school. A year after this essay was written, Sukanya became a student in that percussion school. This is where she found her life’s true calling—the ghatam.

Sumana Chandrashekar

Song of the Clay Pot: My Journey with the Ghatam

Speaking Tiger, 2025

It was in 1970 that thirteen-year-old Sukanya first stepped into Harihara Sharma’s school, which was only a few buildings away from her house. She had come here not to learn percussion, but to learn violin from Sharma’s younger son T.H. Gurumurthy. Sitting in violin class, however, the young girl’s attention kept flowing into the next room where the senior man was taking mridangam classes. One day, unable to contain her enthusiasm for it, she barged into Sharma’s class and asked if he would teach her to play mridangam. ‘Of course. Let’s start right away,’ he said without hesitation. There was no looking for an auspicious day, no ritual, no offering of gurudakshina. That’s how Sukanya started to learn the mridangam. I think it was this same spontaneous generosity which she had experienced from her teacher, that sprang forth when years later she took me as her student.

We must remember that by this time, the last of the exceptional women percussionists, many of them from families of hereditary musicians and dancers known as the Isai Vellalars, had slowly been side-lined and eventually erased from the new ‘classical’ music scene. We will talk about this a little later. In this new world, girls were not encouraged to learn and play percussion. And yet, Sharma’s school was an exception. Here was a man who believed that ‘the instrument does not know whether it is a boy or a girl playing it.’ So, he taught with no bias. There were a few girls, including a couple of young women from abroad, who learnt mridangam at his school.

Within a few years, Sukanya was a concert performer on the mridangam. However, the most significant transition of her life was yet to come. On that particular day, listening to her guru’s son, Vikku Vinayakram, play the ghatam, she was completely mesmerised.

I often feel that instruments have a way of calling; it is a pukaar, a call, that simply cannot be ignored. When it comes, it feels like a giant wave that gently sweeps over one’s whole being. Once you are awash, there is nothing else to do but to surrender to that pukaar.

So too, drenched in an inexplicable love for the ghatam, Sukanya requested Vikku ji if he could teach her. He politely declined. ‘You have been playing the mridangam so well. Why do you want to change? Being a man, I have myself been struggling to play this instrument. As a woman, you will not be able to play it,’ he warned.

Vikku was well-meaning when he said this. He was not saying that women lack physical strength to play the pot, although that’s what it might seem like at first. Clearly, it was the deeper challenges and undercurrents that he had in mind, which he, in spite of being a man, was already struggling with. But Sukanya was resolute; so was Harihara Sharma, who vowed to nurture her newfound love for the ghatam. In teaching her, Sharma also intended for his school to earn a reputation as a place that willingly taught percussion to girls. And that too, at a time when there was no woman playing the ghatam. Hence, a girl playing the ghatam would be a feather in the cap for his institution. So, while his son was away for a whole year teaching at the Center for World Music at Berkeley, California, Sharma started Sukanya off on ghatam playing. By the time Vikku returned, Sharma had helped Sukanya make a seamless transition from mridangam to ghatam. It was a process of unlearning and relearning many things. So remarkable was the senior man’s pedagogy that when Vikku saw Sukanya play, he was overjoyed and happily took her under his wing.

Vikku’s peers and seniors were not happy with his decision to teach a girl. Many male mridangam players categorically criticised him. They had many reasons—what will society say; women lack the physical strength required for percussion; they will not (be allowed to) play once they get married. In other words, teaching girls/women meant that there is no return on time and effort invested. It would only be a wasteful endeavour—exactly the reasons patriarchal systems use to keep women from pursuing their dreams. But thankfully, like student, like teacher. Despite all the dissuasion, Vikku remained steadfast in his decision. Once he had decided to teach Sukanya, there was no going back.

And thus began a beautiful teacher-student relationship that, over the last five decades, has blossomed and matured. In these fifteen years, I have witnessed and rejoiced at the affection, mutual admiration and respect that threads this guru-shishya bond.

This article went live on October thirtieth, two thousand twenty five, at zero minutes past eight in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.