Who Counts, Who Knows, Who Decides but Caste?

While caste in India has long been understood as a hierarchical socio-economic system – a view underscored by Marxist interpretations tracing its origins to a historic division of labour – this perspective often overlooks its deeper social and epistemic dynamics. Although the Marxist account rightly highlights how occupational roles became hereditary and ideologically justified, its reduction of caste to mere economic stratification obscures a more fundamental reality: caste as an epistemic order.

In fact, within a caste-based society where specific labour is "stigmatised and degraded", the core premise of the labour theory of value loses its meaning, as some economists have noted. Ultimately, caste is a system that organises intellectual authority. It dictates who may learn, who may teach, who may interpret and who may speak with legitimacy. This controlled distribution of knowledge – what can be termed "epistemic inequality" – was not incidental to the caste system, but its central mechanism for reproducing social hierarchy.

The Rig Veda's Purusha Sukta (10.90.12) describes the divine origin of the four varnas from the body of the cosmic Purusha: the Brahmin from his mouth, the Kshatriya from his arms, the Vaishya from his thighs and the Shudra from his feet. This verse provides the oldest scriptural justification for a hierarchical social structure.

This framework was later codified into explicit law in the Manusmriti (c. 4th century CE), which states, “A Shudra is unfit to receive education… It is not necessary that the Shudra should know the laws and codes and hence need not be taught” (Manu IV-78 to 81).

This ideology of epistemic segregation finds a modern political analogue in the philosophy of Integral Humanism, propounded by Deen Dayal Upadhyaya. Contemporary Hindutva ideologues have reframed the varna system not as a hierarchy but as a non-hierarchical, occupation-based framework. However, this reframing overlooks the challenge of addressing inherent structural inequalities and discrimination.

Instead, it facilitates political mobilisation through symbolic gestures of co-option, preserving the traditional power structure while denying its oppressive nature.

Also read: Caste Census is Critical But Not Synonymous with Social Justice: Sociologist Satish Deshpande

Thus, ordered in purportedly ‘divine’ Hindu cosmology, the social order of caste in India historically rested on the strict control of learning, interpretation, textual authority and the means of knowledge production. This Brahminical supremacy, structured around the delegation of manual labour to the lower rungs of society, fundamentally shaped cognitive frameworks to assign authority and legitimacy.

As Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd argues, this structure established a sharp distinction between the privileged castes and the ‘productive castes’ – the Dalit-Bahujan communities. Their labour, which generated crucial technologies like leather processing, pottery and food production through trial and error in the struggle for survival, was systematically excluded from recognised epistemic systems.

Yet these embodied forms of innovation were systematically devalued, reflecting a persistent hierarchy that privileged ‘the knowledge of the head over that of the hand’, particularly in how histories of science and technology have been written. Such social engineering determined who could define meaning, interpret texts, assume the priesthood, write history, analyse society and be recognised as a legitimate producer of knowledge, while consigning the intellectual contributions and labour of marginalised castes to epistemic erasure.

Despite decades of democratic governance and constitutional guarantees, these hierarchies continue to shape India’s public institutions – universities, bureaucracies, political parties (including those on the left), cultural forums, archives, courts and statistical agencies.

The chronic under-representation and monopolisation of certain groups within India’s governing institutions reflect not only a political imbalance but also a deeper structure of knowledge-based segregation. Consequently, in modern India, knowledge remains disproportionately produced, interpreted and circulated by an upper-caste elite.

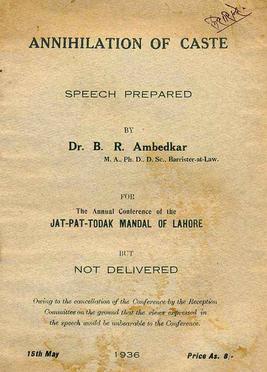

Dr B.R. Ambedkar, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Against this backdrop, the demand for a caste census has re-emerged as one of the most significant political and epistemic questions of our time. Its urgency is not simply about redistributive justice or updating affirmative action policies. Through the systematic collection of caste-based data, the census could illuminate the stark monopolisation of intellectual and cultural institutions and historically accumulated inequalities in the realm of knowledge production.

B.R. Ambedkar’s Annihilation of Caste (1936) provides one of the earliest and most incisive accounts of institutionalised epistemic segregation. His critique exposes how the authority of Hindu scriptures was leveraged to legitimise and regulate knowledge, granting Brahmins an absolute interpretive monopoly. This control allowed truth to be defined through insular Brahminical hermeneutics rather than empirical evidence or ethical reasoning. In doing so, Ambedkar demonstrates that this monopoly over meaning-making is central to sustaining the institution of caste.

Also read: Who Is Afraid of a Caste Census?

It is precisely this social architecture that sustained the monopoly of the few over knowledge, which independent India failed to dismantle. Instead, the postcolonial India’s bureaucratic, educational and cultural institutions privileged upper caste interpretive authority and perpetuated the exclusion of marginalised communities from learning. Universities became key sites for knowledge-based hierarchies.

While democratic access broadened after the 1990s with the expansion of reservations, the underlying structure of access to knowledge remained unchanged. A 2023 Nature report revealed significant underrepresentation of Adivasi and Dalit students and faculty at public institutions, including IITs and IISc.

Data from RTI and other official sources indicate that faculty reservations (7.5% for Scheduled Tribes and 15% for Dalits) remain unfilled at these institutions. Additionally, students from these communities are underrepresented right from the undergraduate level, making up to only 5% in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) courses.

The representation of these communities further dips at the PhD level. Data for PhD programmes in 2020 at five high-ranked IITs – Delhi, Bombay, Madras, Kanpur and Kharagpur – show an average of 10% representation for Dalits and 2% representation for Adivasis.

The report indicated a similar trajectory regarding the faculty representation. At the top five IITs and IISc, 98% of the professors and more than 90% of the assistant and associate professors are from the privileged castes. While the numbers in central universities are somewhat better than those in IITs, they are problematic when compared to the population share of SCs (about 16%) and STs (about 9%), especially in senior faculty positions.

These numbers are not only representative of gatekeeping exercises in hiring practices. They demonstrate a stark gap between policy and practice where institutions are systematically failing to translate the constitutional and legal commitments into epistemic inclusion.

Furthermore, low numerical representation is only part of the story. The lack of caste representation in higher education profoundly shapes the institutional climate, producing subtle yet pervasive forms of exclusion, discrimination and social isolation that influence everyday academic culture. In 2017, Scroll.in documented that Dalits constituted only about 1.12% of faculty positions across the IITs – a stark indicator of how skewed the landscape remains.

Also read: How Caste Continues to Determine Asset and Landholding Structure in Rural India

Such extreme numerical underrepresentation limits the presence of supportive mentors for students from marginalised backgrounds, constrains the diversity of perspectives that inform departmental culture and curriculum design and reinforces recruitment practices that reproduce upper-caste dominance.

While numerical data on the representation of disadvantaged communities provides an important snapshot of inequality, it cannot fully capture the deeper problem of epistemic hierarchy that the modern Indian state has reengineered through caste. A purely demographic understanding risks overlooking how caste structures what counts as knowledge, who is authorised to produce it and which cultural forms receive institutional legitimacy.

Any account of epistemic hierarchies is therefore incomplete without examining the cultural institutions that shape India’s national imagination and sustain upper caste dominance in defining its intellectual and aesthetic canon.

While the category of ‘classical arts’ is often treated as timeless, scholars such as Davesh Soneji, Lakshmi Subramanian, Amanda Weidman and Arjun Appadurai show that it is a modern construction shaped by colonial epistemologies and upper-caste anxieties over national identity. In the early twentieth century, as anti-colonial nationalism grappled with the question of what constituted an authentically ‘Indian cultural self’, the upper-caste elite – particularly Brahmins – sought to craft a refined, respectable and morally elevated heritage that could stand alongside European notions of ‘high culture’.

This impulse produced a large-scale project of ‘moral purification,’ in which art forms historically sustained by lower castes were stripped of their social contexts, sanitised and reclassified as ‘classical’. This transformation was made possible by upper-caste control over hermeneutics and meaning-making, which enabled the appropriation of subaltern cultural practices into a Sanskritised national tradition and reinforced existing epistemic hierarchies.

No artistic transformation illustrates epistemic co-option more clearly than the remaking of Bharatanatyam. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, what is known as Bharatanatyam existed as sadir, a hereditary dance form performed by women in temples and courts, from communities such as the Isai Vellalar, a backward caste group in Tamil Nadu. While the British condemned these women as immoral, Indian social reformers also targeted the sadir for abolition, condemning both the performers and the practice.

Yet, paradoxically, when the Devadasi community was criminalised through the Madras Devadasi Act, 1934, upper-caste elites – most notably Rukmini Devi Arundale – appropriated sadir and reintroduced it as Bharatanatyam. Their effort was praised for reviving and transforming Bharatanatyam by making the form more acceptable to upper-caste sensibilities.

The reimagining of sadir as Bharatanatyam involved removing erotic elements (sringara), avoiding pieces associated with temple rituals, replacing hereditary teachers with Brahmin gurus, adopting Sanskrit texts like the Natya Shastra as the authoritative canon and teaching the form to upper-caste women who embodied ‘respectability’.

Also read: India Must Not Shield Itself From International Scrutiny on Caste Discrimination

Over the following three to four decades, a deliberate effort was made to marginalise hereditary performers from cultural institutions, grant commissions and academic platforms. Their epistemic authority – the right to interpret, teach and theorise – was systematically erased.

If the late-colonial and nationalist periods established the Sanskritic imagination as the cultural core of the Indian nation, the postcolonial state subsequently institutionalised that imagination. Between the 1950s and 1980s, India built a dense network of cultural bodies intended to represent, curate, archive and distribute national culture: the Sangeet Natak Academy (1952), Sahitya Academy (1954), Lalit Kala Academy (1954), National School of Drama (1959) and Indira Gandhi National Centre for Arts (1985), among others.

While bearing a secular façade, the epistemic foundation of these institutions reproduced a deeply caste asymmetric structure. The state, instead of democratising access to cultural authority, entrenched Brahminical dominance by granting upper-caste cultural practices the status of ‘Indian tradition’ and ‘national heritage.’

The caste-coded knowledge became embedded not only in modern India’s cultural or educational institutions, but also reproduced through multiple domains, including agriculture, art, craft, jurisprudence, music and medicine – to name a few. The result is not simply social inequality but an entrenched epistemic hierarchy in which the intellectual labour of marginalised communities is disqualified as knowledge.

Plower in Pulla Caste, detail. From Indian Trades and Castes. Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons.

The political process of caste categorisation and the state's involvement in reconstructing caste identities have had serious implications for a system in controlling access to knowledge, authority over knowledge and self-representation. Its primary achievement has been to define who can produce knowledge, whose experience counts as evidence and whose existence remains unrecorded.

Also read: Need of the Hour: A Selfie Called Caste Census – India Must Confront its Truth

In independent India, the census emerged not as a mere administrative tool but as a statist imagination that constructs identities through the epistemic categories it chooses. The question, therefore, is: can the caste census, as a state epistemic project, reveal or risk reproducing that very hierarchy?

The politics of enumeration is fraught with complexity. Historically, counting communities has not only exposed patterns of injustice but also contributed to producing and stabilising them within governing categories. Anupama Rao (2009) notes that the modern state transforms social suffering into administrative visibility, turning moral injury into a bureaucratic object. Thus, enumeration can make inequality legible but also depoliticise it by translating it into numbers.

Scholars across history, political science and anthropology have long demonstrated that a census does more than count people; the very process of classification creates and fundamentally alters the traits of existing communities. Drawing a parallel between colonial and post-colonial census practices, Ram B. Bhagat (2001) contends that while the British Raj emphasised the enormous differentiations within Indian society, independent India embarked on a project of forging broader, more homogeneous communities. This state-driven, non-overlapping scheme of classification has substantially reshaped one of the primary identities of the Indian people – caste.

Thus, a caste census cannot be a mere demographic exercise; it must be an epistemic intervention. It has the potential to reveal not only deeply rooted socio-economic inequalities but also to challenge India's very conception of knowledge, practice and civilisation. In its ideal form, such a census would signify a break from the Brahmanical hermeneutical order.

However, realising this potential depends entirely on the state's capacity to overhaul the existing census system and on society's willingness to challenge the noetic monopolies that have, thus far, shaped India's modernity. Only then can it fasten India's march toward a future free from caste hierarchy and the monopolisation of knowledge production.

Swarati Sabhapandit is a research scholar. C.P. Rajendran is an adjunct professor at the National Institute of Advanced Sciences, Bengaluru.

This article went live on November twenty-ninth, two thousand twenty five, at thirty-nine minutes past seven in the evening.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.