Haunted by the Past: Why 6,000 Families from Andhra's Stuartpuram are Desperately Seeking Help

Stuartpuram (Andhra Pradesh): Seventy years after the first independent government of India de-notified the communities criminalised by British colonisers under the Criminal Tribes Act, 1871, members of the Erukula community in Andhra Pradesh are still in dire need of rehabilitation.

In Stuartpuram, a colony located on the margins of National Highway 16 that links Kolkata and Chennai, 6,000 families of the Erukula community still live with the social status thrust upon them more than a hundred years ago by the British as members of 'a criminal tribe'. Though this designation was removed in 1952, it remains key among several factors that keep the community down, even though some among them have risen to great heights in fields such as bureaucracy, politics, medicine and sports.

For example, Karreddula Nageswara Rao, a rickshaw-puller turned criminal who faced 70 charges of grave dacoity in his time and surrendered to the police in 1984, is so much at a loss for a means of earning a living that he is contemplating a return to crime. Meanwhile, his wife, Marriyama, also a former criminal, is so desperate to find work for her 45-year-old son that she approaches any new face in the colony for help.

“We gave up the profession we inherited from our ancestors and we are not able to take up alternative livelihoods. We are now at a crossroads,” Rao told The Wire. "I wanted to start a timber depot when I gave up crime. For that, I expected financial help from the government, but it failed to come through. Though I was given 70 cents of cultivable land on lease in Stuartpuram (70 cents = 0.70 acres) and 200 yards for a house as part of the rehabilitation package, agriculture failed to be viable for a number of reasons. Later, I was forced to sell the land to raise money for my daughter's wedding."

A history of ups and downs

Stuartpuram has been a rehabilitation colony for members of the Erukula tribe since 1910, when Harold Stuart, the home member of the then Madras government, tried to improve the lives of the community by providing them with land for agriculture and employment at the Indian Leaf Tobacco Limited company. The colony was one of 11 settlements established for the welfare of the tribe, including Sitanagaram in old Guntur district, Bitragunta in Nellore district and Aziz Nagar in South Arcot district. An elementary school was established there at the time of the British, which was later upgraded to a high school, and a cluster of intermediate and degree colleges came up at Cheerala and Bapatla, just seven kilometres away.

Also read: For NT-DNT Communities in Maharashtra, Swachh Bharat Has Not Brought Clean Toilets

At the entrance of Stuartpuram, an arch bearing the names of Harold Stuart and Hemalatha Lavanam, a social activist who strove to reform the so-called criminal tribe, welcomes visitors to the colony. Beside the arch is an imposing statue of Ekalavya armed with a bow and arrow, since the Erukula people identify with this icon of forest and hill tribes in the epic Mahabharata.

The colony occupies 12,000 acres of land at the tail end of the Krishna canal system, which makes cultivation fraught with risk. It doesn't help that Nageswara Rao, like many others in the colony, has never been an agriculturalist since the Erukula people are primarily nomadic.

A view of Stuartpuram. Photo: Gali Nagaraja

In the 112 years of its existence, Stuartpuram has seen its settlers thrive and fail. Some big names in the Indian polity and bureaucracy have emerged from the colony, like the late Karreddula Kamala Kumari, who served as the Union welfare minister in the Congress government of 1991. Other success stories from the settlement include doctors, engineers, bank officers and state and Central government officers. But as with many marginalised and downtrodden communities, only a few members manage to climb the rungs of social hierarchies. In Stuartpuram, the majority of the population live with the stigma of criminality.

A certain reputation

The stigma persists perhaps because the government settles only members of the Erukula tribe in Stuartpuram. No other communities are accommodated in this colony, which gives it a certain reputation.

"The stigma we inherited from our forefathers still makes our lives miserable," said Mogili Madhu, a resident of Stuartpuram. “I wanted a loan for a two-wheeler. But the private financier I went to denied me the loan, saying it was because I am a resident of Stuartpuram."

Madhu said he played kabaddi at the national level, but failed to get a job through the sports quota. So he joined the Home Guard in the police service. "I felt compelled to resign from the job because senior police officers tried to use me to launch a crackdown on our colony due to its reputation," he said. He is now an activist with the ruling YSR Congress party in Andhra Pradesh.

Whenever petty offences like chain snatching take place in areas outside Stuartpuram, the police search Stuartpuram first, said Mogili Hari Babu, president of the mandal parishad and resident of Stuartpuram. "Financial institutions deny us loans by underlining any Stuartpuram address in red ink," he added.

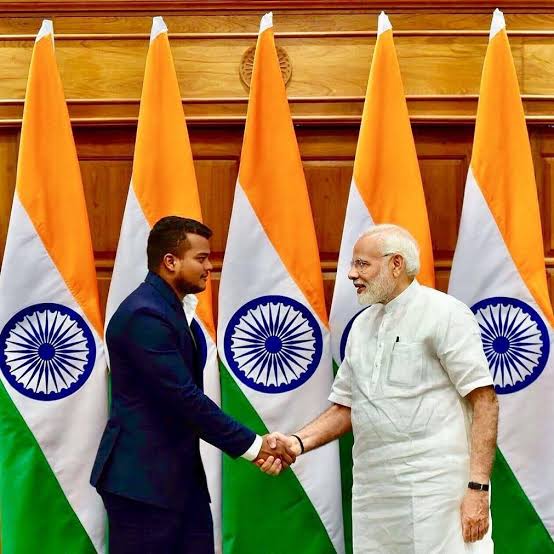

Prime Minister Narendra Modi congratulating Venkata Rahul from Stuartpuram in Andhra Pradesh for winning two golds in weightlifting in the recently held Commonwealth Games.

Elsewhere in the colony, Madhu Ragala, a kabaddi player and weight-lifting champion with 14 medals to his credit, feels just as let down as Mogili Madhu. Representing the first non-criminal generation of his family, Ragala groomed his two sons to be sports champions, but though they have done well, they have not received material recognition from the government. His elder son, Venkat Rahul, a weight-lifting champion, won two gold medals in the Commonwealth Games and his younger son, Varun, also a weight-lifter, participated in the Asian Games. Former chief minister N. Chandrababu Naidu had promised Varun a government job and land for a house, but nothing came of this when the government changed, Ragala complained.

Mogili Madhu's claim that the police judge Stuartpuram by its reputation was reinforced on December 16 when a posse of police personnel from Bapatla and Cheerala, accompanied by personnel from the prohibition and excise department, conducted a raid on the colony to verify the movements of ex-criminals while investigating pending cases related to the brewing of illicit liquor.

Intervention required

According to experts, members of the Erukula tribe turned to crime after the British established rail and road networks through the Madras Presidency in the 1850s, depriving them of their traditional livelihoods as itinerant traders.

Also read: Creators, Not ‘Criminals’: Children of Denotified Kuravar Tribe Speak Through Art

Prathipati Devavaram, who served as a doctor in Stuartpuram for a long time, told The Wire that the mechanisation introduced in the Indian Leaf Tobacco Division also displaced a large number of the Erukula.

Aside from the government policy of settling former criminals from the Erukula community in places like Stuartpuram, the only rehabilitation package available to members of the community comes from the police and covers only those who make illicit liquor.

"The police identified half a dozen persons making illicit liquor from Stuartpuram for financial help to get into alternative livelihoods like dairy and petty businesses," Vakul Jindal, superintendent of police, Bapatla, told The Wire.

This is why P. Samuel Jonathan, the Right to Information commissioner, highlighted the need for continuous intervention from the state to ensure that members of de-notified tribes are properly integrated in mainstream life.

“The absence of such interventions may drive members of the tribe to return to crime,” Samuel told The Wire. He said he would request the district collector to implement welfare programmes in a convergence model exclusively for Stuartpuram to introduce vocational trades for unemployed youths, draft women into self-help groups, help with housing and so on.

Nageswara Rao lamented that even the money he robbed in his years in crime had failed to bail him out of poverty.

“It’s only the police, gold merchants and lawyers who benefit from our booty,” Rao observed. “Look at my wife. She is not even wearing ear studs, though I stole gold and cash in huge amounts within and outside the state for more than two decades.”

§

Clarification issued on December 21, 2022

An earlier version of this article included a quote from Dr Meena Radhakrishna, which has been removed after publication as her work had been misquoted. Here is a note from Radhakrishna:

"This author has wrongly attributed to me the "observation" that the Yerukulas of Stuartpuram had turned to crime in the 1850s because they lost their ancestral itinerant trade after the introduction of railways. The author has written as if he is quoting from my writings, which is highly objectionable since I did not write the quoted words in either my book or any of the articles, nor draw the conclusion attributed to me.

What I have tried to document in my book Dishonoured by History: ‘Criminal Tribes’ and British Colonial Policy (referred to by the author) is the historical background to the institution of the Criminal Tribes Act, 1871. My research shows that the British authorities began to consider itinerant communities as criminals after they lost their traditional livelihoods; the colonial authorities drew the spurious and false connection between loss of livelihood by a community and its natural gravitation towards crime for sustenance. This is how the itinerant communities' loss of livelihood became a justification for bringing them under the Criminal Tribes Act. There is no evidence whatsoever I found during my research, on which the book and several articles are based, that the Yerululas' traditional loss of livelihood led to their adopting crime as means of livelihood. This is the author's own conclusion, through misreading and misinterpretation of snippets of my research."

Gali Nagaraja's response:

"In the process of gathering of information the writer referred to various sources including the elders of the community, experts who have knowledge about the living conditions of the community and missionary members who worked with the community for a long time and literature produced by authors and research scholars. Quoting various sources, this writer has expressed the view that advent of modern transport robbed the community of their traditional livelihood, ultimately compelling them to adopt anti-social way of life.

However, Dr Meena Radhakrishna, writer of the book Dishonoured by History: ‘Criminal Tribes’ and British Colonial Policy has clarified that she had never subscribed to the view that “deprivation of livelihoods compelled them to take to crime”. I apologise for the fact that my original story created a wrong impression about this."

This article went live on December nineteenth, two thousand twenty two, at fifty-one minutes past eight in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.