The Supreme Court's Question About Reservations Is the Wrong One to Ask

"For how many generations will reservations continue?"

The five-judge bench that is meant to examine whether the 13% Maratha reservation is valid or not, will also examine the 50% cap on reservations the Mandal Commission judgment.

This question only indicates that the Indian judiciary – in its present mode of thinking – is suspicious of the positive role of reservations in changing the caste-cultural inequality.

But so far, no Supreme Court judge has asked, “For how many generations will caste inequality continue?" from a sitting bench.

Let us see the conditions of Shudras or OBCs in places where reservations were treated as anti-meritocracy and also as going against socialist equality, for instance in Bengal.

Bengal in general and West Bengal after Partition, in particular, produced several leading intellectuals of India. Three castes –Brahmins, Kayasthas and Baidyas – were the most educated, giving rise to what is known as the Bengal Renaissance.

In the process of their nationalist renaissance, they designated themselves as ‘bhadralok’ (great and gentle people). The rest of the Shudras and Nama Shudras were designated ‘chotolok' (or 'chotalok’, small or low people, meaning 'lower' or 'mean' castes). This division of 'bhadra' and 'choto' further adds to the humiliation and oppression of the caste system, but the Bengal Brahminic renaissance accepted it as normal.

When Tamil Nadu initiated the reservation battle, the Bengali bhadralok intellectuals saw that as anti-modernist and anti-merit. No anti-Brahmin consciousness was allowed to emerge from Bengal. The Bengali bhadralok of all ideologies (that state was mainly divided into liberal and communist) hated the reservation ideology coming from the South.

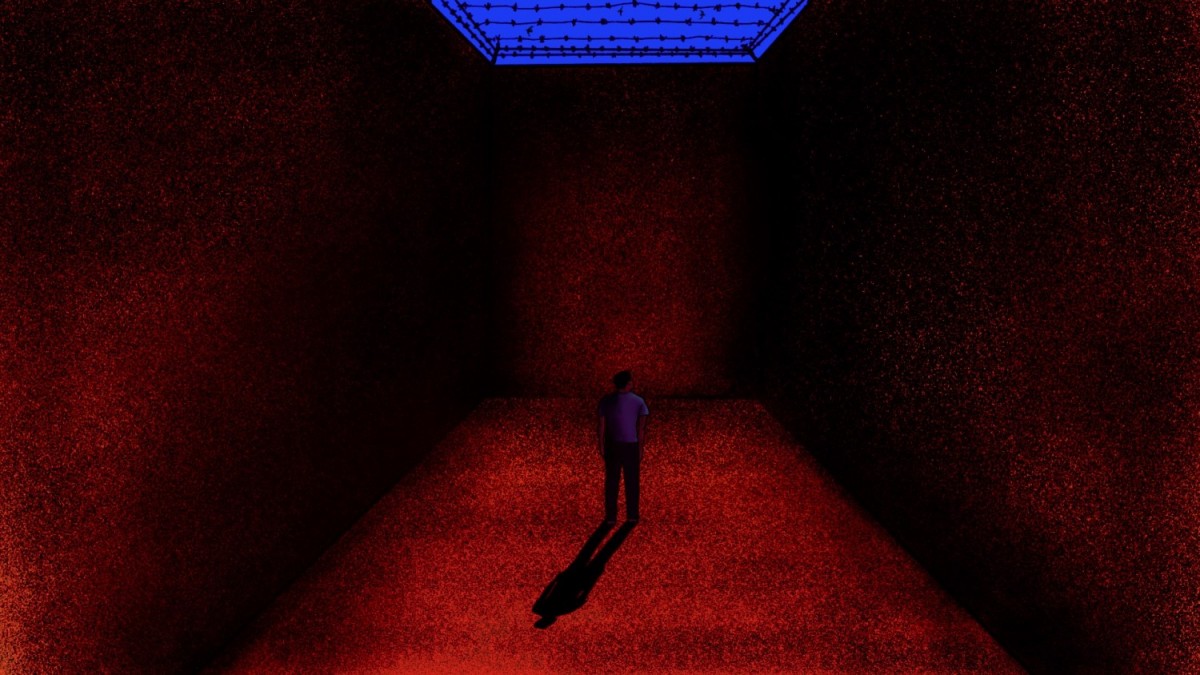

Illustration: Pariplab Chakraborty

The chotolok never told the bhadralok that they, who were historically assigned the job of doing agriculture and artisanal tasks needed reservation in education and employment. The bhadralok, even now, does not put a hand to the plough. The bhadraloks' socialist and liberal ideologies did not change the caste-based work division.

The Bengali bhadralok was among the most educated in Sanskrit and Persian (during the Muslim rule) by the time British arrived in India. After the Raj was established by the English, they were the earliest English-educated Indians, starting with Raja Rammohan Roy. They were also first to cross the seas violating the Brahmin dictum never to doit. Roy was perhaps the first modern Brahmin to die in England.

Also read: West Bengal’s Landscape Is Shifting from ‘Party Society’ to ‘Caste Politics’

No chotolok man or woman could become the chief minister of Bengal so far.

Bengal is the state which has given the least number of reserved jobs to Shudras, OBCs, SCs, STs following its own cardinal principle that reservations will destroy the sacrosanct 'Bengali merit'.

The Mahishya community, which is the largest Shudra agrarian group, is for reservations and is tilting towards the BJP. The party has made a Shudra, Dilip Ghosh, the state party president and chief ministerial candidate.

Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu

Against Bengal, the Maharashtra experiment shows a different way. In that too the Brahmins, Banias but also Shudras and Ati-Shudras got early English education and produced the likes of Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Gopal Krishna Gokhale, V.D. Savarkar and also Mahatma Jyothirao and Savitribai Phule.

Bal Gangadhar Tilak. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

There was also an early reservation and preferential treatment demand for Shudras and Ati-Shudras.

Chattrapati Shahu Maharaj, the ruler of Kolhapur, initiated the early reservation process which helped B.R. Ambedkar emerged from the Dalit community to give voice to multi-caste ambition. Today, the Marathas who were not for reservation in 1990 see the need for it. Now even Shahu Maharaj's grandchildren are demanding it. A strong middle class and educationally ambitious social force has risen from all castes in Maharashtra because of reservation and others want to be part of it.

Similarly the Tamil Nadu experiment with reservations has improved the conditions of all castes. The Brahmins and Chettiars who are outside the reservation ambit did not get pushed down to the labour markets. They invented new ways of living a better life.

The Indian judiciary must see reservation in the light of the successful Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu mode of accommodation and diversification in every field of life by all castes and communities. On the other hand, West Bengal is a negative example of social stagnation because of lack of a drive towards reservation and educational motivation.

In a stagnant state, without much middle class formation among Nama Shudras and Shudras, the BJP seems to be attracting the Shudras and OBCs. The left-liberal ‘no caste in Bengal' theory is seen as a most regressive ideological step.

BJP supporters during Prime Minister Narendra Modis public meeting ahead of West Bengal Assembly Polls, at Brigade Parade Ground in Kolkata, Sunday, March 7, 2021. Photo: PTI/Swapan Mahapatra

The anti-identity politics of this bhadralok stream of thought is now paying a heavy price. Reserved candidates in every institution have brought the identity of community and its social status into focus and that played a transforming role. But the left-liberals of Bengal missed Ambedkar's bus and were busy studying Marx and Tagore.

The left bhadralok intellectuals held a strong view that reservations will undo socialist and democratic equal opportunities for all.

But no chotolok was allowed to think about the very fact that they were called “chotolok" which is insulting and dehumanising. Such a status does not allow the chotolok to sit with the bhadralok in any institution. The English-educated chotolok men and women less in number compared to Bengali bhadralok intellectual in any major central university or IIT and IIM.

Jyoti Basu famously said, "There is no caste in Bengal" when the question of implementation of the Mandal reservation arose. We do not see a single visible OBC leader or intellectual on the national map from that state.

Bengal hardly has an equal, competing, educated middle

Now the rightwing bhadralok of India joins the chorus of the left bhadralok and asks for how many generations the chotolok of India will enjoy reservations.

Also read: At IITs, PhD Applicants from Marginalised Communities Have Much Lower Acceptance Rate

But they do not ask for how many generations the chotolok should till the land and feed the bhadralok without being equal in any field of modern, capitalist India. They do not ask for how long the bhadralok will keep away from production of food and teach theories of merit outside that domain. Or why colleges and universities do not talk about the merit of production, and just marks in the exam.

The Indian judiciary's mindset comes from this bhadralok view of education, employment and caste blindness.

A view of the School of Physical Sciences building, JNU. Photo: JNU

The Indian Supreme Court never asks how many Jats, Kurmis and Yadavs, leave alone the artisanal listed OBC communities, who till the lands around Delhi, have became professors in JNU, Delhi University, the IITs, and IIMs. How many top bureaucrats from those communities are sitting in the central secretariat?

It is on the Jat lands of Haryana that the top private universities like Ashoka, Amity and OP Jindal exist. How many of their children are sitting in the classrooms of those universities?

In fact their youth, for many generations, were driving bullock ploughs and tractors. How many bhadralok children in and around Delhi till the land for food production?

This is where the social justice angle in judiciary matters.

If bhadralok judges do not feel for the chotolok as much as the white judges in America feel for the blacks, India will crack. The questions that the judiciary asks plays a very critical role in shaping the consciousness of educated Indians. An anti-social justice question from a court bench will be perceived as the eventual judgment in the making.

The question ‘for how many generations will reservations continue’ is exactly like the question, ‘for how many years will Muslim appeasement continue’. The merit theory of the bhadralok does not appear to treat the Shudra, Dalit and Adivasi as an Indian. And this despite their deep roots in this soil which date back to ancient times.

Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd is political theorist, social activist. His latest book is The Shudras: Vision For a New Path, co-edited with Karthik Raja Karuppusamy.

This article went live on March twenty-seventh, two thousand twenty one, at zero minutes past seven in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.