Atmanirbhar or Import-Friendly? Why India's Industrial Policy Is a Dilemma

The Union government's decision to impose a licensing requirement on the import of laptops has received considerable traction in the industrial policy discourse. Now, there is news that the government will not impose a licensing requirement but will introduce an import management system to regulate the imports of laptops in the country.

Frequent changes in policy decision not only contribute to policy uncertainty but significantly undermine its international reputation as a reliable trading partner. There are speculations that it may impose similar import management system on cameras, printers, hard disks, parts of telephonic and telegraphic devices.

This has heightened the debate in the country regarding the nature of industrial policy that India is pursuing under its self-reliant India, or Atmanirbhar Bharat, initiative.

The contemporary debate on industrial policy is centred around production-linked incentives (PLIs), trade policy, and non-tariff measures. The extensive use of these instruments falls into the broader industrial policy sphere and aims to augment the capacity, competence, and capabilities of domestic manufacturing with the objectives of reducing imports, creating jobs, and mobilising investments.

The nature and design of industrial policy undoubtedly needs intense debate for informed industrial policy choices. The key question for a country embarking on a path of industrialisation is whether it should use policies that conform or defy its comparative advantage. Conforming strategies eschew government interventions and limit the role of state to a facilitator, while defying strategies advocate government interventions and support infant industry protection for industrial upgrading.

The contemporary debate on industrial policy needs to examined along these lines. The industrial policy practice in India is by and large supporting the defiance of strategies, given the usage of policy instruments such as import tariffs, licensing requirements, quality standards, import restrictions, and subsidies to protect and support the domestic manufacturing industry. The justification of using trade policy as an instrument for industrial upgrading is based on the concept of dynamic comparative advantage and the infant industry argument, as well as other reasons such as market failure, economic nationalism and national security concerns.

Also read: FY23: India’s Imports From China Up 4.16%, Exports Down 28%, Trade Deficit at $83.2 Billion

The industrial policy practice through the PLI scheme is biased towards capital-intensive industries such as automobiles, pharma, advanced battery cells, telecom equipment, speciality steel among others. Despite having comparative advantages in labour-intensive manufacturing activities, India’s policy priorities have resulted in the commodity composition of exports becoming biased towards capital and skill-intensive products.

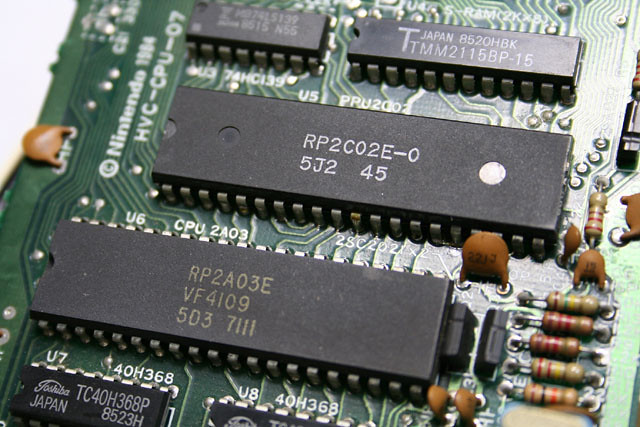

A semiconductor chip. Photo: VCU Capital News Service/Flickr (CC BY-NC 2.0 DEED)

This is particularly true in the case of semiconductor manufacturing, where it more effectively contributes to the "design" segment of the semiconductor manufacturing value chain given its large pool of qualified engineers. This does not mean that India should not focus on chip manufacturing but it needs to identify specific areas in the semiconductor value chain where it has comparative cost advantage and can contribute efficiently. This requires making the industrial policy coherent with optimal industrial structure that is inherent to the country's endowment in terms of the relative abundance of labour, skills, and capital.

There is a need to develop a coherent industrial policy that aims at increasing the domestic value-addition within the economy, creating links between the foreign firms and domestic suppliers, and facilitating technological upgrading and spillovers from foreign direct investment (FDI). It is important policymakers expand the scope of the PLI scheme and include labour intensive sectors such as leather, garment, light engineering goods, toys, and footwear. This is critical to scale up the domestic manufacturing in these sectors and generate employment and build industrial capabilities.

The role of government is to foster an enabling environment to ensure that the economy is embarked on this endogenous process of upgrading so that firms and sectors are able to leverage the country’s comparative advantage. This naturally allows firms to advance organically. As firms become more competitive, they make efforts to capture market share, generate maximum economic surplus through profits and earnings, and reinvest to earn the highest possible return, given that the industrial structure is consistent with the endowment structure. Such a strategy enables the economy to amass physical and human capital, thus contributing to the upgrading of the endowment structure. This gradually makes domestic firms more competitive, subsequently venturing into capital intensive manufacturing.

India's industrial strategy under Atmanirbhar Bharat needs to ensure that financial incentives are extended to sectors or firms that foster strong domestic inter-sectoral linkages and facilitate industrial upgrading. These sectors or firms will generate a real economic surplus for the broader economy which will also contribute to the effective utilisation of the factor of production as well as their advancement for upgrading industrial structures. Such a strategy will ultimately deepen domestic manufacturing capabilities, thereby creating possible opportunities to plug in global production networks.

If done strategically, PLIs could foster domestic champions, but it is important for Indian policymakers to make sure that the sunset clauses are clearly stipulated in the PLI scheme with a reasonable timeframe. There is also a need to revisit industrial policy stance, particularly with respect to the use of policy instruments and making it more coherent with the comparative cost advantage that lies in its factor endowments.

Surendar Singh is an Associate Professor at FORE School of Management, New Delhi, Karishma Banga is a Research Fellow at the Institute of Development Studies, UK. Views are personal. They can be contacted at drsurendarsingh@gmail.com and k.banga@ids.ac.uk.

This article went live on October tenth, two thousand twenty three, at six minutes past three in the afternoon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.