What Dr. B.R. Ambedkar Meant by Manus and Manuski

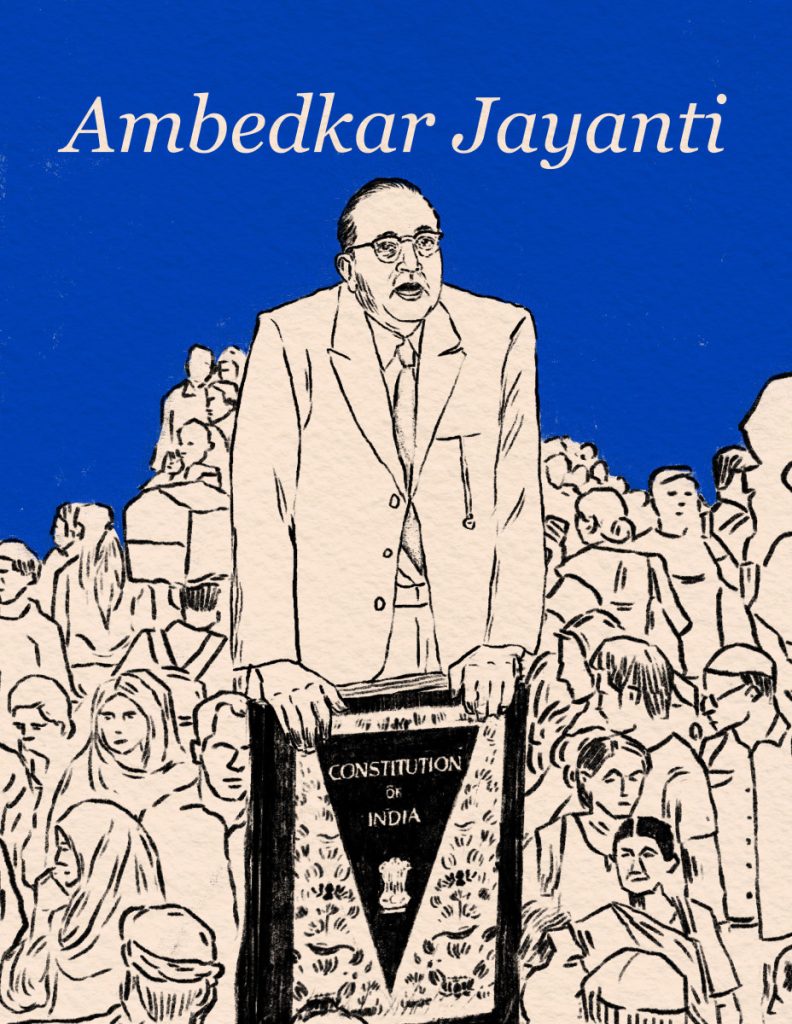

Today, April 14, is Ambedkar Jayanti, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar's birth anniversary.

In his address to the Mumbai Province Bahishkrut Parishad ('conference of the boycotted'), held in Belgao district on April 11, 1925, Dr B.R. Ambedkar argued with Dalits, “Only if you fight intensively you will regain your manuski [human dignity],” that is, be regarded as human in society.

Time and again, Ambedkar asked the Untouchables: “Do you want sukh [comfort, enjoyment] or manuski (Bahishkrut Bharat, February 3, 1928)?” Dignified humanity and personhood along with political representation were most important for stigmatised and subjugated Dalits, propelling them to reform humanism from their denigrated social location.

Time and again, Ambedkar asked the Untouchables: “Do you want sukh [comfort, enjoyment] or manuski (Bahishkrut Bharat, February 3, 1928)?” Dignified humanity and personhood along with political representation were most important for stigmatised and subjugated Dalits, propelling them to reform humanism from their denigrated social location.

Ambedkar argued for Dalits' need of recognition, rights, and redress through proportional representation in the electoral bodies of late colonial India. He provided the ideology and the leadership to politicise the ways Dalits would redefine and reconstitute their relations with the whole of Indian society.

To Ambedkar, Hinduism based on hierarchies of the human could not provide a civil society of equality and dignity, centred on the manus (human). As a result, certainly, to recuperate manuski, caste itself had to be literally broken down, as Ambedkar argued in his famous and undelivered May 1936 speech, Annihilation of Caste. Hinduism could not offer manuski to Dalits. Concomitantly, annihilation of caste is annihilating conditions under which manuski is inscribed for touchables and not for Untouchables. What could Ambedkar and Dalit women and men do to inculcate manuski? They robustly worked on a multi-pronged strategy – social, educational, political, legal, and religious – to regenerate Dalits and not merely reform them like in the case of elite touchable reformers. They focused on both external and internal changes to cultivate manuski.

Ambedkar and Manuski: Towards new self-respect and self-making

The English word humanity does not correspond to a single word in Dalit lexicon. Manuski summarises a constellation of vernacular Marathi concepts: Nitimatta/Naitikta (morals/ethics), Svabhiman (self-respect), Svavalamban (self-dependence), Shila (good character or disposition), Ijjat (dignity), Mansikta (abilities of the mind), and Abru (honour) that were important to building dignified humanity for Dalits.

Ambedkar constituted a new Dalit woman through these inner resources and interrelated ideas of an intrinsically caring and civilised humanity. Dalits used vernacular concepts to connect with universal, global humanity and humanitarianism to recuperate their personhood and humanism on their own terms. Dalits infused humanism with new knowledges and understandings and yet, their moral sensibility is absent in touchables’ concept of humanism. Insensitive to Dalit manuski, the touchables’ dominant world marginalised Dalit ways of being human. As a result, touchables excluded Dalits from becoming fully human. The moralities of the dominant and dominated were distinctly different. Nevertheless, they could be bridged.

Also read: What B.R. Ambedkar Thought of the Word 'Dalit'

To Ambedkar, historically, the larger Indian society denied manuski to Dalits. The caste mechanism restricted Dalits claims to personhood as Dalit humanity itself was constituted as a state of injury and punishment. The consequences were particularly dangerous for Dalit women lacking even minimal security. I am departing from conventions of liberal cosmopolitan humanism and modern humanitarianism that excluded Dalits in the first place. Dalit humanism is “not a liberal humanism of tolerance, but a radical humanism of assertion,” writes Subramanian Shankar in Flesh and Fish Blood. As such, it does not have the luxury of cosmopolitan humanism that asserts “we are all human” or “all lives matter” as in the context of Black Lives Matter moment in the US. Rather, it is a tolerant, expansive, and assertive humanism that insists on accepting Dalits as humans “just the way [they are],” as Shankar puts it.

Further, instead of depending on touchables' gradual reformative work and the change of touchable Hindu hearts, Ambedkar wanted Dalits to be self-reliant, fight caste structures, and work towards their own emancipation. As a result, in Bahiskrut Bharat on March 29, 1929, he thundered, “We ourselves have to fight our untouchable status.”

He was certainly aware of dominant caste prejudice and presumptions and as a result, reminded Untouchables in Janata on March 7, 1936, “Even if you fight for simple manuski, touchables oppose you aggressively. Do away with your vulnerability and weaknesses.” In this manner, although Ambedkar drew upon the liberal tradition of humanism, he also departed to create a unique Dalit manuski.

By the 1920s, Ambedkar viewed Dalit women as makers of manuski and agents of social transformation for the entire Dalit community. Dalit women and issues of gender and sexuality were fundamental to Ambedkar’s manuski. Manuski was most important for stigmatised Dalit women to carve out a space for them in the larger nation, samaj, and family. It would eventually end their otherness and grant them citizenship in modern India. Dalit women deployed a robust body politics and morality of svabhimaan, svavalamban, and manuski to repossess their bodies, become independent, and critically refashion themselves. Ambedkar reinforced Dalit women’s agency to fight their stigma and assert themselves through different strategies.

Education and employment were central to the fight for social transformation. Ambedkar also focused on a robust body politics of comportment to transform Dalit woman’s personhood. Spirituality and religion also provided spaces of caste and gender critique, freedom, and reinvigorated manuski. For example, on the day of dhammadiksha (conversion to Buddhism) October 14, 1956, Ambedkar underlined a completely new life, full of liberty, equality, fraternity, and most importantly gender equality. Through Buddhism, Dalit women encompassed internal and external changes – they asserted their equality as human beings with regards to touchables as well as Dalit men, emphasised self-reliance by “being their own light” (per Buddhist principles), and critically engaged in community improvement and political mobility.

Also read: What Dalit People Taught Us About Education and Why We Must Commit to It

These practices enabled Dalit women to inculcate self-respect, fight for equality and change, and deepen Dalit womanism-humanism. Realising individual manuski was also linked to collective samaj identity. From the 1920s, Ambedkar deployed a multi-pronged strategy on different fronts – social, political, ideological, educational, and scales, internal and external – to build a Dalit samaj and Dalit power on a national scale. Disillusioned with Hinduism, with touchable reformers, and with the lack of recognition for Dalit manus and manuski achieved by a politics of conciliation, Ambedkar encouraged Dalits to be wary of the sociality of caste and recognise their own capacity to be agents of change.

In post-Ambedkar times, Dalits attacked the interlocking technologies of caste, gender, and sexuality by resorting to a politics of writing, activism, and most recently scholarship. In the wake of the Dalit literature of the 1960s, many Dalit women have expressed and published their ideas and life histories to recuperate their manuski, express their suffering, and carve out a space for themselves. In her autobiography published in 1995, the renowned Dalit intellectual Kumud Pawde argued, “Am I not manus (human)? Why did Hindus never accept us as humans?”. This is merely one example that characterises the emancipatory project in which many Dalits are engaged – a battle for the reclamation of human personality or personhood.

In conclusion, Ambedkar’s thinking about manus was not simply derivative of liberal Western humanism. For him, manus was the praxis of humanness – it is not merely the biological, but the sociological and the performative enactment of codes of the human. Dalit histories underscore the mobile, contextual, and transformative potential of gender, feminism, and its intensified significance in the modern politics of manuski. Dalit politics considers how to produce a new matrix of power within the category of the human itself and deepens connections between gender and the human.

Dr. Shailaja Paik is professor of History and 2024 MacArthur Fellow.

This essay is carved out from Shailaja Paik’s award-winning book The Vulgarity of Caste: Dalits, Sexuality, and Humanity in Modern India (Stanford University Press, 2022).

This article went live on April fourteenth, two thousand twenty five, at zero minutes past seven in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.