Mustard Seeds and Elephants: Caste, Corruption, and the Invisible Hand of Reservation

This is a sequel to the essay, Cockroaches in the Creamy Layer and Rebranding of Casteism. It splits the mustard and rides the elephant, and lays bare the profound anxiety that grips the national elite.

Ambedkar captured the psychological essence of the caste system when he described it as an intricately aligned structure: “an ascending scale of reverence and a descending scale of contempt.” This formulation reveals that caste is not merely a rigid hierarchy where power, privilege, and resources are unevenly allocated. It is far more insidious, functioning as a deeply ingrained mental framework as well. At the apex of this system stand those who are deemed worthy of unwavering reverence, while those at the bottom are subjected to relentless scorn and disdain.

To preserve this social order, it is essential to uphold its material and mental components. At the material level, the caste system inherently becomes a policing system, vigilantly guarding against the redistribution of wealth and resources and ensuring that the material world remains unchanged – sanatan, or eternal. But it goes further, it penetrates the depth of the psychic sensorium of individuals, perpetuating itself through generations and ensuring that each new generation internalizes the same rigid structures of reverence and contempt.

The following observation by William Logan, the collector of Malabar, in The Malabar Manual first published in 1887 is an exemplary case: “The Hindu Malayali is not a lover of towns and villages. His austere habits of caste purity and impurity made him in former days flee from places where pollution in the shape of men and women of low caste met him at every corner; and even now the feeling is strong upon him and he loves not to dwell in cities.”

I have rarely encountered a sentence so densely packed with information. It clearly defines who a Malayali is (a Savarna), the Malayali’s gender (male), and touches on what French psychoanalyst Félix Guattari might call the three ecologies – mental, environmental, and social. The Malayali’s mind is closed, his environment is idyllic, and his society is entrenched in casteism.

What the three ecologies can do, and do with impressive efficiency, is reproduce themselves ad infinitum. It is a finely-tuned system that perpetually keeps the “Other” in check – whether that Other is the women inside, the lower castes outside, or the dynamics of the village, the city, or even democratic spaces. Instead of humans crafting a system that aids their survival, we see a system meticulously designing human psyches to ensure its reproduction. This is why Ambedkar often spoke about the mechanics of caste. It operates with clockwork precision, 24x7. The Hindu Malayali – and the Indian Savarna elite through metonymy – isn’t just allergic to pollution in the conventional sense; he’s terrified of social interactions with the lower castes.

In essence, the caste system functions not so much as a democratic space but as a heavily policed state, where the main priority is preserving the eternal sanctity of its rigid social hierarchy – both in terms of material reality and mental conditioning. It is no surprise, then, that Rama, the ruler-par-excellence of caste enforcement, the Maryada Purushottam, Ideal Man-King-God, is such a hit with the die-hard defenders of this cosmic order. After all, he’s the hero who took down both Shambuka, the over-ambitious Sudra who dared defy his caste-bound duties, and Tataka, the “polluting” woman.

The caste system could easily be described as the most advanced self-regulating policing system in history. It turns everyone into a de facto policeman, constantly on duty. Your primary task? To keep a vigilant eye on anyone below you, making sure they don’t step out of line, while dutifully saluting anyone above you. In this finely tuned social hierarchy, the power structure is self-enforcing.

Any attempt to disrupt this delicate balance, whether by altering the material conditions or challenging the mental framework of caste, must be swiftly and severely punished. In this system, you’re not just living within the hierarchy; you’re actively maintaining it – guarding the gates of the social order, whether you’re at the top or somewhere in the middle.

The philosophy of this tightly guarded caste state can be summed up as: the superior can take it all, while the inferior must be denied everything. It is a system designed to ensure that those at the top enjoy unchecked privilege, while those at the bottom are systematically stripped of rights, opportunities, and dignity. In this social order, keeping the balance means hoarding power and resources for the few, while enforcing deprivation for the many.

From inside this system, it might seem sanatan, eternal, divine, as unchangeable as the cosmos itself, simply because you’re too close to see that it is a man-made contraption. Instead of viewing the system from various angles and grasping its temporal and mechanical nature, someone trapped within it becomes obsessively fixated on the behavior of their inferiors, blissfully ignoring the antics of their superiors. All their mental and physical energy is devoted to supervising those below them, anxiously guarding against any sign of rebellion or encroachment. Meanwhile, this built-in feature of the eternal psyche allows gods, prime ministers, and film stars to indulge in the kind of morally dubious behaviour you’d never tolerate from your own inferior neighbour. A Malayalam proverb captures the governing logic of the caste machine: “You won’t notice the elephant vanishing, but you’ll spot a mustard seed disappearing.” (Kaduku chorunnathe kanoo, ana chorunnathu kanilla.)

While the elephant is led away

Referring to the coup d’état of Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte (later Napoleon III) on 2 December 1851, Marx crafted a sexist equation typical of the time: “Nations and women are not forgiven the unguarded hour in which the first adventurer who came along could violate them.” In the Indian context, it wasn’t merely the unguarded hour, or a lapse in vigilance, that allowed foreign adventurers to succeed. Rather, it was the misdirected guarding – an obsessive focus on trivial matters, like fretting over mustard seeds – while the elephant was quietly being led away.

So, if a sage-like Savarna guru, with an air of wisdom and a beard as grand as his proclamations (think Golwalkar), advised his disciples not to waste energy fighting the British, it was perfectly logical in their worldview. They were to fix their attentions elsewhere. After all, in their eyes, losing even an inch to the lower-caste Other was an unforgivable crime. Surrendering the entire plot to a European – who was taller, fairer, and more technologically advanced – was a minor inconvenience, easily overlooked.

The “superior takes it all” logic didn’t stop at wealth and material possessions – it extended far beyond, even creeping into the realm of sexuality among the Savarna in Kerala a century ago. In fact, it could be argued that Savarna women of that time were viewed as little more than property themselves, subject to the same rules of ownership and control. Their bodies, like land or wealth, were just another asset (as in Marx’s quoted statement) in the hierarchy of power – claimed and dominated by those at the top.

Among the Namboothiri Brahmins, only the eldest male (the superior) was granted the privilege of marrying within his caste, leading to a quaintly archaic polygamous system where an elderly man with multiple wives might still marry a teenage Namboothiri girl. Meanwhile, other Brahmin men – his younger brothers, the inferiors at home who are still deemed superior to the Sudra men of the servile Nair caste – were graciously allowed to engage in concubinage with Sudra women. But heaven forbid a Savarna woman (both from Namboothiri and Nair castes) should fall in love with a non-Savarna male! In such cases, she was swiftly excommunicated – a fate worse than hell in the caste universe – leaving her in a casteless limbo.

To put the caste machine in the terms of Lacanian psychoanalysis, when individuals gaze “up” at their superiors, their reflection is minimised, portraying them as “nothing” and reinforcing a sense of inferiority. Conversely, when they look “down” at those deemed inferior, their reflection is magnified, making them feel as “something” and solidifying their status within the hierarchy.

Unlike in democracies, where mirroring occurs horizontally among equals, in a caste society, this process is vertical. The self oscillates between “nothing” and “something” depending on one’s position in the social pyramid. At the apex, the Brahmin caste, which aligns its consciousness with the cosmos (aham brahmasmi), encounters no sense of “nothing” except as a cosmic void – a profound negation that negates negation itself. In contrast, at the base, the untouchable/ unseeable/ unkissable/ unsmellable/ unhearable castes, deprived of a sense of “something”, confront a stark negation of the self, the void itself becomes its dwelling.

This vertical mirroring perpetuates a cycle of dominance and subordination, creating a self-concept markedly different from the more egalitarian self-perception found in democratic societies. Philosophically, this extreme polarity between the Brahminic and Untouchable castes can be framed as the binary of Brahminic philosophy – sat, chit, ananda (existence, consciousness, bliss) – versus the Buddhist philosophy of asat, anatta, dukkha (non-existence, non-self, suffering).

Whenever the mechanisms of caste are challenged, the Savarna is gripped by a profound anxiety.

British colonialism, with its bourgeois ideals, struck a devastating blow to the caste universe, generating a wave of anxiety among the Savarna. The once idyllic environmental and social landscapes of this universe were destabilised – perfectly encapsulating Marx and Engels’s observation that “The bourgeoisie, wherever it has got the upper hand, has put an end to all feudal, patriarchal, idyllic relations. It has pitilessly torn asunder the motley feudal ties that bound man to his ‘natural superiors,’ and has left remaining no other nexus between man and man than naked self-interest, than callous ‘cash payment’.”

Under bourgeois pressures, the Savarna material world and mindset were destabilised. The closed mind of the caste Hindu, once comfortably insulated, began to be colonised by the very Others he had long kept at a distance: the woman, the low-born, the city, democratic ideals – all began to wreak havoc within his psyche.

When Nandy counted the lost mustard seeds

In a certain stream of postcolonial thought, this unsettling of traditional mental ecologies is framed as the ultimate betrayal – the internalisation of the enemy. Ashis Nandy, with a gaze toward the past, calls this process the “loss of self,” where the colonised adopts the coloniser’s values, ideologies, and practices, slowly losing his own identity. In a way, Nandy is absolutely right, though perhaps not in the way he intended. The enemy was never just an external force; it was always lurking within, too close for comfort.

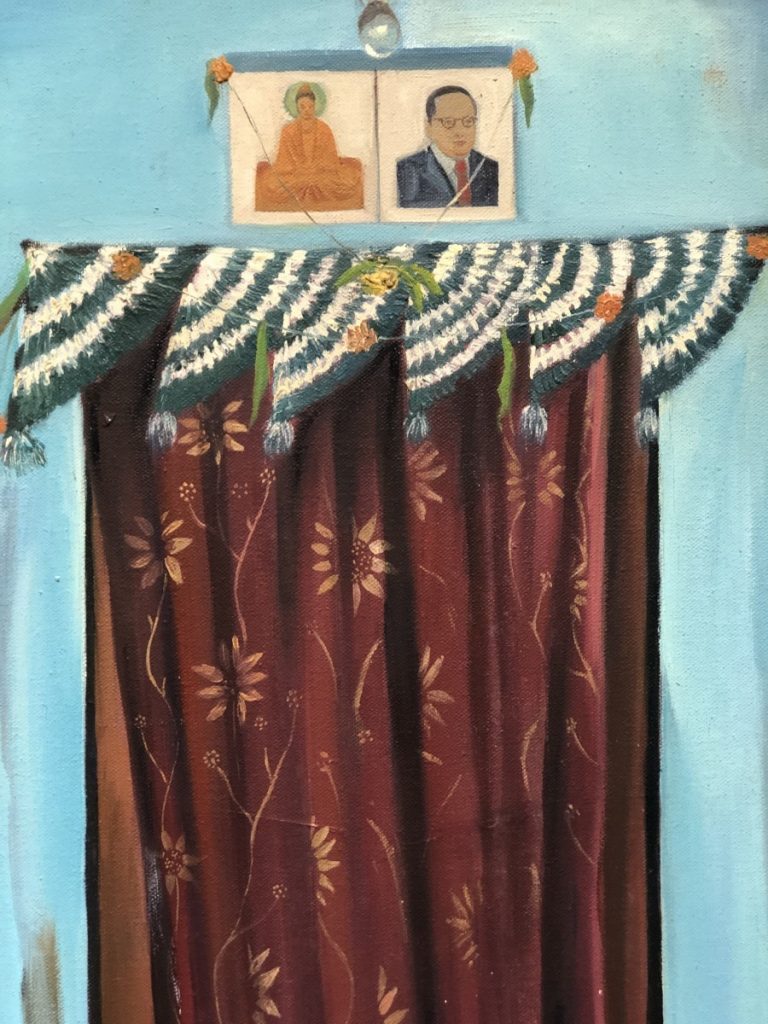

Vikrant Bhise's 'HOME WALL, 2023, oil on canvas. Photo: S Anand, from the exhibition Sense and Sensibilities: A Reflective Realisation.

An Avarna, a Mahar, receiving an international education (Ambedkar), an Ezhava attaining sanyasahood (Narayana Guru), yet another Avarna, a Pulaya parading his newfound freedom on a bullock cart in a cloth historically denied to him (Ayyankali) – these acts were not just rebellions; they were signals that the carefully constructed mental and physical barriers of caste had started to crumble. The enemy had breached the walls, and it wasn’t the coloniser – it was those who had long been pushed to the margins, now stepping into spaces that had always been off-limits. The enemy, it turns out, was far too close, and far too deadly!

The effort to return the so-called enemy to their former, “rightful” place has been christened with a fashionable term in postcolonial theory: the “recovery of self.” In Ashis Nandy’s world, two figures embody this nostalgic revolutionary politics – Gandhi and Aurobindo. Now, whether Gandhi or Aurobindo ever truly succeeded in restoring that lost, authentic Indian self by banishing the West’s influence is up for debate. But when it comes to this project of recovering the lost self, Nandy himself holds a special place in my heart. After all, his infamous 2013 statement suggests that he may have achieved a sort of mystical union with that sanatan self – one obsessively preoccupied with what the lower caste “Other” might take away:

“It will be a very undignified and – how should I put it – almost vulgar statement on my part. It is a FACT that most of the corrupt come from the O.B.C.s and the scheduled caste and now increasingly the scheduled tribes. And as long as this is the case, the Indian republic will survive.”

Ah, paternalism at its finest! But what exactly was he getting at? I’m still scratching my head on this. Perhaps he meant that since Dalits and OBCs are relatively new to the game of corruption, they’re entitled to indulge a little longer until the Savarnas catch up and the playing field is even. Or maybe he was hinting that in the murky waters of corruption, visibility flips the usual social script: the upper castes slip into the shadows, while the historically invisible castes become glaringly obvious. Either way, it’s a head-scratcher for mere mortals.

While the “recovered self” might navigate such cognitive heights with ease, we, who are stuck in the ordinary realms of logic, have to rely on simpler tools – like the good old Freudian “parapraxis” or slip of the tongue. Freud tells us that these verbal slips aren’t accidental; they are the repressed thoughts bubbling up to the surface, exposing unresolved anxieties.

So, when a postcolonial thinker of repute presents his “facts” on corruption without any facts to back them up, what we’re seeing is not a statement of fact but a Freudian slip. It’s a classic moment where the typical Savarna mind – rooted in sanatan fears – lets its guard down and reveals its deeper preoccupation: the dread that the Avarna, the marginalised, might actually accumulate wealth and power. In this fleeting moment, the mask slips, and the eternal worry of the sanatan soul is laid bare for all to see.

Why do I say that his so-called “facts” on corruption are anything but factual? Two reasons. The first is ontological. Corruption, by its very nature, is a shadowy affair, cloaked in secrecy. A truly successful act of corruption, by definition, remains invisible. We only ever hear about the bungled attempts – the ones that get caught. Basing judgments on these slip-ups is like trying to measure an iceberg by what’s above the water. The real bulk, the successful corruption, is forever submerged, never surfacing for empirical scrutiny.

So how can we possibly compare the corruptions of Savarnas and Avarnas when the truly successful cases are, by nature, impossible to detect?

If we were to take Nandy’s statement seriously, it would ironically be for the opposite reason: We notice, as Nandy does, more cases of corruption involving Avarna individuals precisely because they haven’t yet mastered the art of being corrupt. They’re getting caught! They’re not just losing at corruption – they’re losing socially too.

The second reason is quite common: There is hardly any empirical study backing up Nandy’s claim. His statement reeks of Savarna bias – it’s like counting mustard seeds while elephants are being carted away by the Savarna. In other words, while Nandy focuses on minor cases of corruption, the real heavyweights of financial wrongdoing are busy with their grand schemes. Kleptocracy and crony capitalism have systematically siphoned off vast amounts of money, with powerful elites creating an intricate web of institutionalised corruption. This complex system of favouritism and deceit ensures that the biggest players remain untouchable, while the smaller infractions are scrutinised. But the habitual, dating back to the days of Manu, forces Nandy to focus on trivial cases, leaving the true giants of corruption to operate in the shadows, manipulating the system to their advantage.

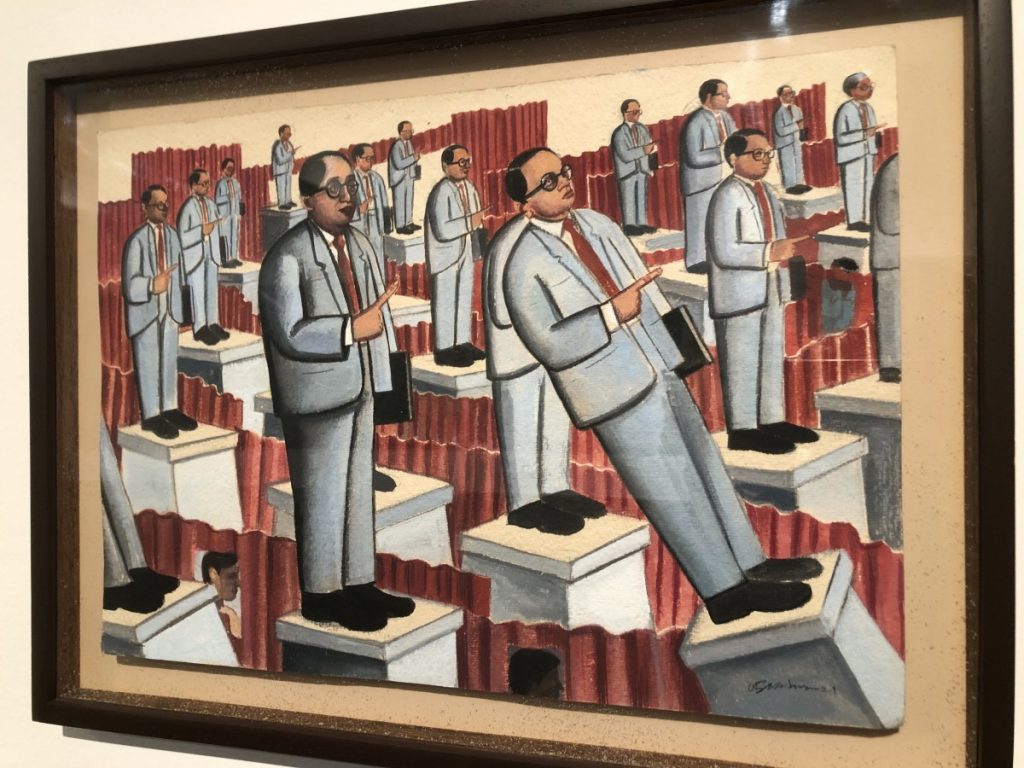

Vikrant Bhise's 'Height of Capitalism', 2021,

acrylic and watercolour on paper. Photo: S Anand, from the exhibition Sense and Sensibilities: A Reflective Realisation.

The poverty of facts

This ancient ritual of counting the mustard, ensuring the low-born remains in place, can also be seen working in the Supreme Court’s EWS verdict allowing educational and employment reservations for the Economically Weaker Section of the Savarna. The judgment reads: “Without economic emancipation, liberty – indeed equality, are mere platitudes, empty promises tied to “ropes of sand”. The break from the past – which was rooted on elimination of caste-based social discrimination, in affirmative action – to now include affirmative action based on deprivation, through the impugned amendment, therefore, does not alter, destroy or damage the basic structure of the Constitution. It adds a new dimension to the Constitutional project of uplifting the poorest segments of society” (p.67). I find this statement unconvincing because it, as with Nandy’s claims, does not correspond to facts.

According to the Union Budget 2024–25, the establishment expenditure of the Government of India stands at Rs 7.82 trillion (Rs 7,817,740,000,000 or approximately $ 94.1 billion). This includes salaries, wages, allowances, and pensions of central government employees and pensioners. The total budgeted expenditure for the financial year 2023–24 is Rs 44.91 trillion (Rs 44,91,486,000,000,000 or approximately $ 540.5 billion).

On page 38 of the Annual Report on Pay and Allowances, it is reported that the number of employees under the Government of India is 31,15,343, out of a total sanctioned strength of 41,11,146, leaving 24.22% of posts vacant. Additionally, the Ministry of Personnel, Public Grievances & Pensions noted in 2022 that the total number of pensioners under the Government of India stands at 69,76,240. Using this slightly older data, the combined total of employees and pensioners is 10,091,583. This is the number of people the Rs 7.82 trillion ($ 94.1 billion) was meant to support.

When you crunch the numbers, this expenditure results in an average of Rs 774,679.33 (approximately $ 9,333.70) per person per year, which equates to approximately Rs 64,556.61 (approximately $ 778) per month. Now, here’s the twist: this average figure is still below the upper limit of Rs 8 lakh (approximately $9,633) that classifies one as “poor” as per the EWS scheme. Even more intriguing is the fact that this average includes both salaries and pensions. Given the wide income disparity between Class A officers and Class D employees, and the typically lower pension amounts, the real incomes of many could be significantly lower.

The inequality in income distribution among different classes of employees in the government is stark. Top-tier officers likely earn much more than the calculated average, while those at the lower end – especially pensioners – earn far less. And let’s not forget, a chunk of this money will find its way back to the government coffers through income tax, especially from higher earners.

And yet, the Supreme Court staunchly believes that EWS reservations in employment will elevate the poor among the forward communities. A measure that, on average, won’t even help you clear the poverty line is now heralded as a solution for upliftment! If staying beneath the poverty line counts as upliftment, we’ve surely entered the world of mathematical whimsy. But if there’s any mathematics involved here, it’s more like the Mobius strip. At first glance, you’d think it has two sides – one for those below the poverty line, and another for those above. But as you trace the curve, you’re in for a surprise – it’s a one-sided loop, and somehow, you are always on the below-poverty side.

In short, the factual basis of the judgment reminds me of a joke about my favourite philosopher, G.W.F. Hegel. One day, Hegel was delivering a lecture, soaring high on the wings of speculative rigor. A skeptical student, unconvinced, interrupted and said, “Herr Professor, your theory doesn’t match the facts.” Unruffled, Hegel calmly replied, “So much the worse for facts.”

Ah, the Owl of Minerva, soaring gracefully over the stubborn realities of the world below!

The Supreme Court’s ruling, purportedly aimed at uplifting the financially disadvantaged, seems more like a spectacle of distraction than a genuine remedy. Much like Noam Chomsky’s critique of media’s role in diverting attention to trivialities, this modest offering of reservation, in the context of economic upliftment, is wielded by corporate elites and media houses as a clever sleight of hand. It keeps our gaze fixed on a token solution while obscuring the deeper financial issues that truly matter. It’s a strategy, not for solving poverty, but for keeping the real conversation conveniently out of reach.

The moksha of reservation and the itch you can scratch

Once upon a time, in a society not too different from ours, salvation – or moksha – was the go-to remedy for all earthly woes. It diverted attention from all earthly problems. “Feeling a bit peckish? Don’t worry, moksha will sort you out in the afterlife!” Meanwhile, a tiny elite indulged in the luxury of palatial estates and lavish feasts, with the divine promise of eternal peace conveniently postponed.

But lo and behold, the times they are a-changin’. No longer must you bide your time in mortal misery, waiting for an afterlife miracle. Enter stage left: the modern-day avatar of moksha – reservations! Yes, reservations are here to whisk you away from your earthly trials and tribulations, no waiting required.

Economic hardship? Confirmed! Personal suffering? Absolutely! Just apply for a reservation post, and your problems are supposedly resolved with the ease of a quick fix. Sit back and embrace the new-age solution. After all, who needs an afterlife when you’ve got reservations offering instant remedy, right here and now?

So, what’s my quarrel with “distributive justice” and “substantive equality” – the darlings of modern legal discourse? None, really. In fact, I’m all for both – principles as sound as any. But here’s my gripe: it’s not the principles, but the way they’re executed, steeped in casteist practices. Let us get to the heart of it: Is real justice and substantive equality about splitting a mustard seed into a million microscopic pieces, or perhaps chopping an elephant into similarly tiny bits? Our lawmakers and legal scholars seem convinced it’s the mustard seed strategy—believing that a fine division of scarce resources will somehow, miraculously, bring about a just society. I don’t know about you, but my common sense doesn’t quite buy it.

Here’s my question: where exactly do we begin redistribution – from the top or the bottom? Why not start at the top and let the “trickle-down effect” (ah yes, that enchanting mantra of neo-liberal economists and financial institutions) work its magic? Picture it: justice and redistribution cascading gracefully down the social ladder, like a benevolent waterfall, soaking every layer of society!

But that is precisely what the Sanatan mind chooses not to see. A Sanatan mind is far more unsettled by the sight of an Avarna building a modest 1500-square-foot house with a bank loan, which he’ll likely be repaying for the rest of his life than by the grotesque extravagance of a Baniya billionaire blowing billions to create a mansion in Mumbai. Luxury excess? No problem. But upward mobility with a mortgage? Now that’s a real eyesore!

Instead of offering a mental pat on the back, thinking, “Well, despite all the social odds, he (the Avarna) actually made it,” the sanatan mind slips into its ritualistic mode of safeguarding the sacred hierarchy: “How on earth did he pull that off?” Forget admiration – the real priority is to figure out how the structure was breached!

Ambedkar dissected the sanatan mind with surgical precision when he wrote:

“Mr. Gandhi does not wish to hurt the propertied class. He is even opposed to a campaign against them. He has no passion for economic equality. Referring to the propertied class Mr. Gandhi said quite recently that he does not wish to destroy the hen that lays the golden egg. His solution for the economic conflict between the owners and workers, between the rich and the poor, between landlords and tenants and between the employers and the employees is very simple. The owners need not deprive themselves of their property. All that they need do is to declare themselves Trustees for the poor. Of course, the Trust is to be a voluntary one carrying only a spiritual obligation.” (Italics mine)

Our true tragedy isn’t reservations; it’s the enduring presence in power – whether in parliaments, legislatures, or courts – of those who echo Gandhi’s reluctance to pursue economic equality and shy away from challenging the propertied class. If they were genuinely committed to justice, they wouldn’t dress up the current reservations in catchwords like “upliftment,” “substantive equality,” or “distributive justice.” Instead, they’d champion concrete solutions: genuine progressive taxes (not the current indirect taxes and a flat rate above Rs 30 lakhs, which again align with the “the superior takes it all, the inferior is denied everything” logic), wealth taxes (instead of the current income tax), universal basic income, and land reforms. They’d focus on expanding social safety nets, investing in public services, enforcing minimum wage laws, and promoting employee ownership.

But for that, you need genuine individuals – those with a real passion for justice and equality, who are truly empathetic to the dispossessed others. Not the kind of people who are merely lining up for power, positions, and post-retirement sinecures.

Until then, when you’re tempted to blame reservations for all our problems, remember: someone’s playing tricks with your mind and distracting you from the real issues – while a crony quietly walks away with the elephant.

Post Script: Speaking of soaring minds, let me end with an anecdote about one of India’s greatest writers, Vaikom Muhammad Basheer. When asked about his idea of paradise, Basheer’s answer was delightfully unexpected: “It’s when you scratch a fungal infection.” The shrewd psychologist in Basheer knew that that’s the only moment a casteist society might forget its obsessive concern with the “inferior” Other and focus on its own business. Heaven, indeed!

Anilkumar Payyappilly Vijayan is a poet and an Associate Professor of English at Government Arts and Science College, Pathiripala, Palakkad. Under the sign A/nil, he is the author of The Absent Color: Poems.

This article went live on September fifteenth, two thousand twenty four, at zero minutes past nine in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.