Whose Growth Is it, Anyway? Understanding India’s Infrastructure Push

New Delhi: After 11 years at the Centre and over Rs 54 trillion spent on capital expenditure, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s emphasis on infrastructure as a catalyst for growth and employment has benefitted the private sector and created a new class of nouveau riche contractors at an unprecedented pace in the country’s history.

In the Union Budget for 2025-26, India’s Union government allocated Rs 11.2 lakh crore towards capital expenditure projects including roads, highways, ports, energy, railways and metros, and urban and rural development. That is over one and a half times more money than what was allocated towards education, healthcare, social welfare schemes and programmes that support the bottom half of India’s populace, such as the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS), National Health Mission, affordable housing and skill training.

Privatisation and multi-million dollar tenders from the government have created new pockets of wealth among infrastructure players across the country. But there is scant data on who these business persons are, and few have analysed the gamut of the contractor economy that benefits from government largesse.

“Data which makes people ask uncomfortable questions is seldom available,” said Mohan Guruswamy, policy analyst and former finance ministry advisor. “In India, the guy who becomes rich is the guy who works the system.”

India’s ‘growth’ model

While private involvement is visible in tenders and contracts awarded, questions regarding market concentration and political patronage are largely ignored.

“All government expenditure at one level or the other flows into private hands,” said Guruswamy, adding that the purpose of government expenditure is to create economic activity, and the outcome is that it flows into private hands, whether by wages or other means.

“But when you talk about money flowing into the hands of a few people, then it becomes problematic. That seems to be the problem – that it is cornered by certain contractors, certain business houses, and the money stays there instead of going further down. The money stops there.”

Recent developments in Gujarat indicate how such political linkages can shield powerful actors from accountability even when public money is misused: In April 2025, Kiran Khabad – the son of Bachubhai Khabad, Gujarat’s minister of state for panchayat and agriculture – was re-arrested in connection with a Rs 71 crore scam under the MGNREGS in Dahod district.

Investigations revealed that Khabad and his brother, through their agencies, allegedly claimed payments for incomplete or non-existent rural employment works by submitting forged documents and bogus certificates. Despite multiple FIRs and evidence, the minister himself remains untouched by legal proceedings, raising questions about political immunity and systemic opacity in the disbursal and oversight of welfare funds.

Also read: Desert Lands of Rajasthan Being Taken for Solar Power Plants; Residents are Upset

The trickle-down effect may be limited to a handful of big companies when it comes to large projects, while at a state and municipality level many contractors are often politically connected. “Almost all MLAs have contract linkages, and then you have large civil contractors who farm out work and pocket the margins,” Guruswamy said.

An Indian Express investigation found that a 2022 tweak in the government’s flagship Jal Jeevan Mission’s tender guidelines led to massive unchecked cost escalations, adding nearly Rs 17,000 crore in extra expenses across thousands of rural water supply projects – and bringing to the fore large concerns about transparency and fiscal discipline in India’s infrastructure programmes.

As government expenditure on infrastructure has increased over the last decade, so has the composition of India’s largest and most valuable companies. For instance, the value of companies in industrial products, energy, real estate, construction materials, transportation and logistics, and construction and engineering grew to Rs 7.6 lakh crore in 2024 compared to Rs 3 lakh crore in 2020, according to the 2024 Burgundy Private Hurun India 500. As a result, the composition of India’s billionaire class has reflected this power dynamic, with new billionaires emerging from similar industries.

Similar to Adani Group founder Gautam Adani’s rise over the last decade and more – which has been fueled by privatisation, patronage and public investment leading to private accumulation – the founder of Hyderabad-based Megha Engineering and Infrastructure Ltd, P.V. Krishna Reddy, has emerged as one of India’s most influential magnates.

“While traditionally, MEIL was majorly involved into irrigation and drinking water projects (52% of total orderbook), it has now diversified its operations to various other segments like hydrocarbons (11%), power (13%), roads (18%) and others which has opened avenues for revenue growth,” according to a November 2024 rating note.

The company also has a listed Electric Vehicle bus maker Olectra Greentech Ltd and a joint venture with Shenzen-based BYD. Its major projects include the Polavram Dam project, Zojila Pass tunnel, a government-to-government refinery project in Mongolia, major highway contracts across the country, and several road contracts in Mumbai.

Megha’s success in bagging tenders and infrastructure projects over the last decade has grown the group’s valuation and its founders’ wealth, which stands at $2.2 billion as per Forbes. The company’s order book has grown seven times to Rs 2.28 lakh crore as of November 2024 from Rs 33,775 crore ten years prior. In 2023-24, it made Rs 2,937 crore in profits after tax compared to Rs 495 crore a decade earlier.

However, the rise of Megha Engineering has not been without controversy. After the Supreme Court mandated the release of electoral bond data in early 2024, it was revealed that Megha Engineering was the second-highest donor contributing Rs 966 crore in funds to political parties during the life of the campaign finance channel. Of this, Rs 584 crore went to the Bharatiya Janata Party and Rs 195 crore to Bharat Rashtra Samithi (formerly Telangana Rashtra Samithi) from its home state.

More recently, the Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority (MMRDA) decided to scrap the contract for the Thane-Ghodbunder to Bhayandar tunnel and elevated road projects after the Supreme Court intervened. Rival infrastructure giant Larsen and Toubro challenged the MMRDA’s award of the Rs 6,000 crore project to Megha Engineering, arguing that MEIL’s bid was significantly higher.

With countless hurdles in a system which relies on a combination of highly informal, politically well-connected players and large oligopolies like Adani and Ambani, it would be foolish to imagine that market mechanisms are working, according to Rathin Roy, the former advisor to the Prime Ministers Economic Advisory Council.

The government’s strategy on infrastructure strategy continues to rely on political patronage and negotiated outcomes rather than productivity or market efficiency, he said.

“One way to improve [infrastructure] productivity is for the people who run the government not to make small amounts of money on every kilometre of road built, with everybody having a stake in that,” he said.

From government to private coffers

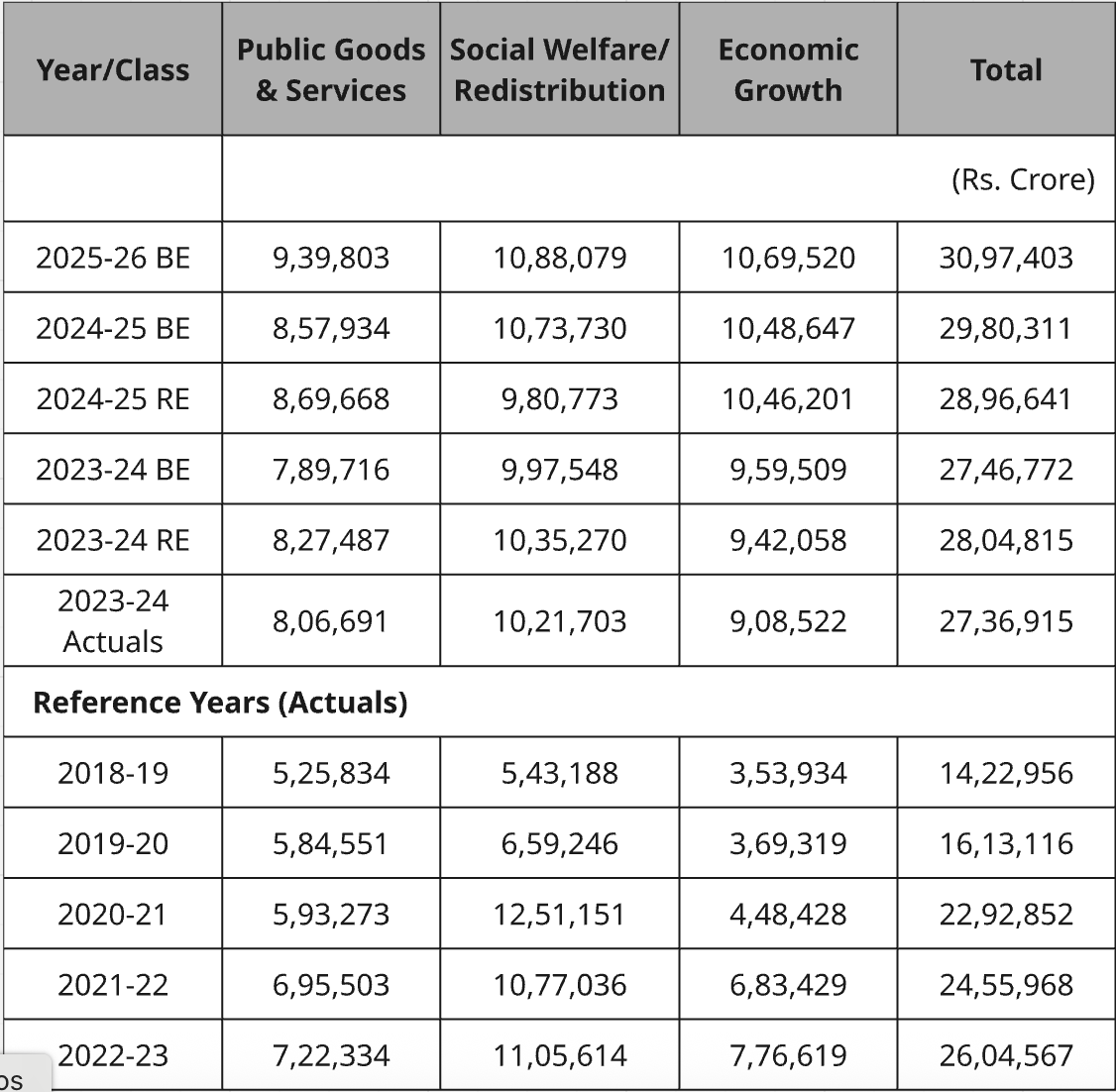

In his recent book Commentary on Budget 2025-26, former finance secretary Subhash Chandra Garg broke down government expenditure into three major buckets: public goods and services, welfare and redistribution, and economic growth. He found that amounts spent on redistribution and on “growth” are nearly equal, meaning that transfers to industry are just as large.

Economic growth expenditure has increased every year since 2018-19, and since 2021-22, these expenditures exploded on the back of the government’s emphasis on a capital expenditure-based economic growth mode, he writes.

“There’s so much debate in the country about ‘freebies’, social expenditures, and so on,” Garg told The Wire. “But very few people talk about the transfers to industry, represented by the growth expenditure – despite that being more or less of the same order as the entire redistribution expenditure.”

Garg uses the term “economic growth expenditure” to describe outlays that flow directly or indirectly into private hands. His analysis found that the private sector received Rs 9.08 trillion from government coffers in FY2023-24. In the 2025-26 budget, the same rose to Rs 10.7 trillion.

“The [standard budgeting] system doesn’t provide details of what government expenditure goes towards the private sector. Government could redesign the system to do it, but I don't see any intention of the government to do it,” Garg said.

Source: Commentary on Budget 2025-26 by Subhash Chandra Garg

Roads to riches

Among India’s infrastructure priorities, roads rank just behind railways in budgetary allocations – but they lead in terms of project execution and private sector participation. Over the past decade, the National Highways Authority of India (NHAI) has grown into one of the country’s most powerful infrastructure agencies, overseeing tens of thousands of kilometres of highway expansion and managing an annual outlay that rivals entire state budgets.

With the adoption of new contracting models and consistent central backing, NHAI has become a financial behemoth – and a magnet for private capital.

According to infrastructure tender data compiled by intelligence platform Nexizo.AI, private companies won Rs 53,983 crore worth of highway contracts in January 2025 alone – about 58% of the total value awarded that month. In recent years, private firms have consistently secured more than half of the awarded value in roads, largely through EPC (Engineering, Procurement, and Construction), HAM (Hybrid Annuity Model), and TOT (Toll-Operate-Transfer) contracts.

“National Highways Authority of India’s TOT auctions have drawn strong global players – Brookfield, Macquarie, IRB Infrastructure,” according to Naina Bhardwaj, international business advisory manager at Dezan Shira & Associates. “That speaks to the credibility and monetisation potential of Indian road assets.”

Also read: India’s High Growth Paradox

The pace of road and highway construction by NHAI and state-level authorities over the last decade has been unprecedented. Yet, the burden of funding for road construction has been on the public exchequer through the NHAI, which faced concerns of over-indebtedness. While the agency has cut its debt over the last year to Rs 2.8 lakh crore, it is no longer borrowing from the market and is relying on budgetary support to fuel new construction, according to PRS Legislative Research.

All the while, private sector investments in the sector are still lagging due to financing risks. “Most developers have significantly leveraged their balance sheets in anticipation of high levels of growth. This has affected the debt servicing ability of private developers,” states the legal think-tank.

“Aggressive bidding results in private developers bidding at prices lesser than the value estimated by the authorities, to gain the project. This has led to projects being awarded to concessionaires who may not have the requisite capacity to raise finances."

But in spite of these shortcomings, the handful of private players who have been successful in building out highway projects have been rewarded by large market valuations.

A handful of contractors have captured the bulk of this private participation, and their order books have expanded in size over the last decade. For example, H.G. Infra Engineering’s sanctioned order book stood at Rs 15,080 crore as of December 2024, nearly three times its FY24 revenue, primarily from government projects and more than triple its order book of around Rs 4,860 crore in FY18.

Other major players including PNC Infratech (2010 to 2024-25), G.R. Infraprojects (2015 to 2024-25), Gayatri Projects (2008-09 to 2019), Afcons (2011 to 2024) and IRB Infrastructure (2010 to 2024) have seen their order books grow from Rs 2,000 to Rs 10,000 crore in the early 2000s and mid-2010s to Rs 15,000 to Rs 35,000 crore in recent years, largely driven by NHAI’s HAM/EPC mandates.

Green machine

India has made notable progress in expanding its renewable energy (RE) capacity over the past decade, driven by a clear policy push and ambitious national targets. The share of renewables in the country’s energy mix has risen steadily, helped by falling technology costs and a pipeline of government-backed auctions.

The Solar Energy Corporation of India, the central agency anchoring the bulk of India’s RE auctions, has awarded a significant share of its contracts to private developers such as ReNew Power, Adani Green, ACME Solar and Azure Power – all of whom have built sizeable portfolios.

As of April 2025, renewable energy – including hydro and sources under the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) – accounts for over 18 GW of capacity in the central sector and a staggering 175 GW in the private sector, Central Electricity Authority data shows. This underscores the private sector’s dominance in India’s clean energy landscape, even as central agencies like NTPC and NHPC remain key players.

Among India’s top 25 listed power generation companies as per Screener, state-owned firms still dominate installed capacity, but private players now capture a significant and growing share of market value.

While government PSUs like NTPC and NHPC still lead in installed capacity, private players – particularly renewable-first firms like Adani Green, JSW Energy and KPI Green – now account for over 35% of the market capitalisation of India’s top power producers, based on data from Screener.in.

Per Nexizo.AI, private players won Rs 84,708 crore worth of renewable and nuclear power contracts in 2024 – over 75% of total awarded value. Since 2019, and barring 2021, the private sector has consistently secured nearly 70% of renewable and nuclear project tenders.

“On paper, India’s tax incentives and Viability Gap Funding mechanisms are quite robust,” said Bhardwaj. “But in practice, the effectiveness varies depending on the project structure, executing agency, and states’ administrative capacity.”

According to data from the Central Electricity Authority, companies like Adani Green, ReNew Power, NTPC, Tata Power Renewable Energy and Azure Power collectively control a significant share of India’s installed and under-development clean energy portfolio.

Adani Green alone accounts for over 12 GW of operational renewable capacity, with 30 GW under development at Khavda in Gujarat – slated to be the world’s largest power plant across all energy sources – and a target of achieving 45 GW by 2030. This concentration suggests that while India’s auction-based model has successfully attracted capital, market power remains tilted toward a small club of well-capitalised firms.

Policy rethink

The economic logic for investing in infrastructure is simple. It attracts private capital and can create local employment opportunities, while subcontracts from a large company can redistribute money across adjacent industries and trickle down to small and medium enterprises. In the medium to long term, the project improves lives and livelihoods, and encourages economic activity, leading to more tax revenue.

But if government spending overwhelmingly benefits a few large players, it risks entrenching monopolies and exacerbating inequality. Especially if the policies are not mindful of fair competition, do not enforce contractual conditions and ignore the interests of smaller businesses, workers and consumers.

The Union government, alongside states, accounted for 78% of all infrastructure spending between FY2019 and FY2023, whereas the private sector contributed just 22%, according to Naina Bhardwaj, international business advisory manager at Dezan Shira & Associates.

“That suggests that public money is doing the heavy lifting, but private capital hasn’t responded in proportion,” she said.

A major selling point for infrastructure spending is job creation. In 2023, India’s construction sector employed over 71 million people, with projections touching 100 million by 2030. A 2024 report noted a 36% rise in employment from 2016-17 to 2022-23.

According to a BJP document, for every Rs 1 crore spent, 200 to 250 man-years of employment are generated, but official labour data tells a more sobering story: most of these jobs remain informal or contractual. Even as the government increases its infrastructure outlays, data from the Periodic Labour Force Survey shows that job creation retains a significant share towards informal or contract roles.

Under the government’s National Infrastructure Pipeline, projects worth Rs 185 trillion are in the pipeline, according to a March 2025 note by ICRA. However, only 20% were completed as of March 2024, with work underway on 45%. The vast majority of the projects – 99% – are executed by government entities, with private sector participation accounting for under 1%.

While infrastructure spending may boost GDP, its long-term impact on livelihoods and social indicators remains unclear at best.

“I’m never very clear what this government wants to do,” said Roy. “You can only evaluate a policy through the objectives of that policy, but I’m as yet unaware of the objectives the government of India’s infrastructure policy. If it is growth, infrastructure growth is neither necessary nor sufficient for growth.”

Anisha Sircar is a journalist and upcoming author, formerly deputy Asia editor at the Reuters Global Markets Forum, with previous experience working at Bloomberg, Scroll.in and Quartz. Her work examines the intersections of global finance, tech, and society, and she holds a master’s degree from Columbia University.

This article went live on June eleventh, two thousand twenty five, at twenty-one minutes past seven in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.