Why Structural Problems in India–China Relations Persist in the Modi Years

India’s policy towards China during the past decade has been marked by a large measure of continuity along with significant initiatives. This process was disrupted in the summer of 2020.

The Narendra Modi government inherited a complex relationship with China in May 2014 that was simultaneously stable and fraught. The stability stemmed from the fact that the two countries had broadly subscribed to a basic template since 1988, as discussed above.

Decoding China, Ashok K. Kantha, Bloomsbury, 2025.

One major change after the NDA government assumed office was that the leaders of the two countries, Narendra Modi and Xi Jinping, took charge of India–China relations. Until then, it was the Chinese Premier who was the primary interlocutor for the prime minister of India. When I met President Xi during the presentation of credentials as the new Indian ambassador to China in March 2014, he told me that he saw improving relations with India as his ‘historic mission’. Likewise, Modi took a personal interest in the relationship with China, a country he had visited earlier as the chief minister of Gujarat.

In fact, immediately after the Modi government was sworn in, Xi sent Foreign Minister Wang Yi to New Delhi as his special emissary in early June 2014 to initiate preparations for his own state visit to India, which took place in September 2014. In an unusual move, it was conveyed by the Chinese side that Xi would like to commence his visit in Modi’s home state of Gujarat and, if possible, meet him there. In a departure from protocol, Modi travelled to Ahmedabad to receive Xi in a ‘hometown diplomacy’ gesture. Xi reciprocated in May 2015 by receiving Modi in his own hometown of Xi’an. As the Indian ambassador in Beijing, I was closely involved with these two visits.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and the developments in Eastern Ladakh, we had sought a constructive engagement with China. Our leaders met frequently; PM Modi and President Xi had as many as eighteen meetings between 2014 and 2019, including two informal summits at Wuhan (April 2018) and Chennai (October 2019).

These interactions resulted in some key understandings of ‘Closer Developmental Partnership’ (September 2014) and managing ‘the simultaneous re-emergence of India and China as two major powers in the region and the world’ in a mutually supportive manner with ‘both sides showing mutual respect and sensitivity to each other’s concerns, interests and aspirations’ (May 2015).

During the 2014-19 period, there was significant momentum in trade and investment linkages, people-to-people contacts and the deepening and widening of dialogue mechanisms at various levels.

At the same time, India’s concerns and interests were being projected forcefully. Thus, while receiving Xi in Ahmedabad on 17 September 2014, Modi, during a walk along the Sabarmati riverbank, conveyed privately to the Chinese leader his strong concerns regarding the Chinese intrusions in Chumar and Demchok, which had escalated the previous evening. The message registered with Xi, and talks commenced the same evening on the de-escalation and withdrawal of Chinese troops; the status quo ante was restored through a written understanding reached in Beijing later in the month.

In the summit talks in Xi’an in May 2015, Modi pressed Xi on the imperative of an early boundary settlement. The joint statement issued in Beijing the following day ‘affirmed that an early settlement of the boundary question serves the basic interests of the two countries and should be pursued as a strategic objective by the two governments.’

Likewise, subsequent summit meetings were utilised to convey strong messages on a range of issues, including the boundary question, the need to move towards a more balanced economic relationship, India’s membership of the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) and the blocking by China of the listing of Pakistan-based terrorists under the UN Security Council’s 1267 Committee.

Yet the government was acutely aware of the challenges in the relationship.

There was no illusion about the fact that we were dealing with a country that was undergoing unprecedented transformation and was aggressive in its pursuit of unilateral territorial claims and self-defined core interests. India assessed that after the 2008–09 global financial crisis, China had come to the conclusion that the West was in terminal decline and that time and momentum were on its side. Xi Jinping’s ‘China Dream’ of the ‘great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation’, articulated soon after he became the general secretary of the CPC in October 2012, involved the ‘restoration’ of China’s ‘rightful role’ as the leading power in the region and beyond.

There were also serious doubts about whether informal summits were resulting in progress on these structural challenges in the relationship. The Chinese are traditionally averse to using summit-level meetings as platforms for negotiations on contentious issues. It has also been our experience that meetings at the highest level with China have been fruitful only when preceded by extensive preparatory negotiations, including through the deployment of special emissaries.

In its bilateral dealings with India, China was not showing much interest in resolving the boundary question and clarifying the LAC. Likewise, it was not responsive to India’s concerns, interests and aspirations on a range of issues, such as trade imbalance, India’s permanent membership of the UN Security Council (UNSC), its inclusion in the NSG and the listing of known terrorists under the aegis of the UNSC.

Therefore, even while the relations appeared to be on an even keel, ominous clouds were building up due to the accumulation of unresolved issues and irritants. There were structural challenges in the relationship that predated Galwan. This pattern appears to be continuing as there is little evidence of any keenness on the part of China to address those outstanding issues. Let us illustrate with an emerging challenge involving trans-border rivers.

A Xinhua report of 25 December 202428 on the ‘approval’ given by the Chinese government to build the world’s largest hydropower project in the lower reaches of the Yarlung Tsangpo River in Tibet is a reminder of how stubborn issues in the relationship will continue to surface and create fresh complications. According to the Hong Kong-based South China Morning Post, the project is expected to generate nearly 300 billion kilowatt-hours (kWh) of electricity annually, more than thrice the installed capacity of the Three Gorges Dam (88.2 billion kWh), which is presently the world’s largest hydropower plant. ‘Total investment in the dam could exceed 1 trillion yuan (US$137 billion), which would dwarf any other single infrastructure project on the planet.

This decision, apparently taken without any prior consultations with the lower riparian countries, India and Bangladesh, has huge implications for them. Though the exact location of the project has not been officially announced, it is likely to be developed at the ‘Big Bend’ in the Yarlung Tsangpo, very close to the place where the river enters Arunachal Pradesh. This venture will have major downstream impacts on water flows in the Brahmaputra River system in India and further below in Bangladesh. Ominously, the construction of a colossal hydropower plant with a massive impounding of water in an ecologically unstable and earthquake-prone region involves the risk of disaster on an unprecedented scale, as geospatial studies by Dr Y. Nithiyanandam and others have shown.

Uniquely placed as an upper riparian vis-à-vis its neighbours, China has an unfortunate track record of ignoring their interests and concerns with disastrous consequences in the Mekong River basin and elsewhere. As China proceeds with its massive project in Tibet, it is likely to emerge as another major irritant in the relationship.

We must also acknowledge that the worldviews of India and China have become highly divergent. As China’s strategic contestation with the US intensified with the Trump administration beginning to take a more hardline position vis-à-vis China in 2016 and the revival of the Quad in 2017, Beijing was increasingly looking at its relations with New Delhi through the prism of its rivalry with Washington. In 2018, Wang famously dismissed the Quad as nothing more than ‘sea foam’ that would dissipate, but soon the Chinese were voicing their strong concerns regarding the mechanism and India’s participation in the ‘small clique’ diplomacy of the US aimed at countering and containing China.

The bottom line is that in the midst of the geopolitical reordering taking place today, China is possibly the only major country which is not supportive of the rise of India. It is promoting a hierarchical order with China as the pre-eminent power while we favour a multipolar Asia and multipolar world.

It actively hinders India’s interests in South Asia and the Indian Ocean Region (IOR). It is aggressively seeking to project its influence in a manner that is detrimental to our interests. It opposes our permanent membership of the UN Security Council. On its part, China is suspicious of our strategic linkages with the US and initiatives like the Quad which it believes are aimed at containing China.

On the Indian side, there is a realisation that China is not inclined to deliver on the understanding reached in May 2015 that the simultaneous rise of the two countries should progress in a mutually supportive manner. Given the asymmetries in the economic and military power of the two countries, China is not prepared to work towards a relationship between equals.

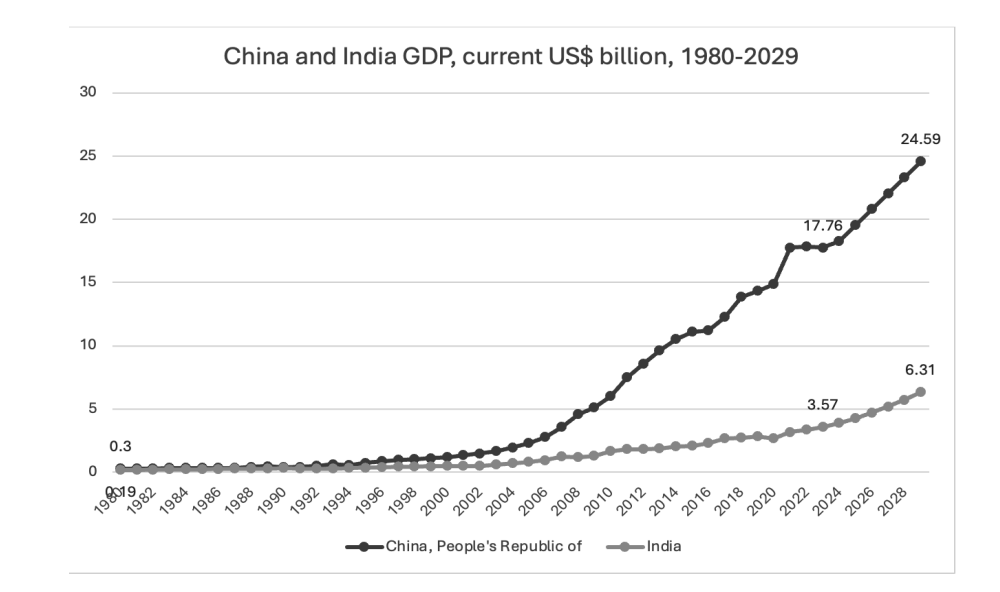

The challenge of dealing with China has been seriously affected by the growing gap in the comprehensive national strength of India and China. Thus, in 2023, the GDP of China was US$17.79 trillion, which was five times as large as the GDP of India at US$3.55 trillion (World Bank data).33 The chart in Figure 1.1 shows how a yawning gap has opened between the GDPs of the two countries, which were broadly comparable until the year 2000:

Figure 1.1 China and India’s GDP (in US$ billion), 1980–2029. Note: 2024–29 are projections of growth. Source: IMF World Economic Outlook, October 2024

Likewise, the defence budgets and capabilities of India and China have become increasingly asymmetrical. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) data for 2023, China’s defence budget was approximately US$296 billion, as compared to US$84 billion for India.

China’s real defence spending is assessed to be significantly higher than its officially acknowledged budget.

Let us look at the growing gap between the capabilities of the Indian Navy and the PLA Navy (PLAN) even though it is an area where we have relatively strong domestic manufacturing capabilities, unlike our ground and air forces, which depend heavily on imported defence hardware.

According to data available from SIPRI and other public sources35, the PLAN surpasses the Indian Navy in both quantity and quality across major platforms. China’s larger fleet – 3 aircraft carriers (2 operational), 41 destroyers, 44 frigates, 71 corvettes and over 70 submarines – dwarfs India’s 2 carriers, 10 destroyers, 13 frigates, 28 corvettes, and 18 submarines.

China now has the largest navy in the world with 370 warships, though the US Navy still has a significant edge in terms of technological sophistication and displacement. India has about 150 warships (including auxiliary vessels), though with much lower sophistication and total displacement value compared to the PLAN. What is more worrisome is the expanding asymmetry in both numbers and quality. Chinese naval shipyards are adding about 20 warships every year while the corresponding number for India is 3–4 ships on average. This gap is progressively eroding the advantage India has in the IOR due to its strategic location and peninsular geography.

The situation along the land borders had become more challenging even prior to 2020. Apart from Chinese intrusions into the Depsang Plains in 2013, and into Demchok and Chumar in 2014, there was a prolonged standoff in the Doklam (Dolam) area of Bhutan in 2017, which was resolved but it proved to be a short-lived respite as the Chinese soon reinforced their deployments and infrastructure within the Bhutanese territory.

One major consequence of what has happened in Eastern Ladakh since the summer of 2020 is that the border issue is back at the centre of India–China relations. The relative calm that had prevailed along the India–China borders for over four decades is unlikely to be restored anytime soon. The borders have become active, with high levels of deployments on both sides. It is the new reality now. The challenge is compounded by the fact that the Chinese have not been ready to clarify the LAC, let alone resolve the boundary question, as they have used the unsettled border as a pressure point in the relationship.

China is not interested in an early resolution of the boundary question for a variety of reasons. The Chinese seem to believe that time is on their side. There has not been any breakthrough in talks on the boundary question between the SRs since April 2005 when an agreement was signed on the political parameters and guiding principles for a boundary settlement. They are demanding ‘meaningful adjustments’ by India in the Eastern Sector, that is, in Arunachal Pradesh (referred to by them as ‘Zangnan’ or ‘South Tibet’), including Tawang, before they will consider making ‘corresponding concessions’ in the Western Sector (so-called ‘dong tiao xi rang’ or 东调西让, translated as ‘adjustments in the east and concessions in the west’).

No government in India can consider making such major ‘adjustments’ in Arunachal Pradesh. The Chinese stance is at variance with the position earlier conveyed by Zhou Enlai and Deng Xiaoping, which seemed to suggest a package solution largely based on the recognition of the status quo in the border areas.

The Chinese have likewise gone back on the clear-cut understanding of the clarification and confirmation of the LAC contained in the bilateral agreements of 1993 and 1996. In the agreement of 7 September 1993, the two sides agreed to ‘jointly check and determine the segments of the line of actual control where they have different views as to its alignment’.

This understanding was further amplified in the agreement on military confidence-building measures (CBMs) of 29 November 1996, which called for the two sides to arrive at a ‘common understanding’ of the alignment of the LAC and agree to exchange maps indicating their respective perceptions of the entire alignment of the LAC as early as possible. The maps were exchanged for the Middle Sector but the process was unilaterally halted by the Chinese side in June 2002 when maps of the Western Sector were shown to each other. The Chinese claimed that we had expanded our claims and refused to exchange maps. There has been no progress in the LAC clarification exercise over the past 22 years.

Differences even on the LAC are now being defined by China in terms of sovereignty. This is a departure from the elaborate architecture of CBMs we have put in place since the Border Peace and Tranquillity Agreement of September 1993, based on the two sides respecting and observing the LAC without prejudice to their respective positions on the boundary question.

There are growing concerns in India about a host of other issues, including the denial of market access to Indian products and services and growing dependencies on imports from China in critical areas. Disruptions in supply chains have exacerbated import dependency on China during the COVID-19 pandemic and underscored the need for resilience in India’s supply sources.

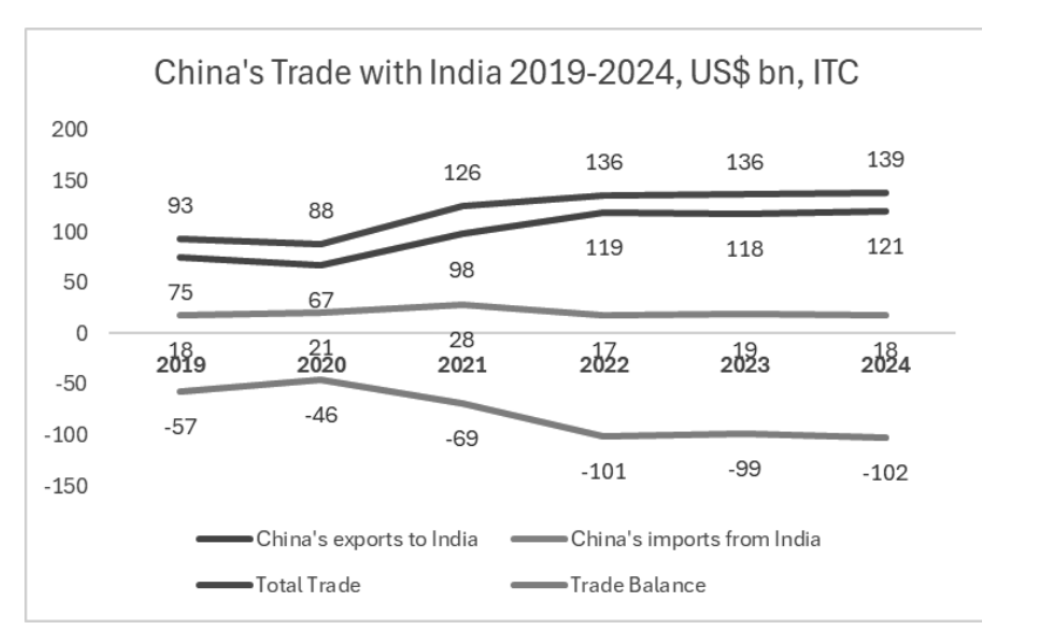

The Chinese are not inclined to address India’s long-standing problem of a huge bilateral trade deficit and the impediments faced by Indian companies in accessing the Chinese market. According to International Trade Centre data, China’s trade surplus with India exceeded US$102 billion in 2024 (up from US$46 billion in 2024); while its exports to India increased from US$67 billion in 2020 to US$121 billion in 2024, its imports from India declined from US$21 billion in 2020 to US$18 billion in 2024 (see Figure 1.2).

There has been no improvement in India’s import dependencies vis-à-vis China in critical sectors like active pharmaceutical ingredients, electronics, chemicals, machinery and green energy products, which is a source of great vulnerability, as China has an established track record of weaponising such dependencies.

Figure 1.2 China’s Trade with India (in US$ billion), 2019–24. Source: International Trade Centre

Even before the Chinese intrusions in May 2020, the policy on welcoming investment from China was being revisited. Thus, Press Note 3 issued by India’s Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade on 17 April 2020 put all foreign direct investment (FDI) from China (and other countries sharing a land border with India) in the prior approval category.37 It was a significant shift in policy.

The government has also taken measures to reduce dependencies on China-dominated supply chains by attempting to build domestic capabilities through production-linked incentives in 14 sectors, tapping alternative supply sources and banning over 350 Chinese apps. This policy of derisking vis-à-vis China will be a difficult and protracted but necessary process. In May 2021, the Government of India decided to leave out Chinese telecom entities Huawei and ZTE from its 5G trials (and the subsequent rollout).

Earlier, in November 2019, India had decided not to join the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) even though it had participated in the negotiations on the agreement.

India decided to opt out of RCEP as several of its key demands were not addressed in the agreement, but concerns about China were possibly the most significant factor in India’s decision. The apprehension was that the Indian market could be overwhelmed by cheaper Chinese goods, adversely affecting India’s manufacturing and agricultural sectors.39 This was compounded by broader geopolitical tensions and trade imbalances between India and China.

Economic security vis-à-vis China has its compelling logic. It would be naïve to expect that China will help build up our manufacturing capabilities, unless it essentially involves assembly of components sourced from China with low-value addition in India.

Indeed, Press Note 3 was introduced prior to the Chinese transgressions in Eastern Ladakh, and the underlying logic has become stronger since then, as there is fragmentation of global value chains, prioritisation of resilience and security, and a progressive shift away from China. There are credible reports of China denying Indian companies access to key equipment (for instance, for fabrication of wafers for solar panels or tunnel boring machines), discouraging electric vehicle manufacturers like SAIC from sharing technology with Indian partners or undertaking fabrication of major components in India, delaying export clearance for components destined for Indian production facilities and even discouraging companies like Foxconn from deploying Chinese technicians at their plants in India. For China, India is not only a geopolitical rival but also a potential manufacturing threat. Our continued caution in economic engagement with China is warranted.

However, the Chinese transgressions in Eastern Ladakh in May 2020 created a qualitatively different situation and a turning point in the relationship. Unlike previous standoff incidents, the Chinese have not restored the status quo as of April 2020, even though progress has been made towards the disengagement of troops, as discussed above.

Despite the understandings reached on the disengagement of troops, the LAC remains live and militarised. The Chinese have stepped up infrastructure building in border areas and India has reciprocated. The infrastructure gap in favour of China remains sizeable and is still increasing. China continues to significantly enhance long-term deployment capabilities along the entire LAC. Three major railway projects coming close to the India-China borders – Nyingchi, Yadong and Gyrong in Tibet – are under development, as are several highways, including G695 in Aksai Chin. The Chinese are prepared for an entrenched military presence close to the LAC.

China’s aggressive behaviour in the shared periphery, land and maritime, has also been a major source of anxiety for India. Some key aspects of China’s approach towards South Asia should be flagged.

One, China has regarded South Asia as a region of interest right since the 1950s but in recent years it has started looking at the region as its immediate strategic periphery. We have seen the evolution of China’s strategic outlook towards South Asia, especially since the convening of the ‘Work Forum on Chinese Diplomacy Towards the Periphery’ by the CPC Central Committee in October 2013.

Frankly, we are struggling to unpack China’s strategic behaviour towards our region. We are not clear whether China seeks expanded influence or whether its objective verges on strategic dominance. China is increasingly entangled in the domestic affairs of our neighbours and is seeking to shape political outcomes.

Two, there is also greater willingness to invest sizeable resources in South Asia under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and its subset, the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). South Asia has emerged as a key component in China’s Maritime Silk Road and Indian Ocean strategies.

However, there are questions about the viability of many of these projects and the ability of the recipients to handle the large debt that these projects involve. Sri Lanka’s debt distress resulted in Chinese entities acquiring the Hambantota Port on a 99-year lease. While handing over the port to China in November 1921, the Sri Lankan government justified the decision to lease the Hambantota Port to Chinese entities as a necessary measure to manage the country’s debt.41 Many of these unsustainable projects have roots in elite capture by China.

Three, China’s trade with South Asia has also expanded but has become increasingly imbalanced in its favour. Thus, according to International Trade Centre data for 2023, China exported US$166 billion to the SAARC (South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation) region and imported only US$23 billion. It had a trade surplus of US$143 billion, of which India accounted for over US$100 billion. Such a skewed trade structure is not sustainable.

Another defining element of China’s engagement with South Asia is defence cooperation. According to SIPRI data, Pakistan and Bangladesh are the top two defence export destinations of China. A combined 63.4 per cent of China’s conventional weapons sales between 2010 and 2020 have found their way to Pakistan, Bangladesh and Myanmar.42 With Pakistan, there is a long history of overt and covert cooperation in strategic sectors like nuclear weapons and missile development.

Finally, as China is the second largest economy and the leading trading nation in the world with a growing presence in different parts of the world, it is not surprising that its engagement with South Asia has also expanded. However, how China expands its presence in our neighbourhood, both land and maritime, matters to India.

There are natural anxieties when projects are undertaken in violation of India’s sovereignty and territorial integrity (for instance, projects in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir). More so as there is a deliberate pattern of India’s vital interests being undermined and the positioning of China as a countervailing force vis-à-vis India comes in the way of the realisation of the potential for intra-regional cooperation.

In the maritime domain, China is progressively deploying a ‘two-ocean’ strategy in the Pacific and the IOR. The Western Pacific, particularly the Taiwan Strait and the first island chain, remains the area of primary interest for China.

However, beginning with anti-piracy operations in the IOR in 2008, the PLAN has gradually ‘normalised’ its operations in our maritime neighbourhood. The Chief of Naval Staff Admiral R. Hari Kumar stated on 1 December 2023 that China now has ‘a sustained presence’ in the IOR with six to eight warships deployed at any given time, apart from research or spy vessels and its fishing fleet.

China now considers its emergence as a maritime power and its protection of overseas interests as strategic priorities. In the Chinese white paper on military strategy released in May 2015, there was a major change in the focus of the PLAN with the addition of ‘open seas protection’ to its existing role of ‘offshore waters defence’.

The white paper stated that the ‘traditional mentality that land outweighs the sea must be abandoned’. This doctrinal shift, the rolling out of the Maritime Silk Road initiative, rapid buildup of PLAN and its assets, major reforms and modernisation underway in the Chinese military, militarisation of reclaimed/augmented features in the South China Sea, near-continuous naval presence and regular submarine deployments in the IOR, development of its first overseas facility and deployment of the PLA Marines at Djibouti in 2017 and other actions taken by China are progressively resulting in a much bigger footprint of the PLAN in the Indian Ocean beyond the Western Pacific, in consonance with China’s stated policy of becoming a maritime power. China’s long-term strategy in the IOR is to move from one of selective sea denial to a strategy of deflective sea control.

However, the Chinese presence in South Asia and the IOR is not necessarily meant as a countervailing force to India; it is increasingly a part of the larger Chinese strategy to expand its regional and global footprint in consonance with its great power ambitions.

In recent months, China has made a tactical outreach not only to the US but also to the European Union, Japan, South Korea, Vietnam and Australia to restore greater stability in those relationships. This tactical flexibility has now been extended to India, though earlier we were an outlier in China’s charm offensive, as was evident from Xi’s absence at the G20 Summit in New Delhi in September 2023 and the fact that the post of the Chinese ambassador in New Delhi had remained vacant for 16 months.

We have discussed earlier the geopolitical reordering that is currently unfolding with unpredictable outcomes. As India prepares to recalibrate relations with China after the understanding on the disengagement of troops in the Depsang Plains and Demchok, and bilateral re-engagement at the highest level, the nature of the challenge posed by China not only to India but also to other major countries, as well as the evolving response of those countries, must be assessed carefully.

This article went live on October ninth, two thousand twenty five, at thirteen minutes past seven in the evening.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.