It’s Time to Ambedkarise Public Policy

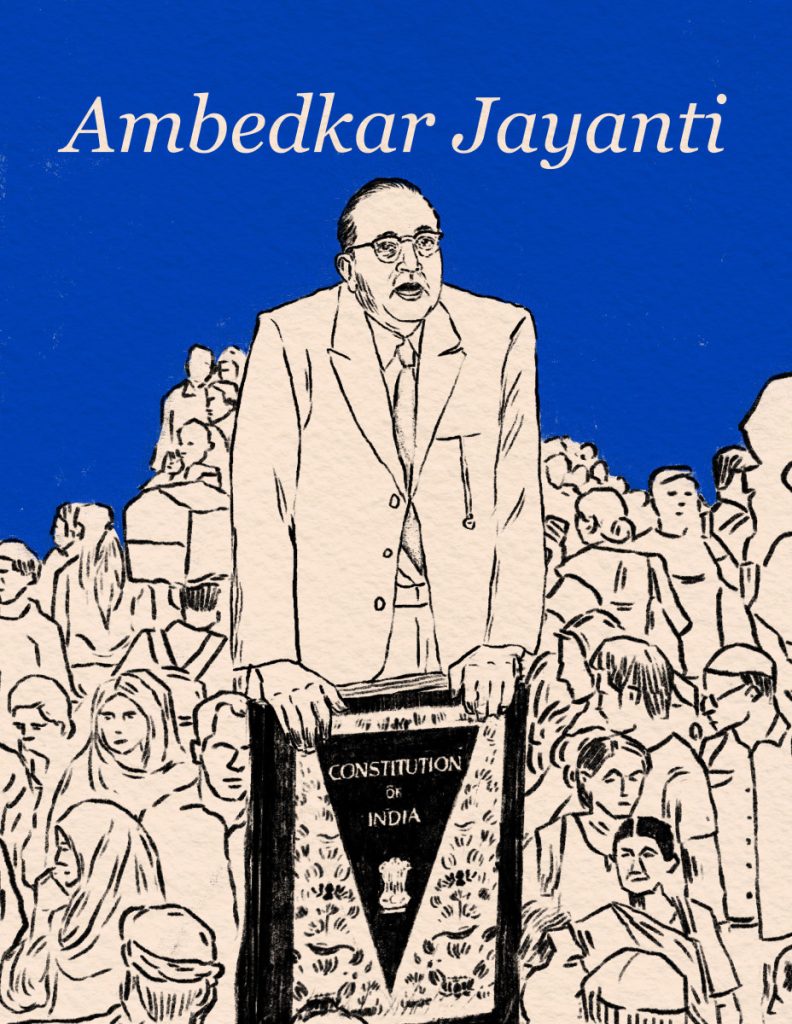

April 14 is Ambedkar Jayanti, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar's birth anniversary.

Ambedkar, today, is everywhere, and yet, he’s nowhere. Quoted, defied, misread, weaponised. Politicians romanticise him without reading his works. But one group that remains conspicuously disengaged from Ambedkar's intellectual legacy is the public policy sector: Professionals who claim they can bring ‘social change’ by learning R, STATA, SPSS, and Python without learning the ‘language’ of the ‘society’.

One seldom asks the most pressing question: Who are we creating, implementing and evaluating these policies for? This article argues that public policy professionals must urgently and meaningfully integrate Ambedkar’s thought to design truly inclusive and effective policies.

One seldom asks the most pressing question: Who are we creating, implementing and evaluating these policies for? This article argues that public policy professionals must urgently and meaningfully integrate Ambedkar’s thought to design truly inclusive and effective policies.

Ambedkar and public policy: A missed opportunity

It is a rather challenging task to identify social and economic issues that Ambedkar hasn’t covered in his writings in the Indian context. From gender to caste to workers’ rights, Ambedkar’s writings range from Castes in India, a sociological work, to Problem of the Untouchables of India, a policy document, making him an expert in social science and policy, probably one of the pioneers of critical policy studies.

It is baffling to realise that after skimming through multiple public policy postgraduate programmes at Indian universities, hardly any offer a course on caste, let alone Ambedkar. Being one of the most interdisciplinary minds of the 20th century, Ambedkar, who extensively wrote about the formation of the caste structure, gender, and its politics, is rarely invoked in public policy education and practice. An economist, lawyer, philosopher, and sociologist, his insights are foundational for anyone working in or around Indian society. He didn’t just theorise structures, he lived and attempted to dismantle them. His method was critical, always questioning power, whether in the form of Gandhi’s moral authority, the British Raj’s legislative frameworks, or the nature of the Indian state.

Engagement with Ambedkar at the public policy level would have three outcomes:

First, an improved understanding of social conflicts in the Indian context – Its origin, nature and mechanism;

Second, an assessment of the foundations of existing policy, including legislative policies;

Third, greater understanding of social theory, elements I believe most policy professionals lack in their training.

Reservation: For economic alleviation or social access

Reservation since the implementation of the recommendations by the Mandal Commission has been a contentious issue. Upper-caste critics are quick to argue that reservations are "anti-merit". Some go further, insisting that caste should be replaced by economic criteria, arguing that caste superiority doesn’t necessarily imply economic privilege. Such arguments reveal a fundamental misunderstanding of the social reality of India.

What's unsettling is that development and public policy professionals tasked with solving inequality in India, from their air-conditioned rooms with their fancy degrees, echo this flawed logic. They conveniently fail to grasp caste as a structure of privilege and punishment.

Ambedkar recounts in his autobiographical work, Waiting for Visa, how he was forced to sit on the floor in school, and how a peon poured him drinking water, without whom, accessing water was a crime. He wrote in his other works extensively about how Brahmanism restricts the mobility and access of the Dalits in the public sphere.

An article published in Nature a couple of years ago claimed how 98% of faculty members at top IITs belong to so-called upper castes, suggesting that the failure of the implementation of reservation policies led to a stark dip in representation. Reservation, then, is not a poverty alleviation tool. It’s a structural correction for historical exclusion.

Labour and Class Analysis

Ambedkar recognised that since most workers are from the so-called lower castes, they are oppressed by both Brahminism, and the capitalist, who in most instances would also be 'upper' caste. The backers of the economic consideration for reservation must pay heed to the caste-class ideas of Ambedkar.

In Evidence Before the Southborough Committee, Ambedkar writes how in the material sense, there is no such thing as a Parsi, Muslim or a Hindu. There are only landlords, capitalists and labourers, implying that class-struggle supersedes religious affinities, a valuable lesson for policy professionals working in the field of labour rights.

Women

Ambedkar draws a similar conclusion in the case of the oppression of women. He deems caste central to the condition of women. The Hindu Code Bill, which he championed, proposed revolutionary ideas: equal property rights, the right to divorce, and an end to polygamy among Hindus. Yet it faced strong opposition, even from the so-called progressive men of the time, like Rajendra Prasad. Why? Because policy-making, then and now, often avoids interrogating the deeper structures, like Brahmanism, that control women’s bodies and autonomy. Ambedkar understood that social reform needed more than lip service. It needed the dismantling of oppressive systems.

The value of Ambedkar in public policy

The larger questions remain.

Should the government (any government led by any party) base its policy-making practice around caste? Did the implementation of the CUET exam format consider that uniformising college admission would lead to the increased reliance of students on coaching institutions that are mostly accessible to communities with purchasing power, ergo, the 'upper' caste? Do policy professionals working on WASH centre the rights of manual scavengers while evaluating the impact of the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan? How many organisations explicitly research caste and its intersection with policy and governance? How are we researching public policies by ignoring the structural issues of more than 70% of the public? Ambedkar humanises public policy, offers us an opportunity to think critically and engage with the reality of the society.

Today, the public policy space in India is becoming increasingly corporate. Big consultancies, slick reports, white papers, and podcasts dominate the ecosystem. While this may be the reality of our times, it doesn’t have to mean the end of critical thought. It’s even more reason to root ourselves in Ambedkar’s intellectual legacy. He reminds us that policy isn’t just about numbers, it’s about people. And to truly serve the public, we must understand the structures that shape their lives.

Ambedkar isn’t just for historians, sociologists, or political theorists. He is essential reading for anyone who hopes to work in or transform Indian society. To Ambedkarise our policy practice is not a symbolic act, it is a political necessity.

Pranav Kishore Saxena is a social scientist and public policy professional.

This article went live on April thirteenth, two thousand twenty five, at twelve minutes past seven in the evening.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.